Janet Mock, Trish Salah, Jamie Berrout . . .

On the day that my first book came out, I felt like I was dying. For months after, my whole body ached with pain, deep in my muscles and the joints of my bones, for which my doctor could determine no physical cause. Reading and performing my work, once a source of vital energy and emotional validation, became an exercise in the excruciating. After every book launch, performance and public event, I would lie in bed for hours, unable to do anything but try to remember to breathe.

I laid there and wondered: Aren’t I living the dream, being a published trans woman of colour writer? Why does it hurt so much? And why do I feel so alone?

Gwen Benaway, jia qing wilson-yang, Vivek Shraya . . .

In continuing education for my work as a therapist, I recently learned that trauma psychologist Janina Fisher observes that for traumatized individuals, success often feels like shame — shame being not only the belief that one is an inherently bad person, but also the physical process of the body shutting down in response to stress. Shame is thus intrinsically linked with the chronic physical pain experienced by trauma survivors, a perspective also championed by renowned trauma physician Bessel van der Kolk.

I knew at once, with the clarity of suddenly seeing myself reflected in a mirror, that this is what was happening to me. I was ashamed of what I had spent my whole life dreaming of doing: becoming an author. And I knew intuitively that this shame was connected to the strange phenomenon of simultaneous public attention and private isolation that comes with being suddenly catapulted into the category of a (very, very minor) public figure.

Every cultural worker of “minority” identity is familiar with this phenomenon. Many professionals experience it as well. All of a sudden, you become an object of interest to the majority, which has so very many (well-intentioned, of course) questions:

Who are you? What are you? How did you get here? How did you get so smart, so articulate, so exceptional? Tell us what it’s like to be you. Can you help us become more diverse, more inclusive, more politically correct? (As long as it doesn’t make us uncomfortable.)

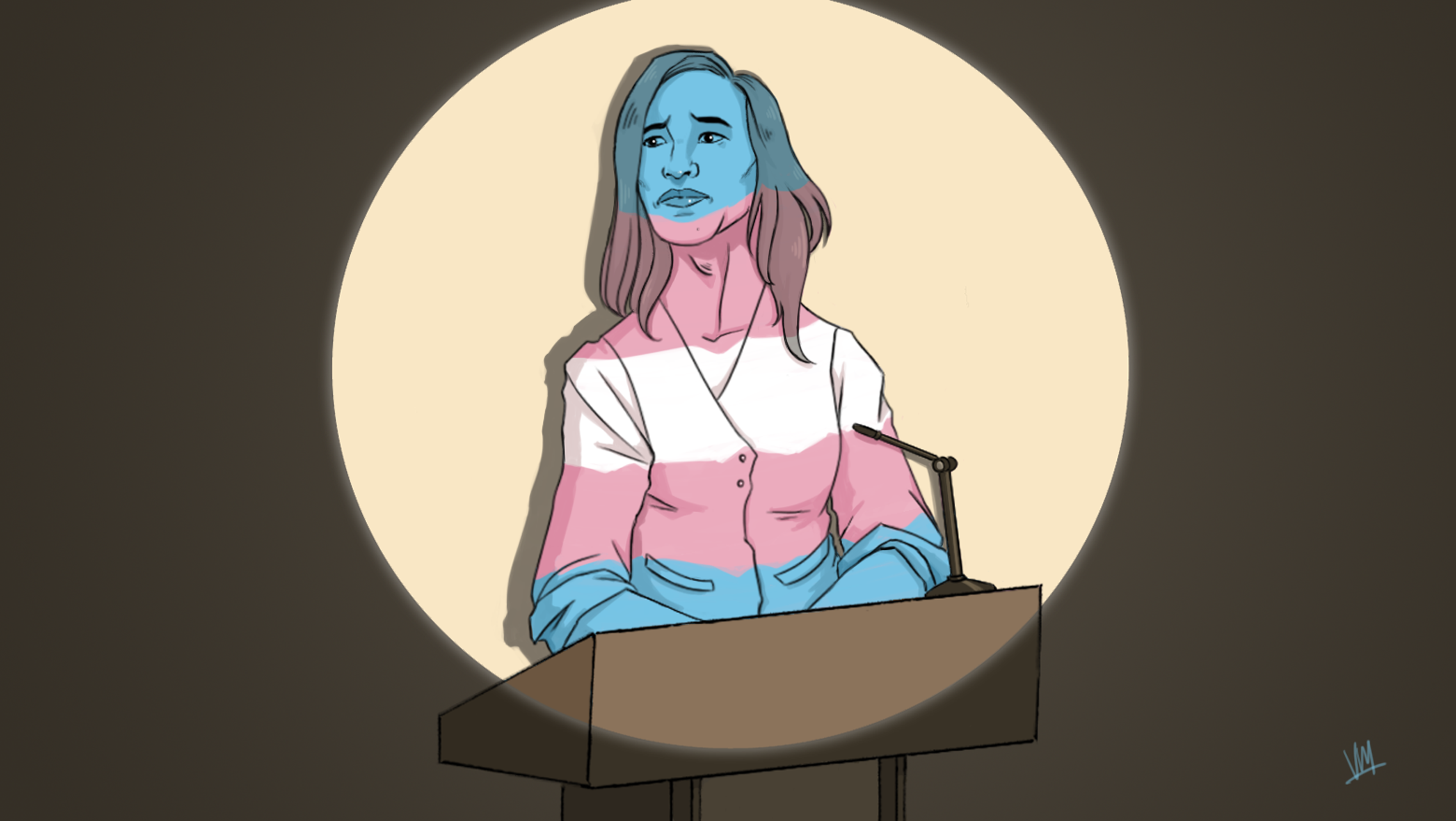

You’re given the impossible task of representing an entire community, which puts you in a tense, untenable position. Your body, your life story, your most intimate experiences are being consumed for the amusement and “education” of people who don’t share your struggle.

And you live in constant fear of failing to live up to the task of representation — of getting it wrong, of not being inclusive enough, of shaming your family and friends by saying the wrong thing or hitting the wrong political note.

The sad thing is, you never wanted to represent or educate anyone. You just wanted to tell stories.

Morgan Robyn Collado, Luna Merbruja, The Lady Chablis . . .

And having journeyed so far away from your community roots, you find it surprisingly difficult to return to your “own” people — to find the easy solidarity around money, sexuality, life — that used to exist between you and your sisters.

You’re different now, tainted as you are by newfound privilege, conditional though it may be. You’ve taken one of the few, coveted places at the table of the mainstream — by definition preventing a long line of others from receiving much-needed resources like money, security and acclaim.

What does it mean, for example, for me to accept a $500 expenses-paid speaking gig — usually the only one offered to a trans woman — at a festival or conference, when I know that many of my trans women of colour sisters are doing survival sex work at $60 per blow job? (Meanwhile, famous white cisgender authors are getting $3,000 for that same speaking gig.)

What does it mean to get on a plane every few weeks when you know people back in your hometown who have never left the same handful of neighbourhoods you grew up in? What does it mean to have your new books reviewed in Teen Vogue when you know that trans women of colour sex workers are being murdered on the regular, to resounding silence in the mainstream news?

Kama La Mackerel, Kim Ninkuru, D.T. . . .

Tokenism and queer celebrity culture are a process by which small-time queer and trans artists are pitted against each other to compete for meager resources and positions of false leadership. For artists, this usually looks like an unofficial quota of one of each kind of minority per show or institutional setting. I’m quite young in writing years, but I’ve already been to dozens of events — even LGBT-centric events — in which I was the only trans woman of colour paid to be there.

In fact, I have on several occasions been approached as a performing artist and speaker by event organizers and asked to “bid” — pitch my artistic services — and then never heard back, only to find out that another trans woman artist (usually a friend or acquaintance) has gotten the gig. As in, we were being tricked into competing against each other. Meanwhile, the event organizers in question got to choose between us — like choosing between fruit vendors for the “best deal” — and add a checkmark to their diversity checklist.

In her memoir Redefining Realness, Black trans advocate Janet Mock writes that being an “exceptional” member of a minority isn’t revolutionary, but lonely. That’s the thing about tokenism and queer celebrity culture: In the end, it’s about isolating us, turning us against each other, feeding into the myth that there can only be one special person — a single Chosen One to end all racial or gendered or transgender racial oppression.

Ryka Aoki, Kokumo Kinetic, Joshua Jennifer Espinoza . . .

So I am learning to let go of my shame and my loneliness. I am not alone. I am brilliant and powerful, and I deserve to be celebrated, and I am just one star in a vast galaxy of incredible trans femme of colour writers and artists living today. Some of their names are woven through this article, just like they are woven through my life. There are many more I do not yet know, many more on the way.

And we will rise together or not at all.

Kai Cheng Thom is a writer, performer, and social worker who divides her heart between Montreal and Toronto, unceded Indigenous territories. She is the author of the Lambda Award–nominated novel Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir (Metonymy Press), as well as the poetry collection a place called No Homeland (Arsenal Pulp Press).

UPDATE: This article has been update to remove the full name of one of the author’s mentioned in the story.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra