When we as LGBTQ2S+ people make demands of our government, the focus is often on public policy.

Outrage builds following Alberta’s recently tabled anti-trans legislation. Community members in Saskatchewan and New Brunswick rail against the government’s approach to queer and trans education. Pressure is put on the federal government to go further in their changes to blood-donation policies.

What’s less discussed is that our elected leaders don’t just control what we can and can’t do, but, in many cases, they also control where pink dollars flow. Though less headline-grabbing than marriage equality or banning conversion therapy, governments have for decades been moving numbers around spreadsheets—winning political points and showing their allyship t0 LGBTQ2S+ non-profit organizations by injecting public dollars alongside individual donations and corporate sponsorships.

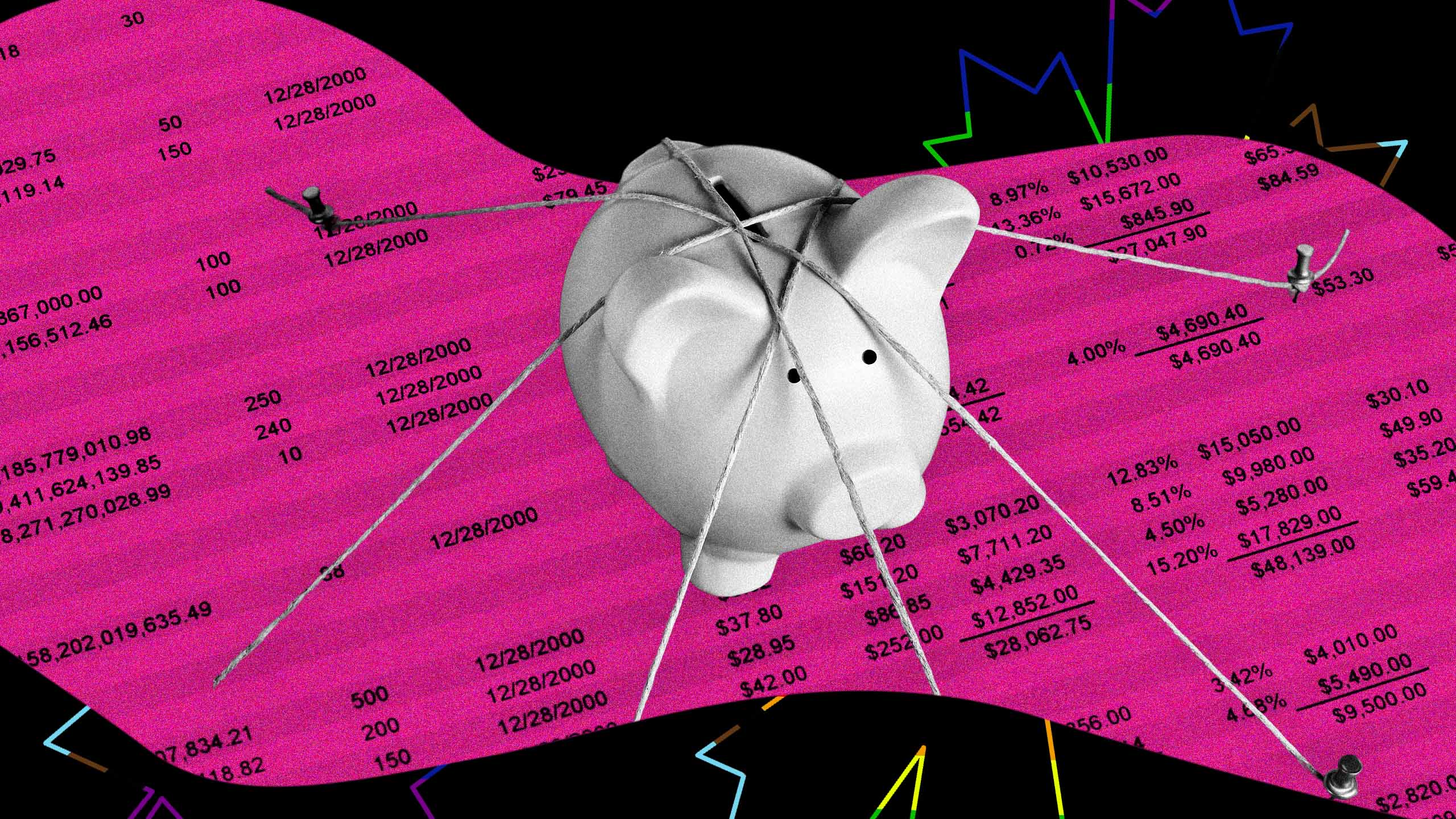

A review of publicly available annual reports and financial statements from more than a dozen large non-profits serving queer and trans people (whose revenues generally land in the millions) shows that federal funding accounted for at least 10 percent of all money coming in on the low end. Some organizations rely on the feds to cover as much as three-quarters or even 90 percent of their operating costs. On the federal front, these dollars typically come from Women and Gender Equality Canada—the government agency under which advancing LGBTQ2S+ causes falls—but also come from agencies related to public health, education, justice.

Think about the LGBTQ2S+ organization that handed you an HIV self-test, in part thanks to the nearly $18 million from the feds in 2022. Or the guest speaker on your college campus teaching your straight classmates about the trans experience—one of the first projects to receive money out of the current government’s $75 million 2SLGBTQI+

The dollars hit every region of the country, even on a smaller scale. In the past few months alone: $300,000 for the PEI Transgender Network, $453,000 for Quebec’s Fondation Émergence, $147,000 for Alberta’s Calgary Outlink.

These groups are the front line of care and support for LGBTQ2S+ Canadians, but with less than a year until another federal election must take place, they are bracing for a possible financial cliff. Over the past few months, every major polling firm has foretold a Conservative party win in Canada. While public opinion can sway, and next year’s election results are not inevitable, there is a strong chance Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre will be the next prime minister of Canada. Poilievre has yet to explicitly promise funding cuts to LGBTQ2S+ organizations, but he has committed to ending “wasteful” government spending and the “woke” approach.

“We know that our queer communities will face more cuts from different government agencies, and I think that’s scary,” says Sam Katz, director of philanthropy and communications at AIDS Committee of Toronto. “Just take a look at (Ontario Premier) Doug Ford’s government and what he did with autism funding—we know historically with Conservative governments come funding cuts to services, and having worked in this sector for almost 20 years, the experience has been that those cuts will come.”

Michael Kwag, executive director of the Community-Based Research Centre, a national non-profit focused on improving health for queer and trans people, is already looking for ways to make the organization less reliant on government funding. Last year, the organization’s revenue came almost exclusively from federal grants.

“We have to start diversifying, and what that means is carving out our space in the queer ecosystem—but a challenge for orgs like CBRC is that we aren’t doing a lot of front-line programming,” says Kwag, noting that the kinds of research and advocacy they do are very important, but not the most noticeable to the average person who may be considering donating to a LGBTQ2S+ non-profit. “We have to make sure our work is more well known even if it’s not the most visible.”

One approach is increasing the visibility of the work being done by queer and trans organizations. On Nov. 7, Pink Triangle Press, one of the world’s longest-running queer and trans media organizations and the publisher of Xtra, organized a Pink Awards celebration—the first of what it aims to make an annual event recognizing community contributions and changemakers in Canada.

“The purpose is to really highlight and amplify the stories of those unsung heroes on the front lines,” says David Walberg, PTP’s executive director and CEO. “We’re seeing queer issues dehumanized in the political landscape and agenda—and it’s our intention to turn that around and take back the narrative talking about real people, real organizations.”

The You Can Play Project, The 519 and 2-Spirited People of the 1st Nations and pflag Canada were among the non-profits recognized at the event by celebrities and activists including actor/producer Elliot Page, Schitt’s Creek’s Emily Hampshire and musicians Rufus Wainwright and Jeremy Dutcher. Though still reeling from the American election results that saw Donald Trump reclaim the White House earlier in the week, the people in the room rallied around hope, joy and the need for continued financial support of queer and trans charities.

Each organization honoured at the Pink Awards received a $5,000 donation, a spot in an advocacy media campaign and a portion of proceeds from a silent auction.

Speaking with Xtra, Page says he hopes the event continues to raise awareness and money for the types of organizations he wished he saw while growing up on Canada’s East Coast.

At the celebration, Page honoured Skipping Stone, a Calgary-based organization that works with gender-diverse people.

“These people and organizations are on the ground doing a lot of heavy lifting for our community and offering crucial support and education—saving lives and allowing people to thrive.”

Even if organizations are able to get the attention of everyday donors, it still may not be enough.

For the 11th year running, the number of Canadians making charitable donations has declined, according to a CanadaHelps 2024 report. Meanwhile, one in five Canadians say they relied on a charity for support last year—with nearly 70 percent of them doing so for the first time.

“We have seen the largest drop in our fundraising in the individual giving category,” says Lauren Pragg, executive director of the LGBT YouthLine, which saw individual donations drop from more than $400,000 to about $187,00 between the fiscal years 2022 and 2023. “It makes it really hard for us to plan, when we compare that number to the last few years, it has really diminished.”

Pragg says it has impacted every aspect of the organization—from its ability to keep the doors open all the way down to how many summer interns it is able to hire.

“We have to pay our staff, give them benefits, pay for technology and cybersecurity and all these things. They’re not very exciting, but these are things we need, and with the drop in individual giving, which is very flexible funding for us, it can really tie our hands.”

The need has played out in real-time several times over the last year alone. Last month, the Canadian Centre for Gender and Sexual Diversity announced that, after 19 years of programming for schools and queer youth, they are bankrupt and no longer able to operate. This summer, Canada’s longest-running queer bookstore, Glad Day Bookshop, and the non-profit it operates, posted an emergency fundraiser to halt their eviction. Last year, the same was true for the quarter-century-old Action Santé Travesti(e)s et Transsexuel(le)s du Québec in Montreal, an organization working to improve the lives of trans people.

“That is a canary in the coal mine,” says Aniska Ali, philanthropy director of Toronto’s The 519 community centre. “We are seeing organizations crumble because the need is just so huge that the funding available cannot support it.”

Ali says that while there is a lot of support for the types of programs The 519 runs—immigration assistance for queer and trans people, legal services, food and housing programs—the money comes from people who themselves are struggling. “We know that queer and trans folks are overrepresented in low-income households, in employment and housing precarity. So that means the folks who are the most committed to making sure this space continues to exist are the folks who may have the least amount of resources to give.”

Governments and individual donors are two potential sources of money. The third is the private sector, but many queer and trans non-profits are skeptical of treating corporations as a financial lifeboat.

“We have not really played in the corporate sponsorship game generally, and there are definitely drawbacks,” says CBRC’s Kwag. “We have to be mindful of the ethics of deepening our relationship with corporate partners, being aware of our values and principles, which are most directly about queer, trans and Two-Spirit people, but are also connected to broader social movements and issues that these communities care about.”

Kwag gives the example of a corporation that opens up money for LGBTQ2S+ organizations but is regressive on issues such as climate justice or truth and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. A partnership with that corporation has the potential of undoing years worth work done by the non-profit.

“It is an issue queer non-profits have to face right now. There are protests around Prides being too reliant on corporate sponsorships.”

With these pitfalls in mind, individual donors are becoming even more crucial. As for how to attract more of those donors, a few approaches are being taken.

One strategy for engaging more donors is getting innovative with new ways to incentivize giving.

“Gen Z and even millennials aren’t really concerned with tax receipts,” says Katz, who in addition to leading ACT’s fundraising strategies, also advises other non-profits about ways of earning financial support. Katz is helping ACT set up an “impact store” where people can buy stickers and other merchandise with proceeds going back to the organization. “Today’s younger donors, they’re more concerned about getting an experience or product in return for that donation.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra