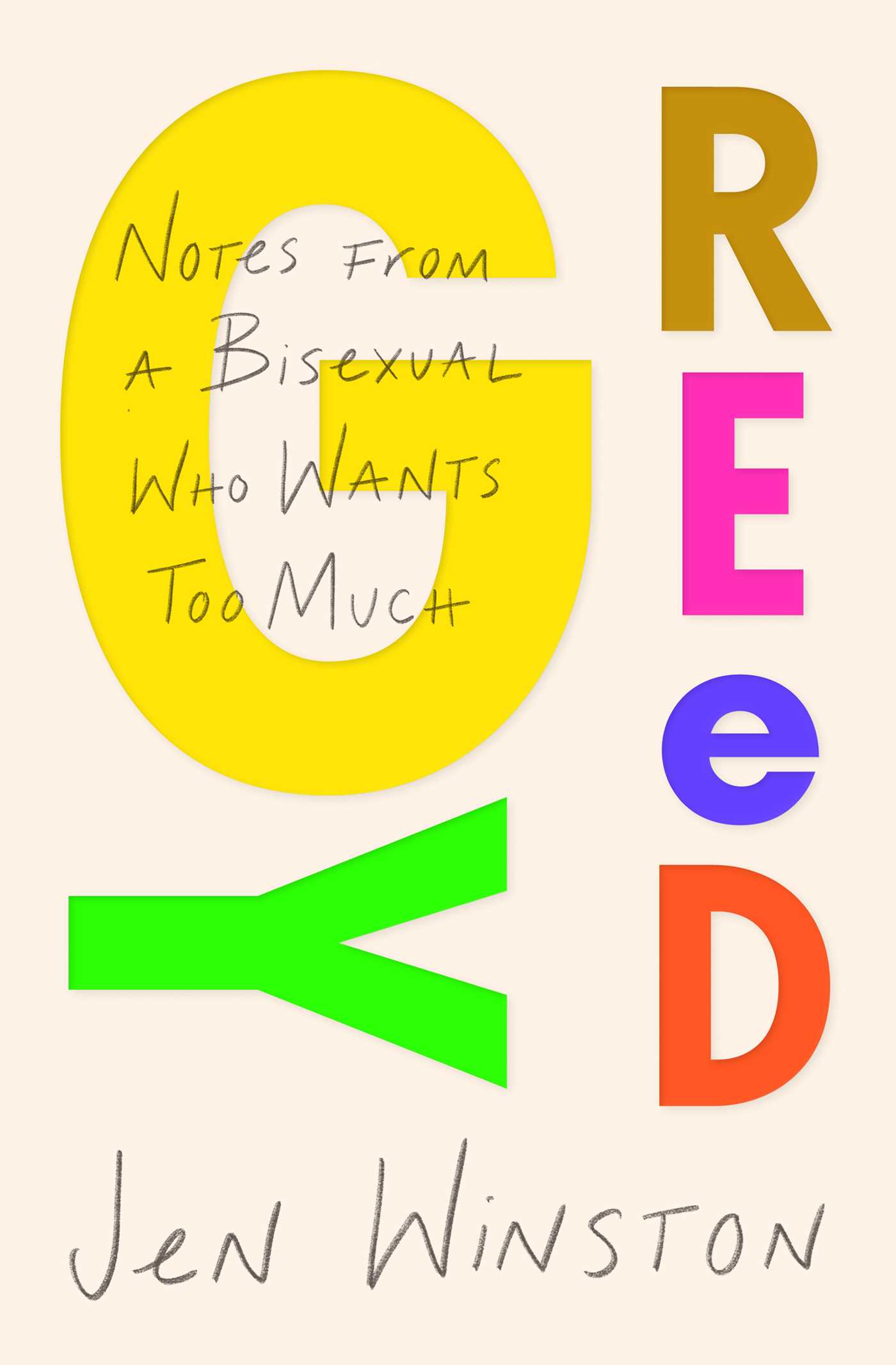

Greedy: Notes from a Bisexual Who Wants Too Much is Jen Winston’s exploration of their lifelong journey learning to confidently own their bisexual identity. In a series of sharp, endlessly engaging essays, Winston examines why it was so difficult to loudly and proudly proclaim themselves as bisexual.

Through relationships, dates, hook ups and more, Greedy chronicles Winston’s desperate attempts to become “queer enough” and prove to both themselves and others that they are a valid member of the LGBTQ2S+ community. In Greedy, Winston becomes a detective looking into their own life, excavating texts, emails, conversations and research in an attempt to understand the systems in place that compelled them to exclusively date cisgender men for so long.

Along the way, they come to realize how much of their confusion was rooted in patriarchy and the rampant biphobia that persists today. This discovery helps empower their fight to overcome all that has been holding them back.

From figuring out queer sex to deciphering the difference between friendship and lust, Winston paints a painstakingly honest portrait of what it’s really like to navigate a world built for straight, cisgender people as someone who identifies as neither.

Greedy is not just an exploration of bisexuality; it is an ode to it, and an ode to all who live outside the gender and sexual binary.

In a phone conversation with Xtra, the Brooklyn-based Winston spoke about the impact their story has had on readers, the most common misconceptions about bisexuality, writing sex scenes and why bisexuality is a political identity.

Now that the book is out, what has been the response?

I’ve been amazed at the number of messages I’ve gotten that have all been people just so grateful that a book like this exists. I definitely don’t want my book to be held up by any means as the bisexual story, as if there only is one, so I keep telling people that it just shows how hungry the bisexual community is for content that speaks to us directly.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about bisexuality that Greedy addresses?

Credit: Courtesy of Simon and Schuster

The biggest one is probably this idea that everyone is bisexual. I think people think it’s sort of a compliment or that they’re saying that they aren’t afraid of you. But when you say that everyone is bisexual, what you’re really saying is that no one is bisexual or that it’s not an important enough experience to talk about.

That’s part of the reason that so many bi people stay in the closet. After I came out, I started reading a lot about bi theory and it talks about stuff like this and also how a lot of bi stereotypes—even being greedy—play into these other systems like patriarchy. “Greedy” implies that promiscuity is a bad thing, which is a different issue than being bisexual.

So often bisexuality is used as the scapegoat for a lot of these systems; I found that [perspective] to be really empowering. I didn’t ever realize that bisexuality was something I aligned with politically as well as in terms of my personhood. So that made me be like, “Oh, I could definitely write a book that combines everything I want to say through this lens.”

What made it the right time to write this book? What sort of understanding had you gained about yourself that you felt you could now share with readers?

It was really understanding bisexuality as a political identity. With that I credit the work of Shiri Eisner, who wrote a book called Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution, which is quoted throughout the book. One of my favourite quotes of Shiri’s that is not in the book is the idea that bisexual confusion can be thought of as a destabilizing act of social change, which I think is just so empowering.

Is that what you meant in the prologue when you wrote that bisexuality is “a lens through which to reimagine our world”?

Yeah, for me what it stands for is looking past binary options that are presented to us and asking questions like: Is this right for me? Or is maybe something in the middle right for me? Or is maybe something else entirely right for me? Just really questioning the social norms.

I love rethinking bisexual confusion in that way. The book is a bit about finding power in that confusion and that mindset. If “Confused” were a catchier title, that might have been what I went for.

One essay explores your first time having sex with a woman, which didn’t go that well. Was it difficult to be so honest about your sex life?

It was harder to write good sex without being cheesy. There’s not that much good sex in the book. The lack of sexual confidence I had in a queer sex scenario was a huge part of my inability to come out because it just meant I felt so much more comfortable having sex with men—cis men specifically.

That was the entirety of my sexual experience, and I think a lot of queer people, regardless of how you identify, feel this way. When you start to explore your queerness, you feel awkward and fumbly and you feel a little bit too old to be doing that if you come out later in life.

You also get really raw and honest about childhood trauma and sexual assault. Why was it important for you to include those stories?

I was really blown away by the statistics about issues that impact bi people specifically, like nearly half of bisexual women are sexual assault survivors compared to 17 percent of straight women and 13 percent of lesbians. That’s an exorbitantly higher percentage.

When I looked at those, I was like, “Is bisexuality really a big enough deal to have this effect? How could it possibly be?” That ultimately was my own internalized biphobia not allowing me to see bisexuality as important enough to cause those statistics or to cause those issues, and so I wanted to include some of the chapters about sexual assault because it’s true to my bisexual experience and apparently, it’s true to half of bisexual women and femme people’s bisexual experience.

How do you understand your bisexuality and identity today as compared to the person you were in this book or even the person who began writing it?

Writing the book really helped me get to thinking about gender and realizing that this idea of womanhood doesn’t really serve me anymore.

I’ve actually noticed from TikTok that this is a common journey for a lot of bisexual people, to figure out our sexuality and then begin to unpack our gender. I think it’s because bisexuality gives us the tools to do it, because in order to be comfortable in your bisexuality you have to be comfortable existing outside of binaries.

Now, I’m getting more comfortable saying this, but I identify as non-binary femme and I use she/her and they/them pronouns, and I feel good about that.

How do you think about the concept of bisexuality in relation to non-binary identities and they/them pronouns?

One of the reasons I wanted to write this book actually is because there’s an assumption that bisexuality, because it has the term “bi” in it, implies that there are only two genders. Bisexual activism has always been very gender inclusive—probably more so than a lot of other queer activism.

The way that I define bisexuality and the way that a lot of other bisexual activists define bisexuality is the same as how a lot of people define pansexuality.

For me, it was really important to debunk that myth that bi means two and that bisexual people are reinforcing the gender binary. There are so many non-binary bisexual people, including myself and my partner.

What is the biggest thing you hope readers gain from reading Greedy?

For a long time, I didn’t realize bisexuality was something I could be proud of, so I hope readers walk away either feeling proud of their bisexuality or proud of someone else’s bisexuality or just happy for bisexual people.

The biggest takeaway for me is that bisexuality is a superpower and the things about it that we think are detrimental—like being confused or being greedy—are actually superpowers in the way that they challenge the status quo.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra