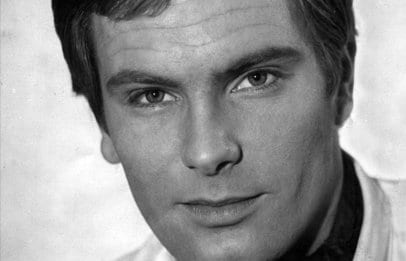

(Previous tributes have only scratched the surface of Ian Robertson’s colourful, often glittering, riotous life./Courtesy of Kevin Dale McKeown)

I live among the creatures of the night

I haven’t got the will to try and fight

Against a new tomorrow, so I guess I’ll just believe it

That tomorrow never comes . . .

—Laura Branigan in “Self Control”

At what point after the dearly beloved are dearly departed do we take the polite mask off memory and let posterity in on the full story?

Do we wait until there’s nobody left to sue, or tell all while there are still enough survivors to know what’s really what in the maze Gore Vidal called “the charnel house of truth”?

Ian Robertson was a minor Canadian arts scene celebrity, beloved dance teacher and mentor, and one of the dearest friends I ever had. Ian died at St Paul’s Hospital almost a decade ago. He died, we said at the time, of riotous living.

AIDS, lung cancer, drug and alcohol abuse, you name it, Ian was at the party.

Ian received many accolades through the years, including an excellent profile in Xtra by Diane Claveau the year before his death. That interview came closest of any to offering a glimpse behind the scenes of Ian’s undeniably colourful and often glittering, careening career. In that interview he shared some of our favourite stories and spoke openly about his alcoholism.

But that hardly scratched the surface of Ian’s life and times. He was fond of aphorisms, and one of his favourites was a line from Canadian author Guy Vanderhaeghe’s The Englishman’s Boy where someone who had behaved badly was referred to as having “backslid and went weedy.”

Ian loved to explain a recent spot of trouble by giving you his most innocent smile and saying “well you know I just backslid and went weedy!”

Every tribute to Ian had to include the story of how he found himself sharing an apartment in Paris in 1961 with recently arrived Rudolph Nureyev and became involved in an international jewel smuggling caper.

“I was going back to Russia for a visit and Rudy asked if I would take some jewels with me that could be sold for cash to help his family. He couldn’t send them money in any legitimate way. So, star-struck kid that I was, I wore thousands of dollars in solid gold chains and aquamarines as though they were costume jewelry and passed them along to our teacher Alexander Pushkin and his wife, who took care of things from there. It all seemed a grand adventure at the time, though it could have gone very, very badly!”

Ian’s career as a dancer ended unexpectedly at the age of 29 when he ruptured all the ligaments in his knee during a rehearsal in Zurich. “I mended well,” he would recall later, “but my knee was never the same.”

The 2005 interview covers all that, but what we don’t hear about is the real antiques heist that led to a brief incarceration in a Swiss prison, which may have had as much to do with the end of Ian’s dance career as the torn ligament.

Nor do we get even a hint of the handsome Russian soldiers on the train from Leningrad to Moscow who invited Ian to share a case of champagne. Weighing a decade of sobriety against champagne mixed with handsome soldiers on a train to Moscow, we all know what happened.

He backslid and went weedy.

And somehow Ian failed to mention to Ms Claveau the lost week spent in a crack tent city in Manhattan en route home from a Festival Ballet alumni reunion in Portugal.

Ian practiced what he called, in a spin on an AA meme, “imperfect sobriety.”

In the mid-1980s Ian and I were sharing a house in Montreal and teachers at Montréal’s École supérieure de danse du Québec, the school of Les Grands Ballet Canadiens, forbade their students taking sparetime classes from Ian Robertson, then teaching in a thirdfloor walkup studio in a downtown warehouse.

It didn’t pay much, but usually kept him in cigarettes and joints. Weediness was our watchword.

Ian enjoyed recalling a similar embargo imposed in the 1950s by his own teachers at the National Ballet in Toronto, banning their students from attending classes by the notoriously difficult, opinionated and gifted Boris Volkoff.

“Of course we would sneak around and take Volkoff’s classes,” Ian would recall years later.

“And I was flattered that Montreal’s dance establishment saw me as a similar threat and that so many of their students and company dancers sought me out and took my classes.”

The attraction, and the threat, both at Volkoff’s home studio and in Ian’s drafty Montreal warehouse, was an almost fanatic fidelity (okay, it was completely fanatic!) to the classical technique of Agrippina Vaganova. It was a fidelity that Ian felt was lacking in much of North American dance and a fidelity to which he devoted his entire life.

In the rarified world of classical ballet, the Vagonova technique as taught to generations of dancers in St Petersburg remains the gold standard for the genre, and there was no doubting Ian’s role as a guardian of that standard, never afraid to speak out on its behalf or to critique those he saw as pretenders, very often to the detriment of his career.

(Ian Robertson, seen here in 2004, continued to teach students at the Scotiabank Dance Centre until a year before his death./Courtesy of Kevin Dale McKeown)

Until his death from lung cancer on Jan 1, 2006, in Vancouver, Ian was a popular teacher and mentor to many young dancers in Toronto, Montreal, Québec City, Moncton, Vancouver, Boston, New York and Mazatlan, Mexico.

It was a tribute to the affection and admiration the dance world had for Ian, who spent his last years on a disability pension, that whenever a major event took place someone would ensure that Ian had airline tickets and pocket money to join the festivities. During the last few years of his life he was in London, England for the 75th birthday of his friend Amanda Barrie (longtime star of Coronation Street), in Portugal for the aforementioned anniversary get together of Festival Ballet alumni, and in New York, Toronto and Los Angeles for dance community events.

Teaching students at the Scotiabank Dance Centre until a year before his death, Ian was a member of the board of directors of the Vancouver Ballet Society and, to the end, maintained active relationships with Moscow City Ballet, Vancouver’s Goh Ballet Academy and, of course, his beloved Kirov.

The years of drugs and booze, it could be argued, derailed a potentially brilliant career, and the commonplace comment would be that Ian “struggled with his demons” throughout a turbulent life. But in truth he didn’t so much struggle with them as he partied with and celebrated them.

During our Montreal years a big hit in the clubs was Laura Branigan’s “Self Control,” and Ian adopted the number as his theme song. He did indeed, everywhere he went and in every city he called home, live among the creatures of the night.

So when, if ever, is it appropriate to tell the full story of a man’s life, at least so far as space and word-counts will allow? To present the fuller and more honest picture and acknowledge that the less attractive side of a life is as important to the full measure of the man as his triumphs.

“Hit it honey!” Ian would have urged, another of his favourite phrases. Well, I guess I’ve hit it, haven’t I?

I’ll always remember Ian with great love and miss his company, especially when I’ve backslid and gone weedy.

Kevin Dale McKeown was Vancouver’s first out gay columnist, penning QQ Writes … Page 69 for the Georgia Straight through the early 1970s. His Still QQ column for Daily Xtra runs monthly on the last Thursday of the month. Contact him at stillqq@dailyxtra.com.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra