In an early scene in Parade: Queer Acts of Love & Resistance, dozens of people clad in leather jackets, blazers and bell bottoms march toward the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. Some carry rain-battered signs with slogans like “We will not hide our love away,” while others link arms and huddle under umbrellas. The camera is situated in the midst of the crowd, and as viewers, it feels as though we’re brushing shoulders with the protestors as they pass by. Despite the dreary skies and relentless downpour, the protestors look determined, joyful.

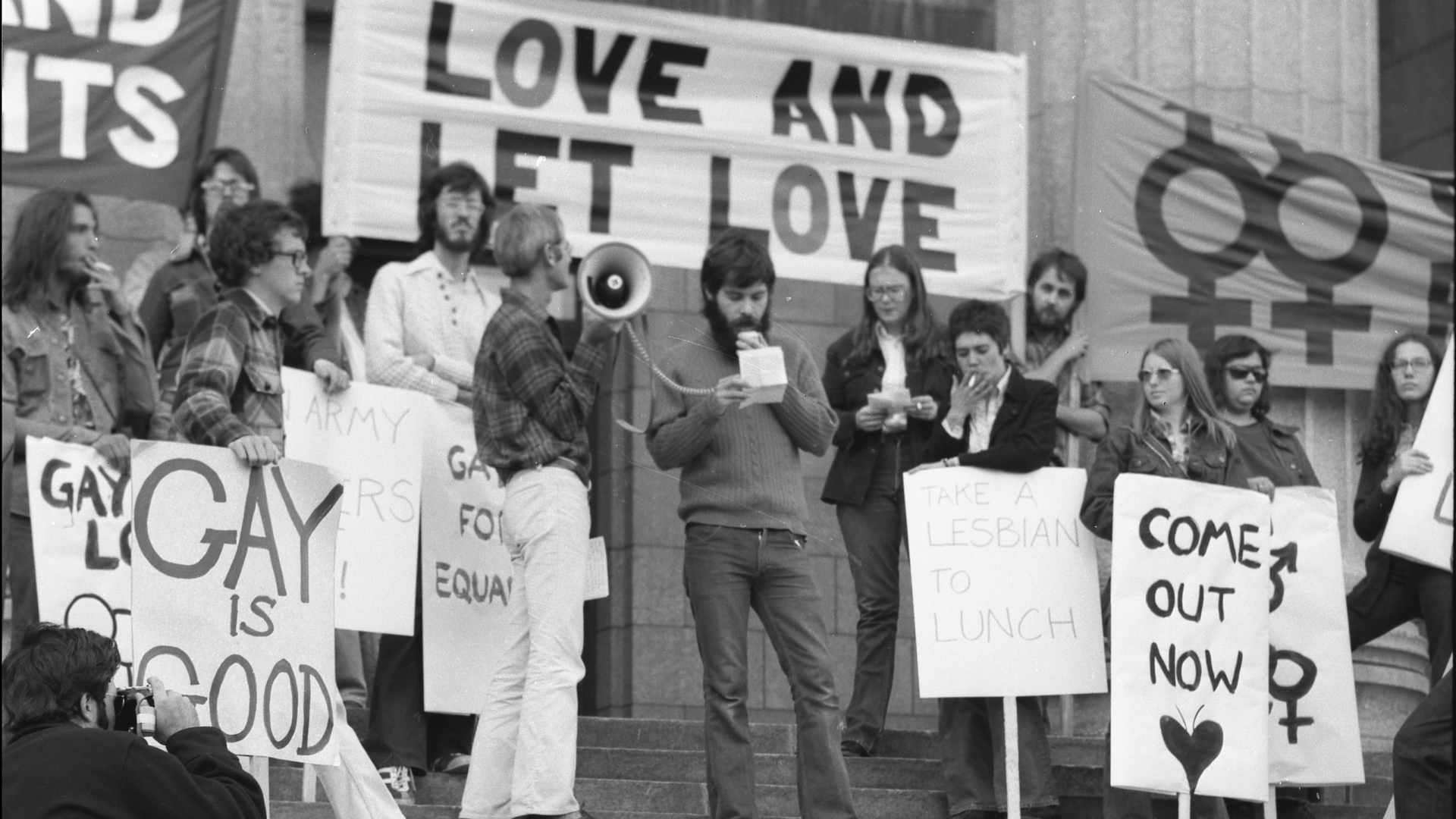

This vibrant footage of the 1971 We Demand march, Canada’s first LGBTQ2S+ mass protest, hasn’t been seen in over half a century. It had been stored in a shoebox of film reels belonging to activist Jearld Moldenhauer, who photographed many early queer demonstrations in the country. During an interview with Moldenhauer, Parade’s team discovered the existence of the footage and, with his permission, digitized it. The footage brings colour to a milestone in the history of queer activism in Canada, capturing the protest on grainy, nostalgic Super 8 film. It shines as an exemplar of the kind of archival work that powers the new documentary Parade, directed by Winnipeg filmmaker Noam Gonick and produced by Toronto’s Justine Pimlott.

Parade is set to premiere on Thursday at the opening night of Toronto’s Hot Docs Festival, the largest documentary festival in North America. The film recounts key moments in the fight for LGBTQ2S+ rights in Canada, with chapters dedicated to events like the 1981 police raids on bathhouses in Toronto and the introduction of the term “Two-Spirit” in Winnipeg in 1990. In lieu of an omniscient narrator, Parade is driven by elders and activists recounting their experiences. This personal testimony is paired with archival footage that captures the power of communal experience and collective action. The gorgeous colour footage of protests is deeply moving: lesbians, trans folks and gay men march shoulder to shoulder, filling Toronto streets that will be recognizable to many local viewers. It’s an approach to storytelling that radically centres the agency of the people who participated in, bore witness to and documented turning points in the nation’s burgeoning queer movement.

Parade emerges at a time of heightened interest in queer and trans history. In recent years, queer libraries and walking tours have blossomed across the country. Award-winning podcasts and films have delved into Canadian LGBTQ2S+ history. The viral street-interview game show Gaydar—in which celebrity guests and everyday passersby answer questions about queer culture and history—has garnered hundreds of thousands of followers on TikTok. Among many queer and trans people, there seems to be a renewed desire to look to the past for lessons to tackle the growth of anti-LGBTQ2S+ movements and legislation across the world today.

Parade’s filmmakers are well aware of the documentary’s educational role in this context. Gonick, whose queer bizarro sci-fi flick Hey, Happy! premiered at Sundance in 2001, says Parade serves as a tool kit for the protection of queer rights. “The film really spells out the steps that were taken: the organizing, the protests, what the issues were, how people rose to the challenge in various provinces over the decades to fight back and to win these gains,” he says. Parade takes on the heavy and ambitious responsibility of trying to restore the community’s collective memory of how rights had been fought for and achieved by a generation of activists across Canada.

“Love Thy Neighbour.” Toronto Gay Pride March, 1973. Super8 still. Credit: Courtesy of Jearld Moldenhauer

“If I took this mask off, I would lose my job.” Lesbians march incognito, Toronto, 1973. Credit: Jearld Moldenhauer

There are, indeed, harrowing parallels between the events documented in Parade and contemporary attacks on LGBTQ2S+ rights. As the film unpacks the experience of Jeanine Maes, who was institutionalized in a Montreal psychiatric hospital in 1962 to “cure” her of the “mental illness” of homosexuality, there are echoes of anti-trans talking points and the medicalization of gender nonconformity today. Debates about the gay age of consent in the ’70s call to mind recent policies limiting trans youth’s ability to make decisions about their own bodies. On a more hopeful note, the story of how American anti-gay crusader Anita Bryant’s 1978 visits to Canadian cities galvanized and united LGBTQ2S+ activists mirrors the experiences of local communities who came together in counter-protests against anti-trans groups that have targeted sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) educational resources in schools over the past few years.

But where Parade’s practicality truly shines is not in showing the nitty-gritty of how protests were organized and policy change was enacted through collective action. Rather, it’s in the film’s nuanced and caring approach to unpacking a history that has long been invisibilized and hidden away. The film honours the memory work—of remembering, documenting and sharing history— done by many queer elders and activists. Its community-centred approach to understanding, preserving and presenting LGBTQ2S+ archives provides a blueprint for how we can better honour and protect stories that may otherwise disappear.

Finding and accessing queer historical records is often a difficult feat. Part of the problem is that many institutional archives, like those owned by universities and governments, have long excluded queer life and culture, or presented a view focused on the experiences of white cis gay men. Many queer archives are kept within the community, by activists and witnesses who have developed personal collections by gathering photographs, film and ephemera over the decades.

The imagery and footage in Parade comes not only from institutions like the ArQuives, the only national LGBTQ2S+ archives in Canada, but from the basements and homes of activists. Producer Justine Pimlott says that even as greater societal acceptance has made it possible for more queer and trans people to be out, locating these historical materials was a challenge. “The archives become the new thing in the closet, instead of the people,” she says.

Two-Spirit delegation at Toronto Pride, 1992. Credit: Courtesy of David Troster, Ontario Archives

Jonas Ma, Gay Asians of Toronto Credit: Norman Taylor, courtesy of ArQuives

Archives are fragile. This is often true of their physical form—they exist in different formats that may need to be digitized and stored in unique ways—but also of what they represent. Pimlott says that while Parade features activists sharing moments of happiness and victory, there are also stories of struggle, violence, pain and trauma. “Going [down] that rabbit hole isn’t always pleasant,” says Pimlott. “It evokes a lot of difficulty, sometimes.”

Parade’s team approached the archival process by drawing heavily on its members’ existing relationships with communities, activists and archivists. Many of the filmmakers have been friends for years with people featured in the film, or were involved in activism and participated themselves in some of the events depicted. That foundation of trust and those roots in the community supported other activists in sharing their own intimate and honest first-hand accounts. Gonick says the team even became a conduit for film about LGBTQ2S+ life in Canada; even if footage didn’t make the final cut, it was passed on to the ArQuives for preservation.

One of the most poignant moments of the film comes in the chapter about the AIDS crisis and the loss of a generation of queer activists. In the film, grief worker Yvette Perreault describes caring for young gay men as they died of AIDS. She talks about losing all of the people she used to go dancing with when she first came out. “Sometimes I would go to Pride, and it would feel like the universe was Swiss cheese with holes in it—like, I would see the people who weren’t there,” recounts Perreault. “[For] maybe three years, I couldn’t go to Pride events ’cause I would only see the ghosts.”

Pimlott recounts the deep impact that interview had on the film crew. “When Yvette was telling that story, there wasn’t a dry eye in that studio,” she says. “I felt like that was actually a very powerful and healthy experience—because we do need to be able to come together and also grieve, and dance.”

Parade honours several key activists who have passed away, like Lesbian Organization of Toronto co-founder Chris Bearchell and journalist Gerald Hannon. We see their photographs, hear their voices from archival recordings and watch them celebrate on the streets as other activists recount their legacy. The film keenly portrays this sense of communal loss, celebrating figures whose names have long been omitted from history books. It is also a call to arms to reach out to and learn from the queer elders who are still with us, and to preserve stories that are gradually disappearing. Parade invites us to see the ghosts, and challenges us not to look away.

Parade premieres at Hot Docs in Toronto on April 24 with showings through May 3.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra