In the United Kingdom and beyond, right-wing rhetoric paints trans people as unhinged villains who don’t have a handle on their desires. Trans men regularly have difficulty getting testosterone because it’s a controlled substance. Trans women, routinely denied medical care, are forced to launch GoFundMe campaigns. To contend with the fiery landscape around us, writers rip up the roots of our current moment by using horror tropes to look into the eyes of the beast. The growing genre of trans horror fiction, from Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt to Torrey Peters’s Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, is distinctly well suited to grappling with the nightmare of our present moment.

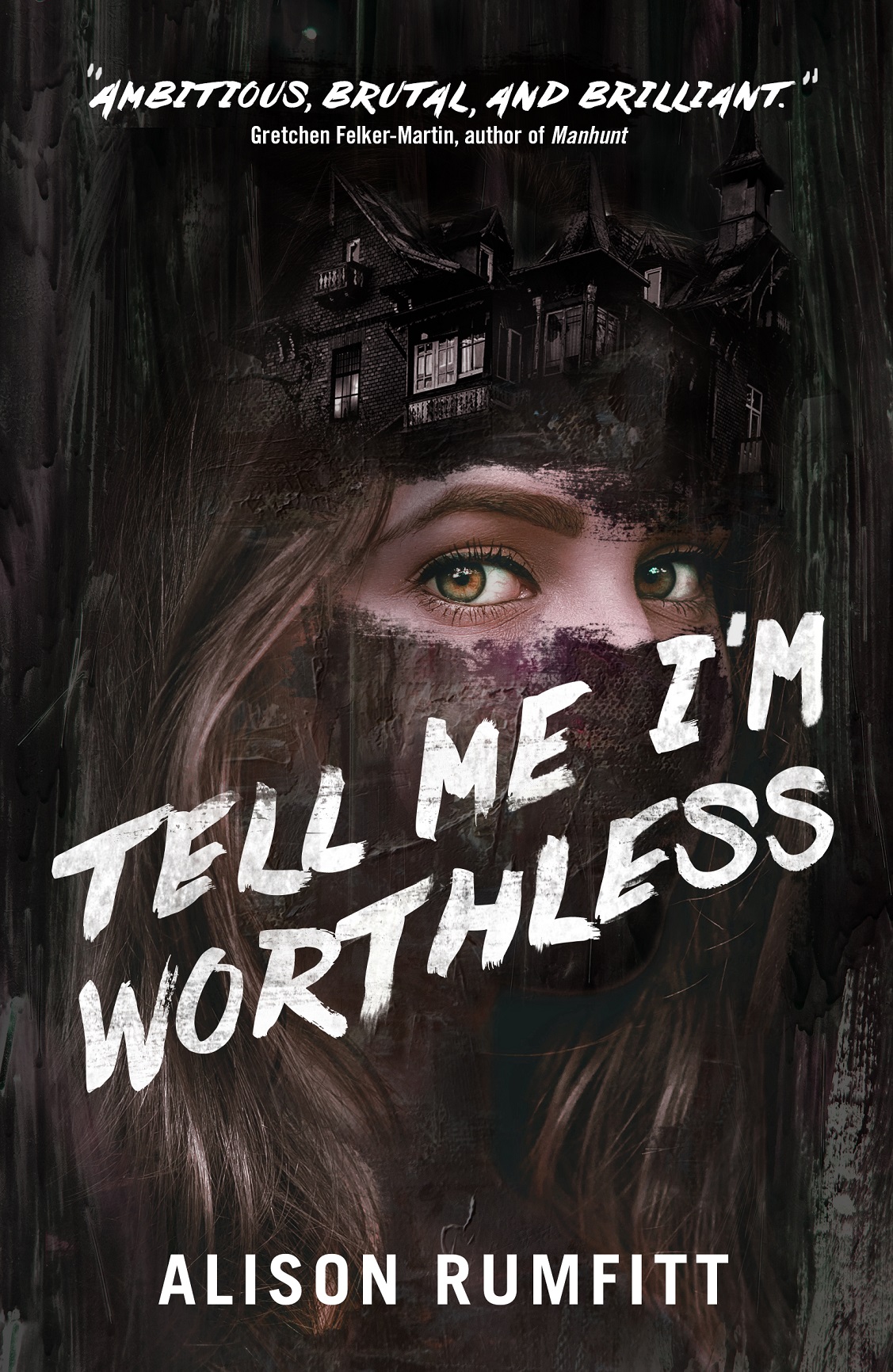

Alison Rumfitt’s debut novel, Tell Me I’m Worthless, which came out last month, plunges into the genre with a twisted take on the haunted house story. The English author builds on the gothic tradition of Henry James and Shirley Jackson with her own gritty take on trauma, transphobia and far-right propaganda.

One night, a few years before the novel starts, three women enter an abandoned house and only two come out. Alice is a young college-age trans woman, Ila is a lesbian cis woman and Hannah is their token cis straight friend. At first, Rumfitt gives us few clues how Hannah fits into their triad, other than that she is not romantically interested in either of the other women. “The House” had been sitting empty for years, becoming the subject of rumours and legends as their town’s public infrastructure crumbled. The three young friends enter it in order to protest capitalism and a lack of affordable housing. At first, readers are unsure what happened that fateful night in the House other than the fact that Hannah does not escape with them. We also learn that both Alice and Ila believe the other raped them that night.

“No one cares. The only people that care are people you don’t want to be around anyway. But another part of me, a vicious little creature that claws at my head, calls me a fucking brick sissy, whispers everyone can see your stubble everyone is creeped out by you in the toilets.”

In the aftermath, the novel follows three narratives: Alice’s jittery first-person account, Ila’s lonely third-person and a strange hallucinatory narrative that may or may not be the House’s interior monologue. These years later, both Alice and Ila are traumatized, struggling to contain their own self-loathing.

Since college, Alice has moved from one apartment to another in her dismal English town, surviving by filming sissy hypno porn and working the occasional odd job. She rarely leaves her apartment or makes new friends, afraid of the claustrophobic shadows on the wall and the haunted poster of a racist musician she can’t seem to let herself get rid of. Alice can’t move through her trauma, refusing to contemplate exactly what happened at the house, while at the same time being unable to let it go. Her mind is a hamster wheel, cycling through paranoia, passing and betrayal: “No one cares. The only people that care are people you don’t want to be around anyway. But another part of me, a vicious little creature that claws at my head, calls me a fucking brick sissy whispers everyone can see your stubble everyone is creeped out by you in the toilets.”

Meanwhile, Ila is ensnared in her own form of denial. After cutting Alice out of her life after their night in the House, Ila has become a TERF. She speaks at conferences and writes articles about protecting the sanctity of women’s bathrooms. Her family provides her with enough economic security that she’s able to eke out a living while getting off to sissy porn on the internet. Occasionally she imagines she has “a penis pushing through her pussy lips.” Here, Rumfitt hints at the way TERFs’ obsession with transness often betrays their own sexual predilections.

The two ache for one another even as their memories of the night in the House paint the other as a rapist. The two no longer share a common reality—it’s been broken both by the House’s supernatural power and by the fractured political climate of the country they live in. After a fellow TERF makes an unwanted pass at her, Ila tries to contact Alice. “Something is happening to this country,” Ila says. Both women feel the country rotting. Things begin to spiral as the House manipulates Ila into luring Alice back inside with the promise of an end to their trauma.

The House, we learn, is Albion, “the Giant, the mythical founder of Britain.” A physical manifestation of fascism, it reaches from both the past and the future to claim its inheritance. The House as fascism is one of the book’s most striking metaphors; how it’s done reminds the reader of Rumfitt’s career as a poet: “Things from the future, pushing back into the now because they are so utterly traumatic that they can’t stay within the limits of the time, they have to be happening now, around you.”

The scars that Alice and Ila hold from the House are physical as well as emotional. Alice finds a cunt on her forehead and dubs herself the “Harry Potter of transphobic hate crime victims,” while Ila finds racial epithets on her abdomen. Each carries their own permutation of privilege and violence: Ila spews transphobia, while Alice’s narration betrays her own undercurrent of anti-migrant xenophobia. At one point in the novel, Rumfitt discusses an “intersectionality calculator” to highlight the different ways people endeavour to find solidarity under fascism. According to the calculator, Hannah, the straight cis friend, is the most privileged. Ila, on the other hand, as the daughter of a Jewish mother and Pakistani father, is less protected from the outside world. These power dynamics affect who the reader might be identifying with or siding with. “Do you take the side of the woman who is most like you? Or the most intersectional one? But one is rich, and white, and trans, and the other is rich, and Asian, and a lesbian, and cis (?), and fuck, who wins here?” Winning may be beside the point.

Tell Me I’m Worthless makes the case that the fascistic tendencies that infiltrate our everyday lives can limit our imagination, forcing us to believe life and politics are a zero-sum game. By exposing the psyches of her protagonists, Rumfitt is able to lay bare our need to bring ourselves and others in line with some imagined normality. In Rumfitt’s world, fascism has seeped into the roots of a country, embodied here, in “the House.” This fascism forces minorities to move in smaller and smaller spaces, running up against manufactured scarcity and bloodlust. TERFs and white nationalists become one malignant force bent on gaining control of the country they believe to be rightly theirs. The House declares that only cis straight white people should inhabit England, pitting everyone else against each other. When resources are scarce, those living under fascism can be motivated to either work together or find themselves fighting over scraps.

“As Alice and Ila struggle to see the ways they hurt each other, we’re invited again and again to re-examine their perspectives. The way one identifies will inevitably influence who a reader empathizes with more—at first.”

Rumfitt has written a terrifying book, pushing her characters into the far corners of defensive posturing. Both Alice and Ila struggle to see the ways they hurt each other, and we’re invited again and again to re-examine their perspectives. It’s true, the way one identifies will inevitably influence who a reader empathizes with more—at first. But Rumfitt does an excellent job at challenging our assumptions of sympathy and deservingness. The House creates an environment where “[n]o live organism can continue to exist compassionately under conditions of absolute fascism, even the pigs in Chile under Pinochet’s rule were observed to take part in political killings.”

Near the end of the book, the girls finally re-enter the House and as we learn the fate of the third missing girl, hallucinations flood the hallways. Apocalyptic poetry, satanic mills, attack helicopters and bodies bent into swastikas materialize and dissipate. The girls’ final confrontation with the House is not an easy one. The House taunts them by revealing the extent to which it tortured them all those years ago. As Alice and Ila reckon with their memories, they try to find compassion for one another and move toward solidarity.

While the ending is swift, Rumfitt does a great job at landing the thematic core of the book—the way fascism oozes through the hallways of history. Through her construction of TERF culture to her deployment of British folklore and history, Rumfitt weaves a complicated tapestry of how fascism finds footholds. Alice and Ila’s ultimate fate will leave readers pondering the stake we share in the world to come.

Ultimately Tell Me I’m Worthless is a wicked, compelling read on the limits of identification, the wounds of fascism and the way emotional scars hold us back from seeing the world around us clearly.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra