In his 2005 Pulitzer-winning play, Doubt: A Parable, John Patrick Shanley offers a spare and searing investigation into truth and suspicion and just how profoundly uncomfortable we are with everything in between.

“When I read this script, long before I ever had the chance to see it, I knew it was essential Pacific Theatre material,” writes artistic director Ron Reed in his program notes. “I also knew it was one of the greatest scripts I had ever read.”

Pacific Theatre’s goal — “to delight, provoke, and stimulate dialogue by producing theatre that rigorously explores the spiritual aspects of human experience” — is fully realized in Shanley’s script. At its crux is a question of alleged sexual abuse in a Catholic elementary school in 1964.

In 2012, however, sexual abuse in the Catholic Church is a foregone conclusion, isn’t it? It’s more apt to be the stuff of standup comedy than an award-winning script and screenplay.

But at its core, Doubt probes the consequences of blind faith when such significant aspersions are cast. And much damage has been done in the name of blind faith.

We’ve seen the hateful placards, printed with unwavering conviction, proclaiming “God hates fags.” And we’ve watched the angry faces — apoplectic with certitude — accuse us of being, at best, immoral and, at worst, nothing less than predatory.

In a 2005 PBS interview, Shanley explained, “I was very interested in having a powerful character chasing down a course of action that was going to do a lot of harm if she was wrong.”

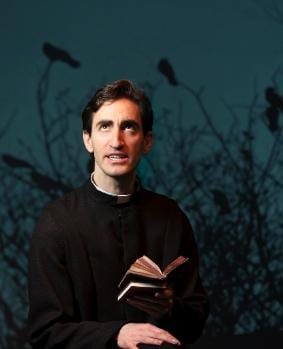

Sister Aloysius, the fear-inducing principal of St Nicholas School, is that powerful character. And what she’s chasing is her certainty that the parish priest, Father Flynn, has initiated an inappropriate relationship with a troubled altar boy. The harm she may cause is far-reaching and includes not only the priest’s destruction, but also her own removal from the Order, as well as the boy’s expulsion, tantamount to ending his education entirely.

In a captivatingly restrained performance by Erla Faye Forsyth, we see the depth of Sister Aloysius’s humanity as well as the flame that ignites her unwavering commitment.

“There’s a very strong spiritual aspect — mystical almost — that’s come into it,” Forsythe says. “I don’t think it’s just her seeing it. I think she believes God told her. And that’s what she has to hold on to.”

Early in the script, our sympathies are not with Sister Aloysius. Her initial recriminations against Father Flynn echo McCarthyism.

But the priest’s equivocal response to her charge smacks of deflection and the certainty of our sympathies shifts.

“From one paragraph to the next I would think, ‘He is a terrible man and she’s a hero to protect these children,’” says Reed, describing his first impression of the script. “Then a moment later I would think, ‘No, he’s falsely accused, his life’s being ripped away from him, and she’s on a witch hunt.’ I found that so invigorating, so thrilling. That’s the experience I’m in charge of giving the audience. Not that they never know, but from moment to moment it changes.”

This is Shanley’s genius — leaving us unsteady on our pins and unsettled in our resolution, arguing that doubt is not only the most humane condition, but also the most sacred.

In the preface to the published script he writes, “You may come out of my play uncertain. You may want to be sure. Look down at that feeling. We’ve got to learn to live with a full measure of uncertainty. There is no last word. That’s the silence under the chatter of our time.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra