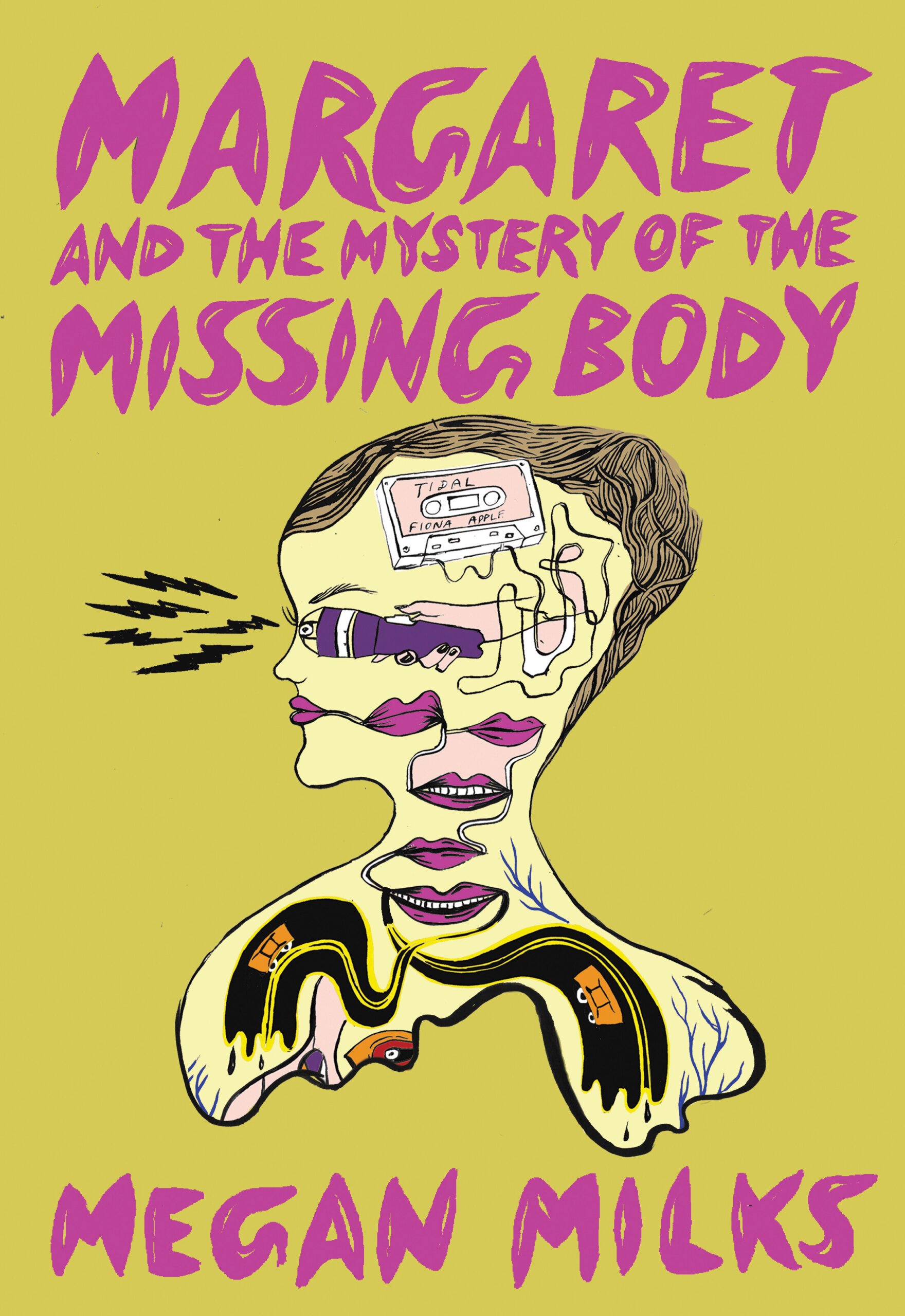

Megan Milks’ debut novel, Margaret and the Mystery of the Missing Body, which came out in late 2021, is one of my favourite indie gems of the past year. Milks mixes the joyful nostalgia of 1990s YA fiction and paranormal fantasy with a sharp, incisive depiction of adolescent queerness, producing a novel that already feels like a queer cult classic.

The titular Margaret is Margaret Worms, former head detective of the Girls Can Solve Anything troupe, a specialist in solving mysteries with a touch of the supernatural (one involves a head missing its body; another features a butterfly-woman). She’s a world-class teenage detective who is growing close to her charismatic fellow crime-solver, Gretchen.

When the group falls apart, Margaret struggles with an eating disorder and ends up at a residential treatment centre. She tries to figure out why she can solve every puzzle except the ones in her own life. She knows that girls can solve anything, but what if she might not be a girl?

What follows is a playful yet serious mashup of The Baby-Sitters Club and 1970s-style body horror that encapsulates the joy and struggle of queer trans adolescence in a sharp, fresh way. It’s also a lot of fun.

Milks has been one of our finest critics on adolescence, friendship and intimacy for a decade, writing about a vast cast of iconic queer writers, from Michelle Tea to Torrey Peters. They are a queer’s queer; I came to their work through an enthusiastic recommendation from author Casey Plett. And 2021 proved to be a breakout year for their writing.

Over a Zoom call, Milks chatted with Xtra about queer YA, the current boom in trans literature and exactly how many bodies are missing in Margaret (there’s more than one).

So, first of all, you’ve had a novel, a short story collection, Slug and Other Stories, and two non-fiction works published in the past year. That’s wild!

Yes! That was partly planned, partly not. Margaret and Slug both came out with Feminist Press within two months of each other, and then my two other projects just happened to be scheduled around the same time. It’s been an abundant year.

One of your non-fiction projects from the past year is We Are the Baby-Sitters Club, an anthology you co-edited that revisits The Baby-Sitters Club series, which is also a clear influence on Margaret. What about the series is a draw for you?

Oh gosh, a number of things. How the series celebrates friendship, and particularly collaborative friendship, was just really exciting for me as a kid. And I think for me and my co-editor Marisa Crawford and for many of the contributors, we’ve taken those lessons about the importance of friendship and the importance of creating things—especially creating things with friends—a lot of us have taken that with us into adulthood and many of us have created things with friends as adults. That’s been very influential for me; I love collaboration and I take friendship really seriously. The babysitting components were the least important or salient aspects of the series for me. I was just really in love with the friendships that the characters had with each other.

There’s a line in Margaret that reads: “Transmasculinity hasn’t solved everything, but it has made me a better friend.” I love the idea of transness as a practice that enables friendship and collaboration.

When I was growing up, if there were conflicts, we didn’t talk about them, we didn’t know how to do that work. One of the reasons so many of us loved the Baby-Sitters Club series is that all the conflicts tended to get resolved: there were problems, they were negotiated, they were dealt with, and that was very comforting and gave us models for approaching conflicts in our own relationships. But there are a lot of conflicts that go unresolved in Margaret, and I guess that’s because the lack of language around queerness and transness, and the lack of language around friendship and intimacy and desire, prevented those conversations from being held.

Margaret is obviously inspired by 1990s YA, and queerness and the representation of queerness has changed so much in the past 30 years. What’s your perspective on YA now?

When I was imagining what kind of book Margaret would be in terms of market and how we might sell it, at times I imagined the book as a YA book. But as a marketing category, YA just didn’t really make sense for the book, even though the content is very YA. These categories are so imperfect and they kind of collapse when you try to make these distinctions, but I was imagining the readership as mostly people in my peer group, so YA didn’t 100 percent make sense, though I’ve been so astonished and excited to see it reaching younger folks as well. Of the queer and trans YA that I have read—and I’ve loved so much of it—it seems like queer and trans YA right now often centres on protagonists who know who they are, they know that they’re queer, they know that they’re trans. That’s wonderful and important, but my book is just not that. It’s really about a pre-trans state narrativized from the perspective of someone who has come into knowledge much later.

How does it feel publishing a novel that explicitly talks a lot about transness now, in this kind of boom time for trans fiction?

This moment is just incredibly exciting, and the abundance and ingeniousness of trans creativity and invention is so exciting to me. The different ways people are writing trans experience, seeing writers work with fantasy in all these different ways, so many different kinds of realism, just so many different approaches. It’s been exciting for me to have my story collection Slug be republished at this time, because many of those stories were originally published many years ago; Slug is the second edition of a book of mine called Kill Marguerite. Most of the stories are the same but some got swapped out, some got swapped in. In some of those old stories I was definitely not trans-identifying at the time I wrote them, but nowadays they totally read like trans stories. That’s been super interesting to recognize, and it’s been great bringing older stories into conversation with newer work that’s more openly trans.

Were there any particular inspirations for Margaret? The way it mashes genres together while retaining a lot of seriousness felt very fresh to me.

There’s a handful of citations at the end of the book, mostly non-fiction books about eating disorders; Nell’s Quilt [a 1987 YA novel by Susan Terris] is in there. Vivek Shraya’s She of the Mountains was a really important text for me; she wrote it before she came out as trans, and it’s more about queer bisexuality and these gender problems that go unnamed, and I think of it as a novel of pre-trans experience, though I don’t know if she’d agree. And then Kai Cheng Thom’s Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars, one of my favourites, which plays with genre a lot and the main character goes on these different episodic adventures. I also read Jeanne Thornton’s Summer Fun recently, which isn’t so much about adolescence but just the description of the character, B; when B’s relationship to themselves gets described, the description really resonated. It’s so bang-on about at least how I experience dysphoria—the feeling of not being real. Other people around you are real, but your own reality is questionable.

I love the focus on eating disorder narratives that takes up the second half of the book, since eating disorders are such an under-discussed topic in adult fiction and YA books that discuss eating disorders often end up unwittingly fuelling them. I remember YA books on eating disorders being very glamorized on the online eating disorder forums I frequented as a teenager.

That was definitely a concern of mine in writing Margaret. I think there’s one reference to calories in the whole book; I really deliberately kept them out. Earlier drafts of the book had a lot of calorie numbers and weights and things like that, and after a while I was like, this isn’t serving anything and it’s potentially triggering to me and to readers.

Why do you think eating disorder narratives resonate so much with trans people?

Trans people get eating disorders at a higher rate than cis people. I think many of us have such fraught, vexed relationships to our bodies, and I think disordered eating practices are one very strongly available way to express that fraught relationship to the body; eating disorders are a body modification regime, sometimes, often. The desire to modify one’s body can easily be expressed in that way through food restriction or binge eating or other forms of disordered eating practices.

That interest in, and revulsion about, body modification also comes up in the first part of the book, the paranormal crime capers that Margaret and her friends deal with in the Girls Can Solve Anything club. That section is a mashup of The Baby-Sitter’s Club, of course, Nancy Drew and also these paranormal series I read as a kid, Goosebumps, Fear Street, the weirdness of the Choose Your Own Adventure series. The paranormal fantasy stuff is a nod to that, and it’s a way to explore weird bodies and fantastic body modification practices that Margaret, as a character, is very averse to. Margaret is just like, no, you can’t do that. That’s a way of introducing trans-related content in a kind of sideways way, because Margaret has no model for transness and would, I think, be horrified or at least bewildered–—she would have been very upset to learn about transgender body modification possibilities!

The book deals with three kinds of mysterious bodies: the body during adolescence, the body within an eating disorder and the trans body.

There are quite a lot of missing bodies in Margaret, it’s not just the one. With the whole detective mystery element, there’s this thing of Margaret as a detective character who, as with many detectives, can see so much but can’t see the things that are right in front of her face. They’re what she can’t solve. I was really interested in using this campy detective trope to explore the mystery of queerness, the mystery of transness.

It always strikes me that something like being queer or trans—which is complicated but in some ways so simple—can absorb so much time, thinking, puzzling. I don’t know another queer or trans person who hasn’t spent years of their life just running through the same questions and getting stuck in the same patterns.

Yes! None of us know how to know any of this, that’s the issue. But we get this feedback from other people who are like, yeah, we knew, we’ve always known. But how?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra