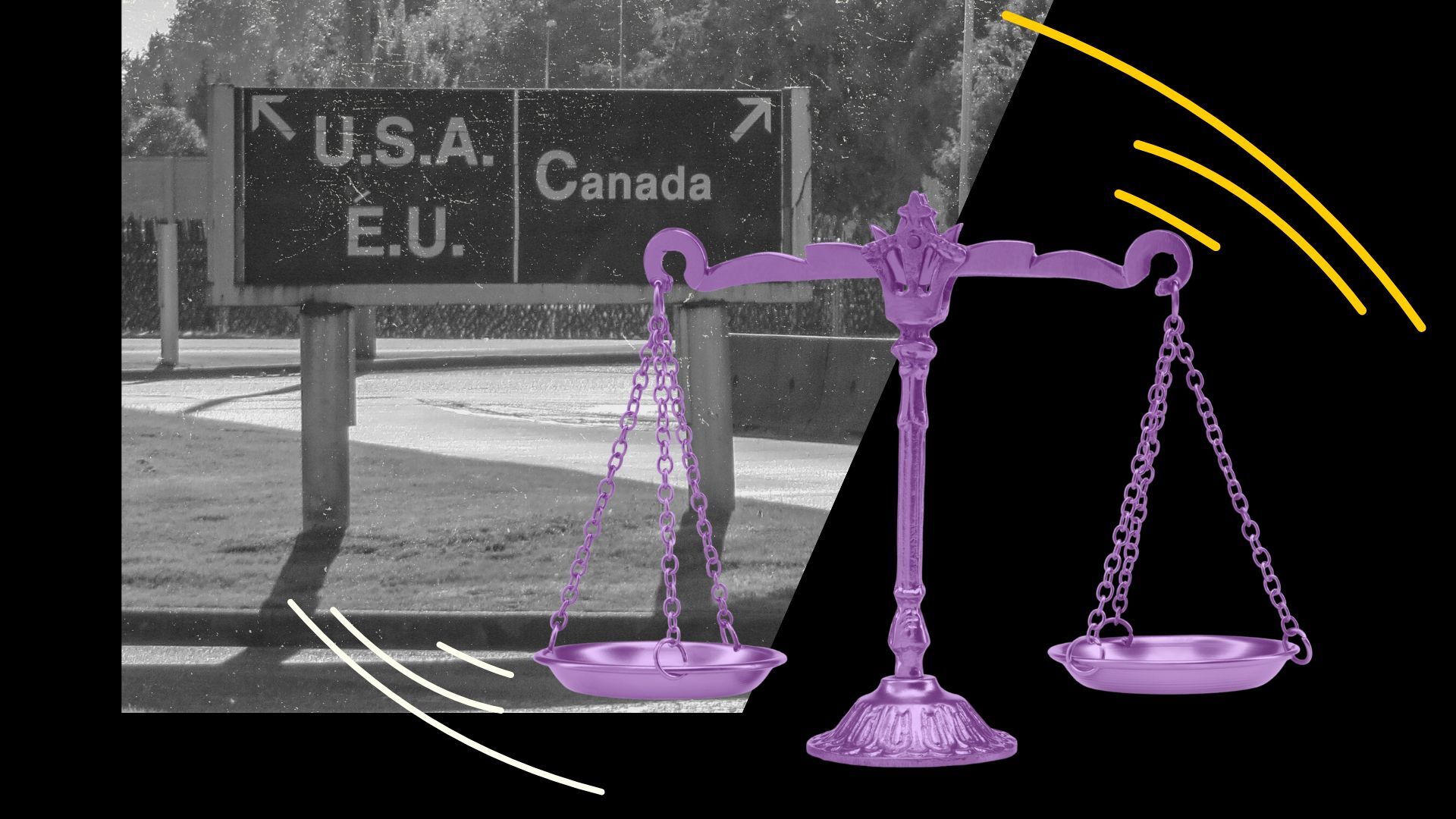

Earlier this month, Justice Julie Blackhawk of Canada’s Federal Court issued a stay order temporarily halting the deportation to the United States of Angel Jenkel, a non-binary American currently living in Canada. The ruling has been described as potentially precedent-setting, including by Xtra, because it took into account the recent wave of anti-queer policies enacted by the U.S. government since Donald Trump assumed the presidency in January.

But before we get too excited about this decision, it’s important to set a few things straight about how Canadian law works and what this ruling really means for trans and non-binary people seeking refuge in Canada from American laws and policies discriminating against them.

I am a graduate student in law at Osgoode Hall Law School of York University in Toronto. I also work as a student-at-law at Prison & Police Law, a Calgary-based boutique legal practice that specializes in assisting persons mistreated by the carceral justice system.

I have had a chance to review Blackhawk’s decision and to speak to one of the lawyers representing Jenkel. I don’t believe the decision is as precedent-setting as it might seem at first glance. Allow me to explain why.

Precedent explained

To start, let’s review the basic structure of Canada’s legal system.

Canadian law is a mix of legislation passed by governments and legal authorities established by judges. The latter is sometimes called “common law.” It is what people are talking about when they say that a particular decision sets a precedent.

When a court decides a case, it may set a precedent in one of two ways.

First, the court may set a binding precedent. This means that other courts have to decide cases with the same facts in the same way.

Or, second, the court may set a persuasive precedent. This is not a precedent as people usually understand the term. Rather, it means that other courts may take the decision into consideration when adjudicating future cases with similar facts, but do not need to follow it rigorously.

Importantly, precedent in Canadian law generally works hierarchically. If an appeals court in one jurisdiction makes a decision on some legal issue, lower courts in that same jurisdiction have to follow it.

Supreme Court decisions have to be followed in every jurisdiction; so when the Supreme Court says, for example, that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees equality under the law to trans people experiencing discrimination on the basis of their gender identity, that decision is binding on the justices in the federal and provincial courts across Canada

But when the Alberta Court of Appeal decides an issue, a court in, say, Saskatchewan is not obligated to decide that issue the same way.

In general, the higher a court is within the judicial hierarchy, the more persuasive its decisions will be for courts in other jurisdictions. So a Federal Court of Appeal decision is going to influence decisions by the Alberta or Ontario provincial courts more strongly than a lower Federal Court decision. That said, a Federal Court decision is usually going to strongly influence, and in many cases even bind, a subsequent decision made at the same level of court within the same jurisdiction; that is to say, it is likely to shape subsequent decisions on the same issues made by other Federal Court justices.

Jenkel’s case hasn’t set a precedent—yet

Blackhawk’s decision, issued in Ottawa on July 2, is a temporary one. It is meant to allow Jenkel to go through with a judicial review of their pre-removal risk assessment (or “PRRA”) application—a process that, in essence, asks a court to weigh in on the decision made in response to that application.

The PRRA is an application to stay in Canada on the grounds that deportation would expose a person to a risk of death or of cruel and unusual treatment or punishment.

Adrienne Smith is the founder and principal lawyer at Smith Immigration Law in Toronto. Together with Sarah Mikhail, she is acting as Jenkel’s legal counsel in their application for judicial review. Smith explains that Jenkel’s argument is that the PRRA officer who decided their application acted unreasonably by failing “to consider more recent country conditions in the U.S. with respect to the degradation of rights for the trans/non-binary community since President Trump took office in January 2025,” and requiring Jenkel to demonstrate “‘personalized’ evidence of risk” if deported.

In granting the deportation stay order earlier this month, Blackhawk found that the PRRA officer did, in fact, need to “consult up-to-date reports on country conditions” in the U.S., as Smith puts it; and the officer in Jenkel’s case acted unreasonably because they based their decision on information from before Trump’s inauguration, which did not account for “the change in conditions ‘for certain designated groups’ in the U.S. including trans/non-binary individuals.”

So what kind of precedent does this decision set? In Smith’s opinion, “the stay order is not precedent-setting … other than the fact that it is the first consideration by the Court of the evidence presented by an applicant that they face risks based on their trans/non-binary identity in the U.S.”

I agree.

Notably, Smith says, Jenkel “did not make a refugee claim in Canada based on their gender identity.” They submitted a PRRA application that cited a risk of being persecuted on the basis of their gender identity if removed to the U.S. It’s a distinction that matters because Blackhawk’s decision did not find that their PRRA application ought to be granted, still less that Jenkel should be afforded asylum on the basis of how they identify. Rather, Blackhawk found that the PRRA officer was required to consider “recent evidence of the conditions in the U.S. which may have supported a reasonable fear of persecution which was enough to meet the low legal threshold of being a ‘serious issue’ to stop the Applicant’s removal from Canada.”

The July 2 order is a narrow ruling that has more to do with facilitating access to justice than with upholding trans and non-binary rights. It has remarkably little to say to trans and non-binary Americans seeking refuge in Canada from Trump’s gender policies, except perhaps to clarify the kinds of information that PRRA officers need to take into account if they are to offer reasonable decisions in response to their applications to delay deportation.

This is not to say that Blackhawk’s decision doesn’t matter at all. At the very least, it offers a glimpse into how the justices on Canada’s Federal Court are thinking about American gender policies and their implications for immigration decisions. It may even prove somewhat persuasive for future judicial decision-makers trying to make sense of the legal implications of current events in the U.S. But a groundbreaking precedent opening Canada’s doors to trans and non-binary people fleeing American gender persecution has yet to come.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra