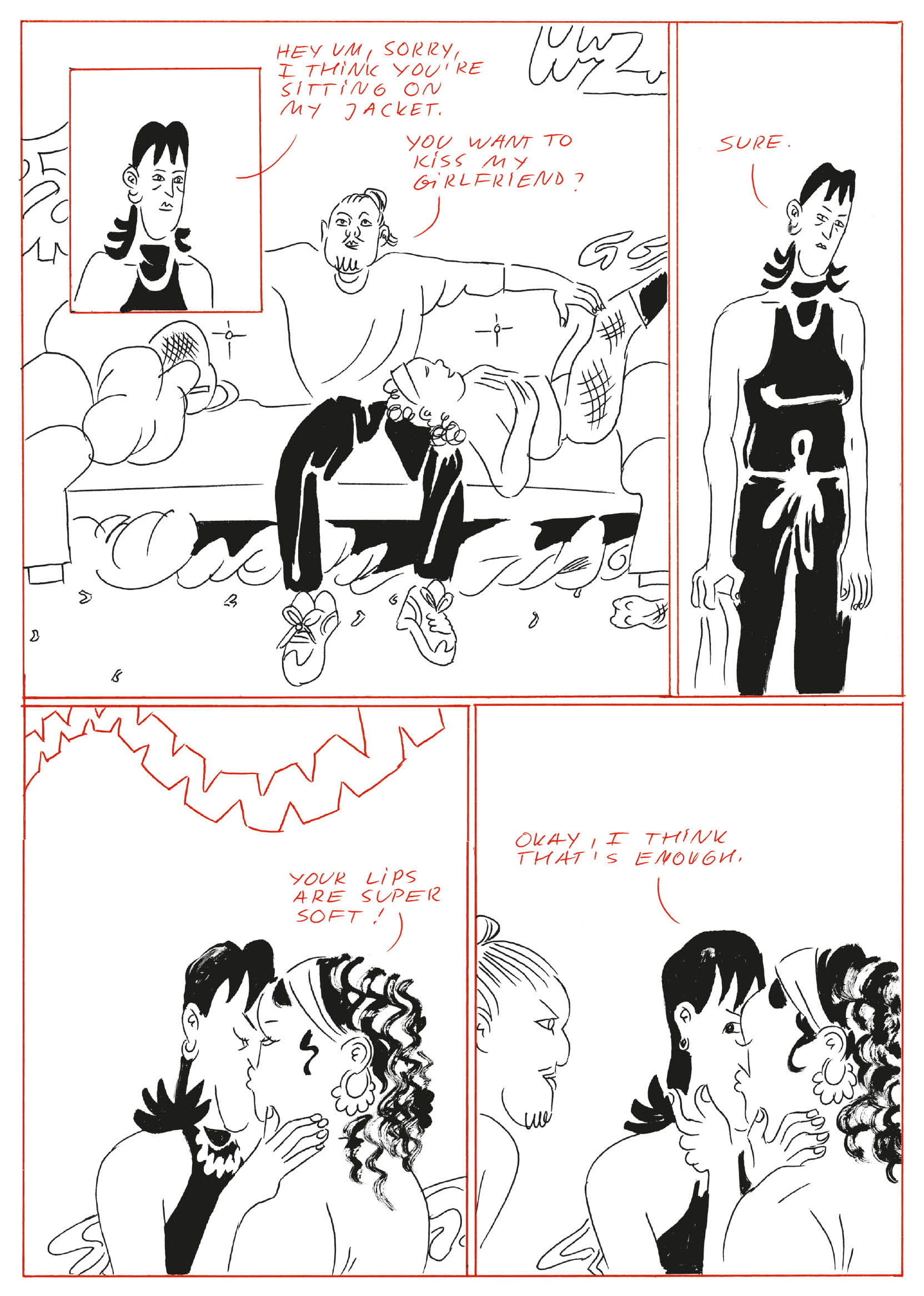

Nino Bulling’s new graphic novel Firebugs opens with a packed scene in a Paris club. We’re treated to an immersive montage of after-hours party images in black and white, framed in red: people dance, flirt, stare, snort and luxuriate, clad in bold patterns, mesh or bare-skinned, adorned with piercings, shades and the collective aura of a crowd high on K and techno. We zoom in on one person, tall with a classic queer mullet, who is having a moment of malaise: Ingken, our protagonist, is not feeling the collective high. They are briefly taken care of by a friendly stranger, and then, after making out with a man’s girlfriend (at his suggestion, with her consent), they get weirded out by his staring, and eject into the daylight.

At the club. Credit: Nino Bulling/Drawn and Quarterly

This opening scene sets up some of the themes of Firebugs: sudden unease within what appears to be a friendly, supportive environment and discomfort with other people’s perceptions of one’s gender and sexuality. Anyone who’s spent time in after-hours clubs will recognize the unexpected shift in mood that can take over in the middle of the dance floor, whether you’re high or sober. Surrounded by friendly strangers, overcome by an acute feeling of aloneness. When we hit this wall, we might either take stock of it and figure out how to soothe ourselves enough to re-enter the party, or we might spiral, until the dissonance becomes too big to handle, and we’re forced to leave. Either way, decisions need to be made. In Firebugs, Ingken, both in the club and out of it, is beset by increasing gender dysphoria, accompanied by the overwhelming inability to make decisions about how to address it. Back home in Berlin, they tell their partner Lily that they don’t really feel like a woman. This isn’t a scene of rejection or strife: Lily is trans herself, has been on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for years and is unsurprised by Ingken’s declaration. “I’ve never seen you as a woman,” she assures them, and Ingken replies that that’s why they feel so good with her. The drama of Firebugs is not that of a trans person being rejected by their partner; the plot’s conflict is more creeping, more subtle. Bulling is a talented comic artist, who already has an established career in comics (they’ve published four graphic novels to date) and visual art in their native Germany. Firebugs will hopefully mark the beginning of an extensive career for the Berlin-based author in English, as well as in German.

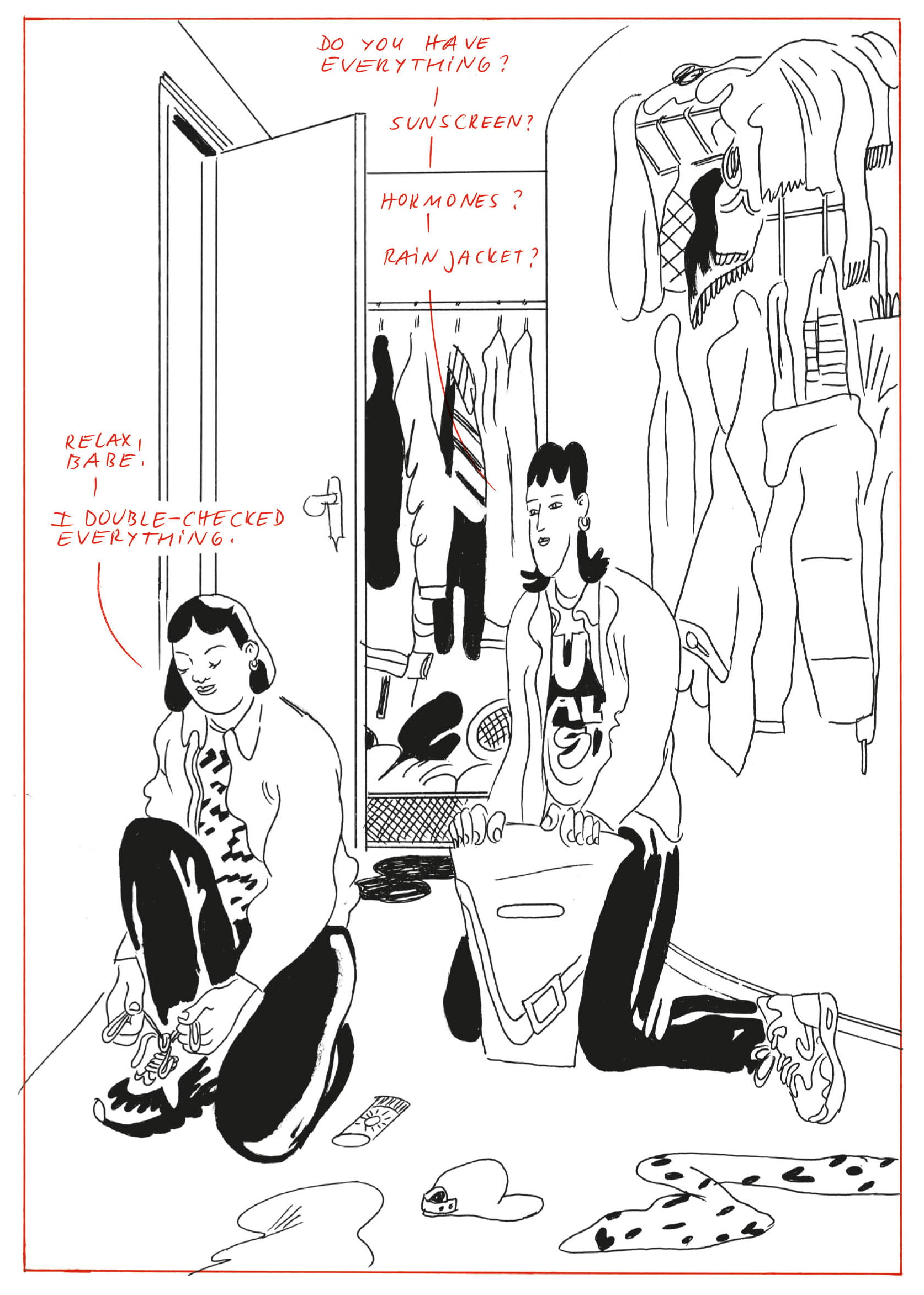

Getting ready for a trip. Credit: Nino Bulling/Drawn & Quarterly

Over the course of the book, Ingken becomes increasingly stuck. They are riddled with doubt: they worry out loud that the way they want to look as a transmasc is “cliché.” Lily is encouraging: “You’d be really hot as the quintessential muscular, androgynous babe.” “I don’t know,” says Ingken, with a perplexed expression. “Would I?” Lily is supportive, but her impatience grows. “Thinking will only get you so far,” she asserts, reminding them that when she started HRT, “I didn’t have a big master plan. I just tried.” Lily is someone who makes decisions and takes action. Ingken is someone who stews and worries. This difference begins to cause a rift in an otherwise loving, sexy relationship.

Fuelling much of Ingken’s anxiety is the climate crisis, which is omnipresent in Firebugs, as is the natural world. Bulling uses black and white in most frames, but draws certain key elements in red: sound effects; the trajectory of insects; and flames, both the tiny flames of matches and the destructive flames of forest fires. Using very little text, they are able to create a deeply felt atmosphere of pervading dread. In an Instagram post, Bulling reveals that their major inspiration for Firebugs was Seiichi Hayashi’s Red Colored Elegy, one of my all-time favourites in the genre. They sought to transpose Hayashi’s narrative style, which is dialogue-only and without narrative exposition, on to a t4t relationship. Red Colored Elegy, which was first serialized in Japanese in the manga magazine Garo in the early 1970s, and published in English by Drawn & Quarterly (Bulling’s English-language publisher) in 2008, accompanies a heterosexual Japanese couple, both artists, drifting through life together with increasing melancholy and disconnect, in a postwar Japanese society that is financially and artistically inhospitable to them. Hayashi was himself deeply inspired by the fragmented yet intimate style of French New Wave film. This impressionistic, fitful visual language is perfectly suited to Bulling’s project: scenes of intense affection and brief joyous gatherings occur amidst the growing certainty that something is off, on both a micro and a macro level.

In the post, Bulling also credits Andrea Long Chu’s clever, divisive Females with influencing how they portray gender dissonance and dysphoria in Firebugs, especially Ingken’s inability to present themself publicly the way they feel inwardly. Bulling points to Long Chu’s assertion that “Gender exists, if it exists at all, only in the structural generosity of strangers.” Here is where Ingken flails. They go as far as choosing a new name for themself, which they share with Lily, but they won’t let her call them by it, let alone tell anyone else.

Having gone through the awkward process of renaming myself some years ago, I recognize the cringing embarrassment and hesitation that can accompany this decision—sharing the new name over and over, insisting that other people abide by it, a decidedly fake-it-till-you-make-it undertaking. Choosing a new name and coming out as trans requires drawing a certain kind of attention to oneself, which not everyone is comfortable with—and which, of course, can be legitimately dangerous, depending on the environment in which a person lives. For those of us, like me and the characters in Firebugs, who live in relatively queer- and trans-friendly bubbles in cities like Berlin or Montreal, it is possible to move through the discomfort in order to tell people how to perceive us. If others don’t know our new names, how will they address us by them? If they don’t know what our genders are, how will they validate those genders in their interactions with us? Here lies Lily’s growing frustration with Ingken: not that Ingken is trans, but that they are defeatist about it, turning increasingly inward, pushing Lily and others away because they can’t bring themself to risk change, while hating how it feels not to.

Change can mean renewal, but it can also mean loss. Ingken and Lily’s relationship is polyamorous: Lily has recently started seeing a new lover, which adds to the shifting moods of the couple. A friend of Ingken’s tells them about a piece of performance art that invokes the phoenix as an allegory for the climate crisis. Ingken reacts negatively to the suggestion that they should embody the phoenix—go through some major changes and emerge from the flames, renewed. Their reaction is partially due to the fact that the performance was put on by Lily’s other lover, but their rejection of the concept runs deeper than polyamorous jealousy. They are perturbed by the summer’s forest fires, which have become an annual catastrophe: “There is no magical resurrection. Things burn, and when they’re burnt down, you’re left with piles of ashes and debris and burnt-out cars. And fire devours everything, you can’t pick and choose. But what if I want to keep certain things?” It occurs to me that polyamory, which Lily seems more committed to than Ingken does, also requires a belief in one’s ability to change and transform, without leaving one’s entire identity or relationships behind. Lily believes that changing doesn’t mean losing everything, while Ingken fears the destructive force of the uncontrolled burn. Ironically, Ingken risks losing their partnership and perhaps also their mental health by refusing to change when they need to.

Stories about strife in relationships between trans and queer characters can be heavy to read—interpersonal dysfunction and romantic betrayal hit extra hard in communities that are already politically and culturally under threat. At the same time, stories like these can help to complicate misconceptions about trans people being some kind of monolithic horde. They also refute the idea that simply embracing one’s sexual and/or gender identity automatically makes things easier. Bulling writes into a growing body of trans literature that highlights complexity, contradiction and ugly feelings, alongside gender euphoria and trans solidarity. Casey Plett’s A Dream of a Woman, her 2021 story collection, portrays a wide array of relationships between trans women. One of its stories, “Hazel and Christopher,” features a newly realized t4t couple. One character, like Lily, has been out for a long time and the other is just coming into her transness during their relationship. Instead of this self-clarity leading to increased understanding, love and support in the relationship, the second character’s coming out elicits a horrified reaction from her girlfriend. Hazel abhors the idea of guiding Christopher through her transition; she fears reliving her own early painful days of the same.

In Firebugs, Lily is open and supportive about Ingken’s gender feelings, but becomes increasingly beleaguered and alienated by Ingken’s failure to take any risks in having their transness recognized by others. Her impatience is painful to Ingken, but we understand that it comes from a place of having already undertaken the multiple risks of coming out as a trans woman, and just wanting Ingken to take the plunge already, to stop hesitating and hand-wringing and get on with it. Conveniently, Lily can escape their relationship tensions by spending more and more time with her other lover, which serves to further distance her from Ingken. In these two fictional relationships, love isn’t lacking; however, the simple fact of both partners being trans does not automatically lead to mutual support, patience or long-term compatibility.

Throughout Firebugs, Bulling draws the world with expressive detail, and maintains the fluctuating interplay between personal dramas and the looming climate emergency—whether it’s Ingken and Lily struggling through emotional tension while hanging out in a series of massive pipeline segments; Ingken scrolling their phone while lying in bed with Lily, taking in worrisome headlines about wildfires, or Ingken’s father grumbling about his garden turning yellow every summer now, while Ingken’s mother keeps misgendering Lily during an awkward family visit. As with all good graphic novels, we can’t separate the art from the text—they are expertly entwined, making Ingken and Lily’s world feel immediate and lived-in, from their artfully messy Berlin flat, to the clubs they frequent, to their trips into the overheating German countryside. The deft touches of red ink characterize Ingken’s prickling fears—fires both literal and figurative, the unstoppable nature of change. What can we keep when we are required to transform? Bulling allows Ingken to sit uneasily with this question, and we are invited to sit with them in their stuckness, until the time comes for them to choose something new.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra