Some trans kids know they are trans right away; other trans youth don’t fully arrive at the language to describe their experience of gender until they are adults. Joris Bas Backer and I were both in the second category, and we’ve both made it our goal to write about queer teens whose process of self-discovery unfolds more slowly. Backer is a cartoonist, illustrator and father who writes and publishes in multiple languages. After an international childhood that included stays in the Hague, Bucharest, New York and the Dutch town of Oegstgeest, he landed in Berlin, where he now lives and works.

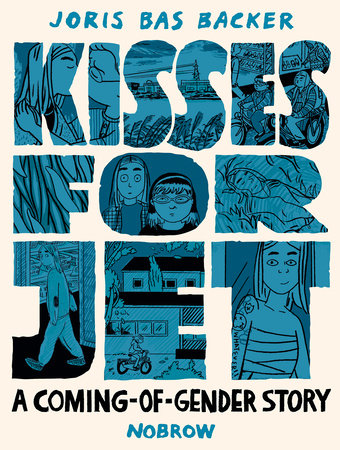

Credit: Courtesy Nobrow

His queer, coming-of-age graphic novel, Kisses for Jet, was released in German in 2020, and is being released in English this month from Nobrow Press. Set in 1999, Kisses for Jet follows a gender-questioning teenager who has to move temporarily into the dorms at an international boarding school in Holland while their parents focus on work. In the uneasy proximity of many gossipy and noisy classmates, Jet begins, fumblingly, to explore their gender and sexuality, with no roles models and few sources of information on queer identities. Luckily, Jet is able to escape into a world of art and music with their friend Sasha, who shares a love of Kurt Cobain and mild rebellion. It is through conversations with Sasha that Jet begins to realize they might, in fact, be trans.

I first became aware of Backer’s work when we both had stories published in the comics anthology How to Wait (2019), a collection of stories, edited by Sage Persing, from trans and non-binary authors on the periods of enforced waiting that are inevitably included in all transition processes. I was very happy to talk with Backer about the process of writing Kisses for Jet, what drew him to comics as a medium and our shared love of libraries. We spoke over an international call last winter.

For me, writing is a hugely useful exercise in figuring out how to actually express what gender means to me and how I relate to it. Writing Gender Queer was definitely an extension of my process of self-discovery and of coming out. I’m curious about where you were in your transition when you started writing Kisses for Jet. Where did this book fit into your own self-growth?

Identity is a really big theme of my work. I grew up juggling different identities because I grew up internationally, and I always had people from a lot of different cultures in my classes, and was relearning social behaviour in each new country. When I was 11, I moved back to Holland, and it was a really difficult move because I couldn’t just be “the Dutch person” that I had always been in other countries. All of a sudden, people were mirroring back to me that I wasn’t Dutch. And it was really strange. But then I switched into an international school, and it wasn’t a problem anymore, but I just became really fascinated about it.

So I was going to write a book about my teenage years, the two years I spent at a boarding house in the international school. And it was going to be about identity, about how these people from different countries relate to one another and the languages they speak. I decided that one of my characters was trans, and then I had to research everything I could about transitioning in order to be able to write this character well, and it was a good excuse because I wasn’t really in a situation where I felt I could be open about the fact I was questioning my own identity. I was in a relationship and we had a small kid and I knew it would kind of risk that family if I were to come out. You know, it just becomes complicated. So it wasn’t something I felt like experimenting with openly. And so if someone asked why I was reading about transitioning, I would say that I’m researching this character. And then I would read books and watch films and it was really comfortable because it was always about this other character. But then there was this moment when I just read certain lines in a book by a Dutch writer and it was just like—it was just so apparent that it was about me that it really hit me. Wow. I’m horrible at keeping secrets. I had two bad weeks of denying it. After that, I just started telling the people who needed to know. It was amazing.

I know you wrote a short comic called The Break Out earlier, which is also about being at an international boarding school and feeling very claustrophobic in the company of these other teenagers. And I know that some of those same themes ended up in Kisses for Jet. So was this research done between when you wrote The Break Out and Kisses for Jet?

The Break Out is the early version of Kisses for Jet, before I knew that I was working on a book. And also before I knew I was trans.

Gender Queer also has an earlier online version. I knew I was coming out, but I didn’t know I was writing a book, so I relate to that.

I think there’s a process that goes into, like, having the guts to work on a big book. To dare to say that, “I consider myself important, I take myself seriously as an artist and I’m going to do that thing that I really want to do and make a book, and I think I can.”

Kisses for Jet took a long time of going through all the different versions of writing one short story, and then deciding the short story would become a book, going back and changing the style, and then changing the structure, and then discovering I was trans, and then going back and rewriting. It was a lot of that.

There’s a real back-and-forth between reality and fiction in the book—like the book was a catalyst that allowed me to discover myself. As I discovered myself, I went back and put it in the book. But it’s also what made me turn the book into fiction because it was a lot more of a memoir in the beginning, and I needed it to be fiction. To tell that story.

That’s wonderful. Sometimes being a memoir author will actually push me to take real steps to move my life forward in order to make art about it. It’s as if art and life are both pushing each other—like they’re two feet on bicycle pedals, life pushing forward the work, and the work pushing life.

Yeah, yeah. It’s a back-and-forth. There’s like a tide system to it.

Absolutely. So, what pronouns should we use when talking about the character of Jet? Because Jet uses different pronouns at the beginning of the book, and at the end. So how should we talk about this character?

Well, I use they or he. I think they both make sense. The English language has that really great option of saying “they.” It has been complicated how to approach this in the book blurb. I don’t want to give away too much of what’s going to happen.

Yes, you don’t want to spoil the story.

When I first brought the book out in German, I used “she” in the blurb because that’s how Jet identifies at the beginning. I’m okay with that. I personally don’t use the word “deadname.” I don’t feel my old name is dead, and it’s just the way I identified then. But in terms of putting the book out there in the world … the blurb affects how it’s marketed and the way it’s placed in the bookstore. We need to make decisions in the beginning in our blurbs, which will affect the book so much—such as, whether you mention it’s a queer book on the back or not.

Yeah, you want people who are looking for queer books to be able to find it. But you also don’t want it to be pigeonholed or censored.

Exactly.

I love the character of Jet. The growth they make is fascinating. I also love the friendship of Jet and Sasha. Can you talk a little about writing a teenage friendship?

I had that type of friendship myself, and I think I was really trying to portray what that friendship was for me, which was very intimate. The thing I like about storytelling is that you take the truth and then you kind of edit everything out that isn’t necessary and then you kind of end up with— what is that called …

Like a condensed version?

Yes, condensed. You take everything you don’t need and filter it out.

Another part that I loved was the collaging that Jet does, and there’s a specific moment where Jet glues a picture of their own head on a picture of Kurt Cobain. And it reminded me of how, as a teenager, I made tons of collages and I would specifically cut out pictures from newspapers of anyone who looked even a tiny bit queer or androgynous. I felt like I was collecting these scraps of queerness in an era where I didn’t have the abundance of queer content that is more available today. Is that something that you relate to or that you were thinking about?

The collaging—I think that’s an example of how a lot of these scenes in the book are mixtures of things that happened and things that I invented because I needed to show something in this story. I do use things that really happened. But I might change the person who did it, or might change what exactly happened. I was going to start by saying the collaging was fictional. But then I realized when you told me about the type of collaging that you did that I actually did something that’s really funny when I was quite young, and I don’t know why. But I would gather the advertising flyers that came in the mail, and I would cut out the pictures of the male underwear. And I would just paste them into a book. And I just had pages of these models, but just their underwear.

That sounds like a young person who is searching for something that they don’t have language for.

Exactly. And I didn’t know what I was doing or why, and I’m not even sure that I ever reflected on that. I just did it for a while. And then at some point, I threw them out and I never thought about it. But I guess it appealed to me somehow and that drove me to cut it out and paste it.

Saving and collecting whatever you can find; whatever is speaking to you.

Yeah. And it’s visual. I wasn’t comfortable drawing them, even though drawing was a really important thing in my life growing up as a kid. I was super, super shy. My favourite thing to do was to bring a sketchbook everywhere, and then I would just sit behind my sketchbook, which, on the one hand, allowed me to sit in the corner. On the other hand, if I wanted to talk to people it gave me something to talk about. It gave me an identity. People left me alone because of it. They just kind of respected me and ignored me or liked me because I could draw. But it kept me out of problems and it was very, very comfortable. And I never drew as much afterward as I did during that time. I didn’t draw men, but I did cut out those weird underwear.

It sounds like the sketchbook was both a shield and a prop in social situations.

Yeah.

And I love the description of Kisses for Jet as a collage. A collage of memories and fiction layered together.

Yeah, yeah, definitely.

One major theme of my teenage years was this hunger for representation and information. For anything I could find to help me figure out who I was. I felt that same sort of hunger in the character of Jet. That searching. There’s a scene where Jet steals a pair of boys’ underwear from the laundry room at the boarding school. And later, finds a magazine of sexy pinup images of men. It’s almost like trying to collect little pieces of masculinity that feel accessible, but also keeping them very hidden. Jet also tries to chest-bind using an ACE bandage, with mixed success. I thought all of those scenes were really powerful.

Collecting all these scraps, these collages and trying to make the pieces fit together into one picture, but not having that picture to compare it to. The feeling that really pushed me to make a book was this large feeling that my whole identity felt like a question. When I came out to myself, when I realized I was trans, I also realized how vague everything was. The reason I think it took so long to understand I was trans is because I had only seen one kind of trans narrative, a narrative that was always very clear.

That narrative of “I always knew.”

Yeah. “I always knew I was in the wrong body, because it was supposed to be the opposite.” Very black and white. And I realized actually everything I had felt my whole life had been very, very vague and all over the map. I wanted to give some of those feelings to Jet. Jet is attracted to boys, so in that sense, Jet is doing the normal thing. It’s expected that a person assigned female will have boyfriends. But when Jet acts on that attraction, what happens is they feel kind of closed in and not right. They run into walls everywhere and just kind of bumping into things and not really understanding what’s going on. That’s what I really wanted to show. Just a lot of vagueness.

I think that’s really important, to show more gray areas, more complex, nuanced narratives. More of an “I didn’t always know” storyline. Personally, I spent a long time wrestling with uncertainty about my identity.

I want the generation that’s coming up now to realize you don’t have to know what you are. You don’t have to choose man or woman. You can live happily without knowing.

Yes. We need nuance and thoughtfulness and space for variety in the world.

I think that’s where art comes in, and that’s why art is so necessary. Art and stories are one place where things don’t need to have endings, where meaning can be open, where you don’t have to choose sides. That’s specifically the reason I wanted to be an artist. My dad’s work was about politics and I realized, very quickly, I can’t do that. I never see one side of the story. I never agree with one side of the story. I’m always constantly seeing both sides or all sides. I’m constantly contemplating things without coming to a final conclusion. And that’s why early on I wanted to be an artist because I felt it was the place where I could speak the way I felt and where I could just keep on reinvestigating everything. That’s what art means to me.

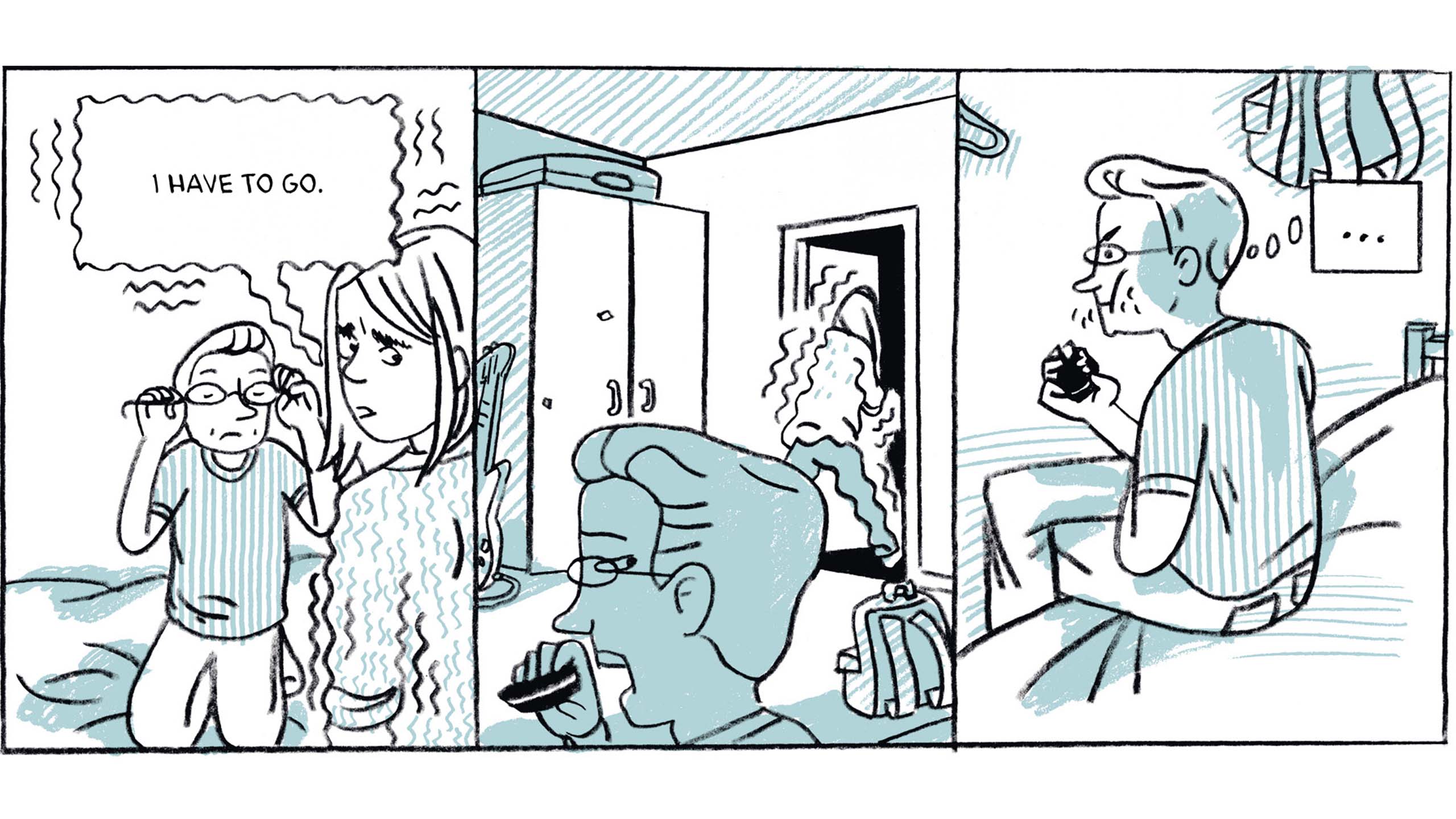

I want to talk about the art in the book! The pages have a beautiful scratchy, expressive teenager-ness. I really love the way you drew this book, but I specifically wanted to talk about a couple of scenes right after Jet makes out with a boy at school. You made some really interesting art choices to express Jet’s mental state. You drop the panel borders off several pages so all the panels are kind of cramped in together and then, in a moment of extreme discomfort, Jet freezes into the shape of a rectangular box. I love this whole sequence. Do you want to talk about some of the comics choices you made here?

Yeah. I dropped the bordering and pushed the panels into each other to try to make it go faster, and feel more tense.

Credit: Joris Bas Backer

It’s a bit claustrophobic.

And then they become this box. It was kind of an emotional or intuitive thing I drew. I didn’t really think about it. That was how I thought to depict that feeling. Like becoming stiff and becoming more of an object. Untouchable. As if your whole body is saying, “I can’t be this body now. I’m going in here and the rest of the world stays outside.”

That also speaks to how I like to work. I don’t plan everything out, I kind of vaguely write the story, but I’m most creative if I just create the story while I go. I outline it very loosely. But then when I’m on the page, when I’m writing it, that’s when I get the ideas because that’s when I’m in the character. And I’m like, okay, now they could do this, or now they could say that, and I can always go back and change things if it doesn’t work. But sometimes it just comes one panel after the other.

Wow. So these art choices are being made at the pencilling stage?

I do some really basic thumbnails. They help me set up some panels so I kind of know what’s happening. But they’re super basic, so I can still go and change things. And then the pencilling is where I just drive myself crazy. I spent forever on pencilling, the hard thinking and it’s not fun. It’s just hard. And then the black lines come in, and that’s the really fun part.

I think every cartoonist has a favourite and least-favourite stage of the comics-making process.

I really like those creative moments that I don’t see coming. I don’t consider myself a creative person, but I like how I’ve learned over the years to create that moment where creativity can come in. When you’ve had two coffees and your table is clean. I’m drawing and I can be in the character, then all of a sudden I can be like, “Oh, this is what they would say. Oh, this,” and things happen I could never have thought of if I were just writing at a computer or something.

I love those moments where it seems like the character is coming to life and is starting to speak in their own voice. That’s always very exciting. Is that part of what drew you to comics rather than another form of storytelling?

When I found out about comics, it was really like coming home. I love the medium. I love the fact you can write the story and people take it home and then they can read it at home and it’s theirs. And I like experiencing other stories in my private space. And the other side is that you get to be complex. You can spend two hundred pages explaining a certain feeling.

Oh, I love that about comics too. I’ve always wanted to make art that is mass-produced so that it can be accessible and read by many.

Do you work in a library?

I worked in libraries for 10 years as a day job, but I have quit and gone freelance cartoonist full-time. But I love libraries.

The most celebratory moment after publishing my book was going online to the Berlin libraries and seeing how many people had checked it out. You can go there and see how many copies of my book are in the library, and you can see when they’re checked out. I love that.

Yes, I know exactly what you mean. I was so happy when I went into the library system of my childhood and saw my book there, with the sticker of the county library from where I grew up.

It’s so good. I think as an author you are supposed to be thinking about the reviews. But I haven’t done that at all. I’ve just been nerding out on the library website.

All the cool people are nerding out on the library website.

They have really great comic sections in the Berlin libraries. The one near my house has a huge space for comics. It’s awesome.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra