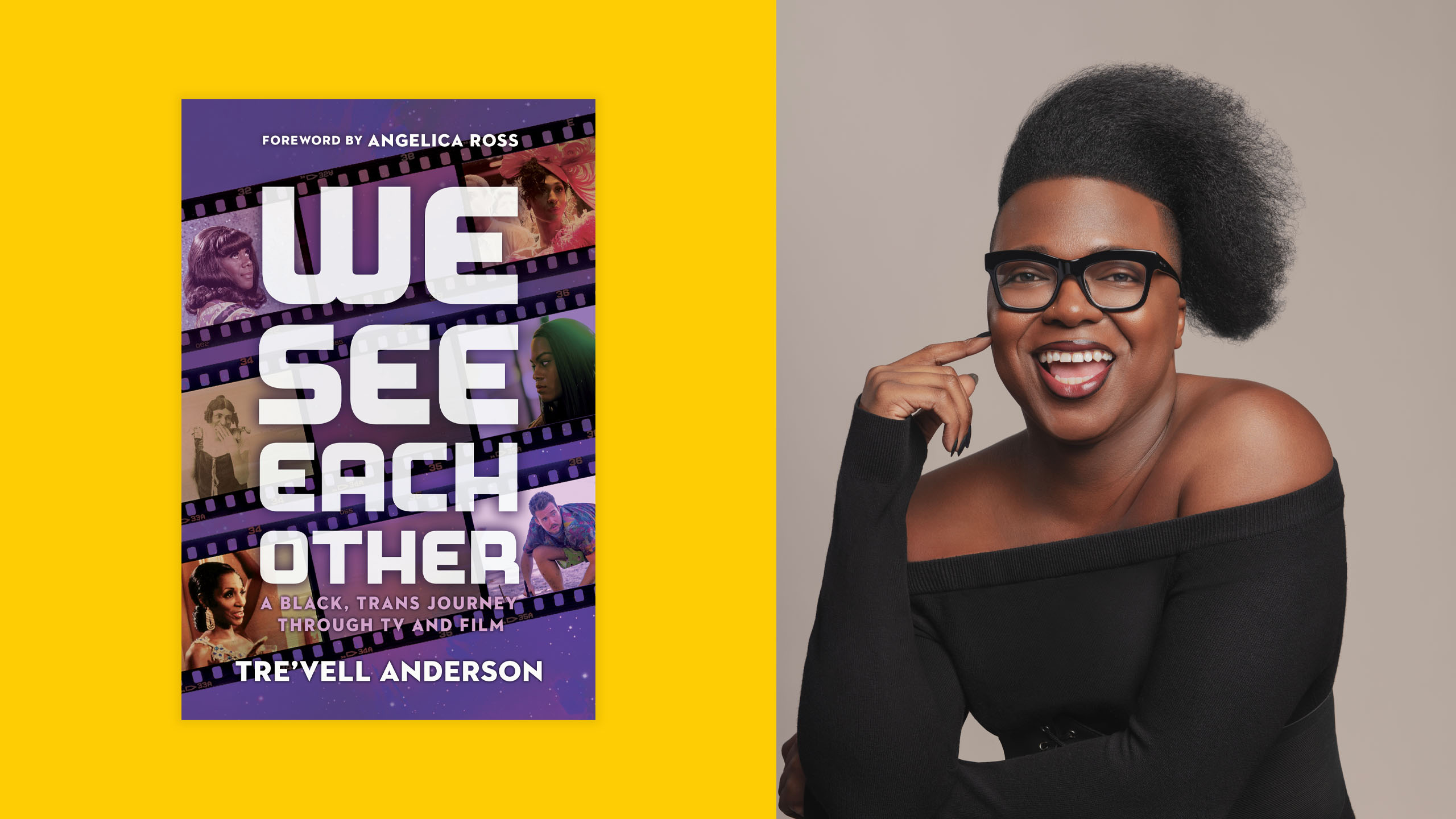

“I don’t remember exactly when I was taught to hate myself.” From the opening line of award-winning journalist Tre’vell Anderson’s first book, We See Each Other: A Black, Trans Journey Through TV and Film, they grab your attention and signal that this history of trans, non-binary and gender-nonconforming representation in popular culture will be a beguiling mix of biography, history and analysis. Anderson’s unflinching gaze and personal insights alight upon everything from classic films such as Some Like It Hot and Psycho to TV shows like Pose and RuPaul’s Drag Race to stories of real trans folks erased from the historical record.

Formerly editor at large at Xtra and director of culture and entertainment at Out, Anderson, a native of Charleston, South Carolina, began their career as a film writer at the L.A. Times. Currently the host of two podcasts, Crooked Media’s What A Day and Maximum Fun’s FANTI, Anderson is also a regional director and past president of the National Association of Black Journalists of Los Angeles. Their next book, Historically Black Phrases, is coming out later this year.

In this excerpt from Chapter 1 of We See Each Other, Anderson examines the complicated legacy of Tyler Perry and the cultural juggernaut that is Perry’s drag alter ego Madea.

I, likely, was somebody’s Madea in a past life. Yes, the brash, Glock-toting matriarch on whose back the Tyler Perry empire is built. There’s just something about a woman who allegedly shot Tupac and only prays to God when writing a check that speaks to my core.

My granny introduced me to Madea. I like to think that she had heard from her holy-roller friends about this guy down in Atlanta who had been doing these stage plays that, while rooted in the Bible, had all the drama and energy of a soap opera. On the strength of their recommendation, when the bootleg man who sold DVDs under that highway bypass mentioned he had a filmed copy of the Madea play I Can Do Bad All by Myself, she quickly passed him a folded five-dollar bill.

In reality, I don’t know if she knew what she was doing by copping this disc. It was the early 2000s and going to the movie theater, let alone a stage play, was a luxury and a usually too-hefty-for-us expense that could be eliminated by waiting a couple days post-release. The bootleg men—because the ones we always bought from were men, it seems—were quick with it, honey. You only hoped that the copy you got didn’t have folks walking across the damn picture or too many IRL audience members whose collective laughter ruined the audio quality. No shade, you wanted the copy that was likely filmed at an early showing attended only by folks who got senior discounts.

I Can Do Bad All by Myself is about a gaggle of folks living in Madea’s house—Vianne, Madea’s granddaughter, who just divorced her abusive stockbroker husband; Bobby, an easy-on- the-eyes chocolate drop who just got out of jail after serving twelve years for drug possession; and Madea’s great-grand-daughter, fourteen-year-old Keisha, who resents her mother, Maylee (Vianne’s sister). The play is about broken relationships, sexual assault, faith, and forgiveness. Throughout the production, different characters break into song: original gospel ditties and renditions of classic hymns. My granny was hooked.

I wasn’t immediately enthralled. Though as a baby church queen at the time, I loved most of the singing—especially a post–Kirk Franklin and the Family, pre–“Take Me to the King” Tamela Mann—the melodrama was just too damn much for me. The traumatic twists and turns of the narrative, now a staple of most Perry productions, were so campy and hyperbolic that I couldn’t truly get into the world that was being built before my eyes. But when I tell you that my whole family got a good laugh out of it!

Sometime later, my mom, Melliony, got her hands on a bootleg of Perry’s Diary of a Mad Black Woman. Maybe she got it from someone stopping through the barbershop or beauty salon, maybe it was a grocery store parking lot. About an upper-class couple who, from the outside looking in, are living the dream, the play follows the deterioration of Helen and Charles’s marriage. When Helen discovers that Charles is cheating on her with her best friend, her mother, Myrtle (Tamela Mann), and Madea come over to cheer her up and give a little advice. Myrtle is the Bible-thumper vehemently against any revenge plot Madea is cooking up. She only endorses prayer and forgiveness as appropriate responses for Helen. Madea, on the other hand, is the type to shoot first and ask questions later. It’s at this point in the Madea Cinematic Universe that I fell in love.

My granny, Dorothy, was a local celebrity of sorts, having toured throughout the South as one of the Voices of Thunder, the gospel singing group she had with her siblings. As they all got up in age, the group unofficially disbanded, only coming together, usually, to perform at revivals that my granny staged at her church. God’s Tabernacle was officially a nondenominational church, but it gave very much Baptist and Pentecostal every chance it could. My granny also had a radio show on which she’d deliver a weekly sermon over AM airwaves. I’d occasionally join her, reading out Bible verses. Philippians 4:13 was a favorite, and remains one of the few verses I can recite from memory. I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.

Folks just assumed I was going to follow in Granny’s path and become a minister. I will say, I do remember my granny hosting a youth revival featuring a slate of young ministers. I seem to recall someone on the program that was easily in her thirties. I wasn’t even a teen, I don’t think. And if I was, I was barely. I’m not gonna toot my own horn—toot, toot—but I did have a lil’ knack for getting the saints up out their seats, all of which I learned from my granny.

Around that same time, I want to say, I began forming questions about the stories in the Bible I’d come to know so well. And as I learned more about my granny’s own journey to the pulpit, I realized the ways in which the Bible has been, historically, used to justify the oppression of various communities. The slave masters did it. Men preachers who often lead their flocks to ruin did it. The religious right is currently doing it.

This discovery began my retreat from God and church, in a formal sense, though it was a slow drip. My intro to Madea came around the same time, and to see this character who poked fun at and reinterpreted the Bible for her heathen intentions was extremely entertaining. Hell, it was edifying for a baby queer who knew enough about themselves since age four to know they weren’t ending up in nobody’s pulpit long-term.

There’s a particular scene in Diary of a Mad Black Woman, the play, that I won’t ever forget. As a retort to Myrtle’s hope that her daughter will just pray and let God handle her situation, Perry as Madea riffs off of a Bible verse Mann (as Myrtle) has quoted. “Hold your peace and let the Lord fight your battle.” As Madea repeats the Bible verse a few times, she subtly slides her hand into her purse. As she says the verse one last time, she brandishes her gun: “Hold your piece …” The audience erupts in laughter. For added measure, after sliding her gun back in her purse, Madea offers a verse of her own. “Blessed are the peacemakers,” she says. Then she pulls the gun back out: “Blessed are the piece makers, Smith and Wesson.” I had never laughed so hard; hell, it still tickles me to this day.

From there on out, my family and I bought Tyler Perry’s plays whenever they came out—even the ones from the late 2010s that trafficked in social-media stars and weren’t as funny as their predecessors. And when Madea started getting the big-screen treatment, my family was first in line at the movies, usually on Sunday evenings, I think, starting with 2005’s film version of Diary of a Mad Black Woman, which starred the legendary Kimberly Elise. Even when the films jumped the shark—cough, Madea’s Witness Protection, cough—we were there, helping Perry build his empire. And as Madea’s -isms, like “Hallelujer!” and “I ain’t scared of the po-po. Call the po-po, hoe!” gained popular traction, they were already featured in my lexicon. Up until my granny died in 2016, every time I came home for the holidays, we’d cue up a few Tyler Perry movies and plays, like it was the old times.

Tyler Perry, and particularly his character of Madea, was—and is—embedded in my life. Even as I write this, I own too many of his plays on iTunes, and watch them regularly enough to not be ashamed. But in college, around the release of 2012’s not-as-funny and puzzlingly absurd Madea’s Witness Protection and amid my coursework in sociology and Black feminist theory, I began to make a connection between the types of images we see on-screen and the ways people, in real life, treat each other—and the ways we treat ourselves.

This history of trans visibility is one that forces us to contend with conceptions of identity that don’t reflect our contemporary understanding. By that I mean that characters played by men cross-dressing as women, like Madea, are as integral to our discourse as characters played by men, women, or otherly gendered folks that are expressly identified as trans or gender-expansive. So let’s start there.

[…]

When I detail my relationships to various media, I try to make space for the complex and complicado. It’d be disingenuous otherwise to not recognize that we, as trans people, can both be entertained by these characters who were foundational in our media diets and question the ways that they are complicit in the ongoing acts of violence we experience.

I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to not laugh at the absurdity and comedic brilliance that is Madea, particularly in those early plays. The character and Perry’s portrayal are deeply connected to so many aspects of my life that I hold dear—my granny, being a Southern Belle, my love-hate relationship with the Black church, the complexities of Black Hollywood. And yet still, it’s important that we all acknowledge how these characters y’all see as just comedic fodder manifest off-screen as sites of trauma, how the ways we laugh at them are connected to how y’all laugh at us trans people for even attempting to live as our authentic selves.

I can say that these characters and the jokes made at their expense become emotional and physical violence because I’ve been on the receiving end of them. Hell, I’ve internalized many of them so much that I throw them at myself before the world gets a chance to. It’s what plays on a loop in my mind when I’m trying on “women’s clothes” in a fitting room. It’s what I think of, quite instinctually unfortunately, right before I leave my home each day, my reminder to arm myself for what may come, said and unsaid.

These tropes we’ve come to know as commonplace in film and television, and onstage, aren’t us, though we’re being treated as if they are.

This adapted excerpt is from the book We See Each Other by Tre’vell Anderson. Copyright © 2023 by Tre’vell Anderson. Reprinted with permission of Andscape Books. All rights reserved.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra