“You think you can change everything” is an accusation thrown at the narrator in the early pages of I Remember Lights, a gay coming-of-age story set in 1960s and 1970s Montreal. The accusation does not come from a scornful straight person, but rather from his lover, another gay man. We are in 1967 Montreal, just as the city is preparing to host Expo 67, and our unnamed narrator, a nineteen-year-old transplant from New Brunswick, is learning to navigate the world as the queer person he has recently understood himself to be. It is a world in which same-sex acts are illegal—it wasn’t until 1969 that consensual gay sex in private became legalized in Canada. Unlike his lover Honoré, who is happy to pick up at gay bars but plans to marry a woman according to his family’s wishes, the narrator is determined never to engage in a sham heterosexual pairing. His desire to, if not “change everything,” then at least live his life as honestly as he can despite rampant homophobia, provides the thrumming undercurrent of the novel. In response to Honoré’s scoffing, the narrator, younger and poorer and less experienced than the other man, nevertheless boldly asserts: “I want men and I want love. I want both.”

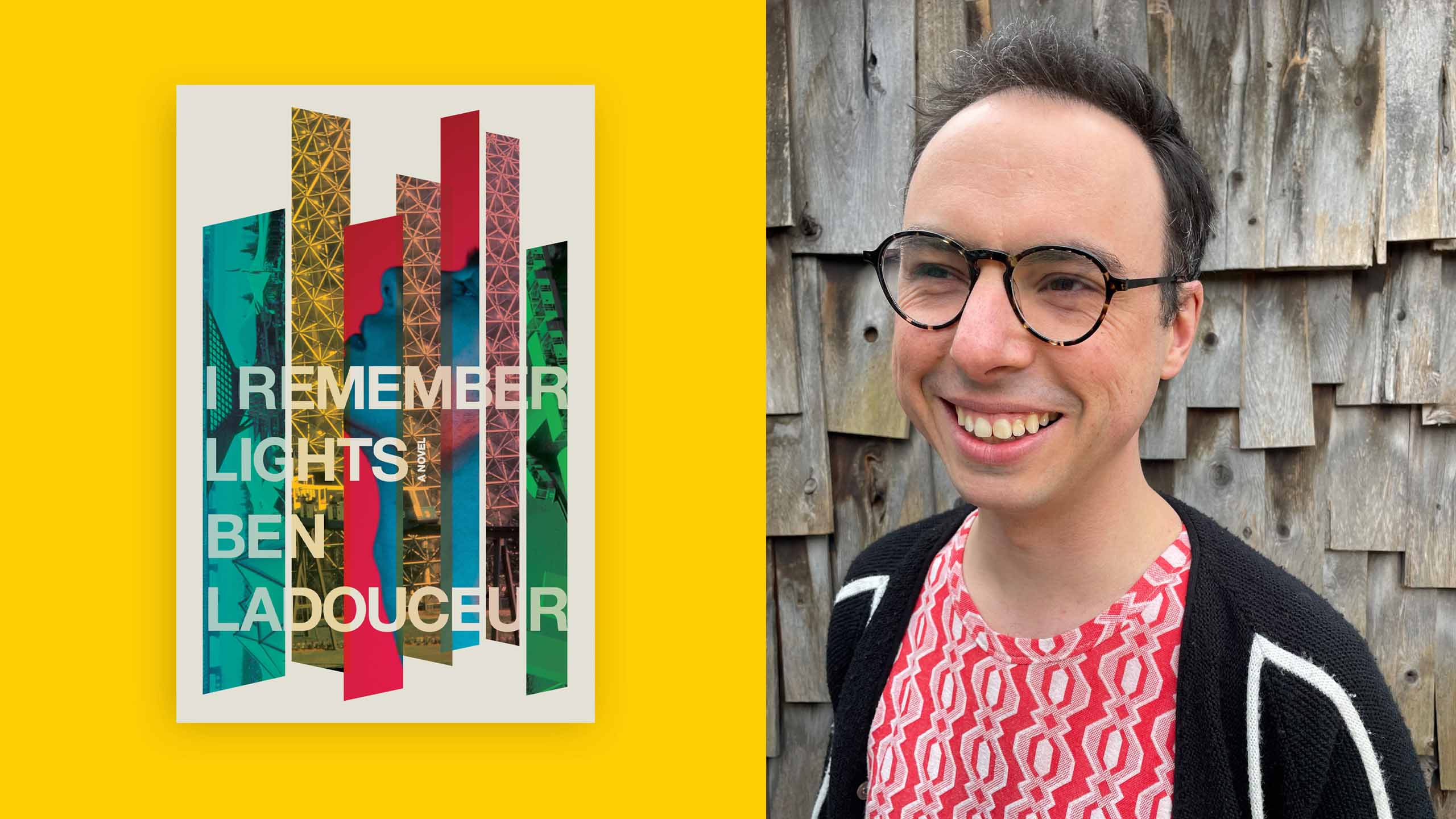

I Remember Lights is the debut novel by award-winning Ottawa-based poet Ben Ladouceur (Otter, Mad Long Emotion). Divided into three distinct sections, it follows its narrator as he discovers the gay bars, cruising grounds, rental apartments and odd jobs of 1967 Montreal; succumbs to his first big love affair; and later, in 1977, gets violently arrested alongside 200 other men in the infamous police raid of Truxx Bar. The first section of the novel switches back and forth between the growing hopefulness of the narrator’s burgeoning queer life, and the fateful night of the mass arrest ten years later. The second section, its most energetic, covers the heady summer of Expo 67, during which Montreal’s newly formed islands become a campy international playground for tourists, and the narrator falls in love for the first time. The third section returns to a rhythmic back-and-forth between 1967 and 1977: in the former, the narrator follows his love Tristan to his native Britain with mixed results, while in the latter, he endures the police violence and humiliation of the bar raid, and emerges into its aftermath. The novel is thoughtful and well researched; for the harrowing section about the Truxx arrests, Ladouceur interviewed victims of the police raid, who had not previously shared their stories publicly.

Ladouceur draws a detailed portrait of urban life in 1960s and 1970s Montreal. The geography of the city in that period is recognizable to those of us currently familiar with it, and yet slightly askew: in I Remember Lights, Île Sainte-Hélène and Île Notre-Dame are newly formed from earth dug up elsewhere and home to glitzy nation-themed pavilions full of tourists and international staff; Habitat 67 is a fascinating new architectural marvel full of hip house parties; and the city’s gay nightlife is much more clandestine, and clustered around Peel and Stanley downtown, rather than farther east on Sainte-Catherine where the Gay Village is now. But certain things stay the same: Mount Royal has always been a cruising ground, Anglophones from out of province have always flocked to the Mile End and are slow to learn French and the Montreal police have always been happy to violently arrest marginalized populations and protestors en masse without provocation.

I Remember Lights provides reminders not only of Montreal’s changing geography but also of the charged and changing status of homosexuality over the decades. Throughout the novel, the narrator and the queer people he encounters (mostly men, with the odd lesbian thrown in), all struggle with different iterations of the same questions: What is the cost of living a gay life? How much are they willing or able to hide themselves in order to get by? Honoré, who lives a life of closeted material comfort, sneers at the narrator’s assertion that he will continue to love men, and do so openly. Tristan, the narrator’s first love, the most exuberant gay person the narrator has ever met, becomes much more fearful of being outed when he is forced to move back to Britain in the book’s third section. Adopting a nomadic life as a hostel caretaker, Tristan sheds much of his queer levity, and, afraid of losing his job, becomes increasingly concerned with fitting in with his straight male co-workers. Étienne, a Black gay Parisian man who becomes the narrator’s roommate and friend, is somewhat relaxed about his queerness, happily leaving his gay porn magazines in plain view in their apartment and always willing to share them with the narrator. At the same time, he is resentful of the restrictiveness of social norms, and also has to contend with racism from employers. He is forced to straighten his hair once he gets a job working the Expo; he uses conk, a noxious, painful paste made of eggs, potatoes, and drain cleaner. Étienne’s Blackness isn’t explored much further than this in the novel, especially as it relates to his queerness, other than some mentions of James Baldwin—a missed opportunity in a book that mostly describes a white gay world. These three men, and others with whom the narrator has briefer encounters in cruising grounds or bathhouses, inspire and influence him: he welcomes some aspects of their philosophies and rejects others. In this way, he begins to decide what kind of life he wants to live.

In the 1967 sections of the book, the narrator is frequently reminded by straight people that his queerness is visible and that it is either worrisome or outright disgusting. He receives unsolicited prayers from Michel, the delivery driver he works for, and advice from Maria, the woman he rents a room from, who tells him that he needs to “smarten up” soon, that he will need to become a husband and that “your wife cannot know.” Later on, riding the new Metro line to the Expo, he feels hemmed in by this need to be discreet, to never say out loud how he feels or what is really going on in his life: “I felt the earth all around me, clumpy and stable, unseen and unfathomably heavy.” At the same time, he is galvanized by the islands and buildings being erected for the Expo, the way the land is being dug up and rearranged into new shapes. He feels a surge of confidence: “Things were becoming possible that hadn’t been possible previously.” He does not, he decides, have to live the miserable, secretive life that Maria, Honoré and others consign him to. Later on, after a vicious verbal attack from Maria’s adult daughter, who accuses the narrator of being a child molester because he’s gay, the narrator is able to find comfort with Tristan and in the campy energy of Expo. He is able to weather the straight vitriol in large part because he has found love and companionship among other queer people.

The narrator’s love affair with Tristan is a highlight of the book, drawn in poetic detail. At one point, as the romantic and sexual tension between the two men nears its peak, the narrator becomes fascinated by Tristan’s hands, thrilled by his decision to wear nail polish to go out in public: “I thought he looked excellent and knew immediately that the next time I jerked off, I would think of his hands again, their knuckles and polish—hairy knuckles, green polish.” Their relationship is fast and passionate, as many first-time queer relationships can be, and tragically cut short by Tristan losing his Expo job when his boss finds out he has epilepsy. Without a work visa, Tristan has to move back to Britain. Almost as soon as he’s found him, the narrator is set to lose this person, a person who, as he puts it, “made me less mysterious to myself.” Unlike some of the straight couples they know who met at Expo, they can’t get married in order to stay in the same place. Eventually, when the narrator manages to fly to England to resume the relationship, the tone shifts from the highs of infatuation to the lows of worry and stress. Rural England is not the same as downtown Montreal—there are no gay bars in which to seek respite, no other gay people to befriend and without these refuges, the couple is doomed to a life of hiding, a life that the narrator has already decided he cannot accept.

Later, at the time of the 1977 Truxx raid, the narrator, living in Montreal once again, has maintained his queer life as he said he would, without needing to resort to straight disguises like marriage. The rhythm of his days, his relative freedom to frequent bathhouses and to go dancing at bars like Truxx, is harshly interrupted by the police raid. Thanks to the interviews he conducted with survivors, Ladouceur is able to describe the raid in harrowing, enraging detail. For the first time, caged with the other men, subject to police humiliation and violation, the narrator experiences a feeling of hatred toward the other queers, and toward himself. Witnessing another man’s distressed glare: “I hated him back, perhaps because of what I had seen him go through, and perhaps because he knew I had gone through it too.” And yet, though the tone is sombre, we do not get the sense that the experience of violent repression will change the narrator’s decision to live a queer life. Returning home after the hellish ordeal, the narrator comforts his dog, aptly named Dorothy, saying, “It’s okay. Settle down. It’s okay.” The police violence will not, we understand, stop gay people from existing, fucking, dancing, befriending or loving each other.

Though the men in the bar are subjected to police violence simply for being queer and hanging out at a known gay establishment, Ladouceur shows us that in 1977, there was more willingness than in 1967 to be queer in public—when the arrestees are finally freed from jail, there is a crowd of people to welcome them outside, shouting and waving signs that say “Gay is OK” and “Gay Is Not Evil.” In fact, the Truxx raid led to a wave of protests and queer organizing in Montreal; later that year, queer activists successfully lobbied the provincial Parti Québécois government to amend the Quebec Human Rights Charter to include sexual orientation as a prohibited form of discrimination, making Quebec the first Canadian province to do so.

This aftermath is not in the scope of I Remember Lights, which concludes with the raid, but the knowledge of the legal victory that followed serves as a bolster for the book’s muted yet ambiguously hopeful ending. Things may not get better in a linear fashion, but queer people can organize together and fight back against state and societal violence and erasure. I Remember Lights serves as an important reminder to us now, as the rights of trans people and immigrants, and many other groups, are increasingly under attack, that gathering and fighting together, though it may not change everything, is nevertheless of crucial importance.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra