After 16 months of fighting provincial Conservative efforts to roll back protections for trans and gender-diverse youth, the Liberal election victory in New Brunswick on Oct. 21 may provide activists a bit of relief.

“We’re exhausted,” says Nicki Lyons-MacFarlane, an activist with Imprint Youth, a community organization serving gender-diverse children and young adults in Fredericton. “We’ve been fighting for the rights of our queer and trans kids for the last year and a half.”

Tasia Alexopoulos, an NB-based spokesperson for the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada, has been fighting to protect reproductive rights in that province for over a decade. The two struggles are very much related, she says.

“They’re very much connected,” she says. “Similar stakeholders, and very much in common … this is a very anxiety-inducing time for children who are experiencing gender in a different way and are scared.”

New Brunswick is where the most recent wave of legislative attacks on queer and trans kids began—when former Conservative Premier Blaine Higgs began the process of revising provincial education policy to remove protections for those students. While New Brunswick rolled back existing protections, conservative and right-wing governments in Saskatchewan and Alberta followed suit by introducing new restrictions on rights of gender-diverse youth, with Alberta’s premier also targeting trans women’s access to sports and healthcare for gender-diverse youth. Quebec is in the process of reviewing its policies (with no involvement of trans or LGBTQ2S+ community members in that process) and Ontario’s government signalled support for Saskatchewan’s and Alberta’s policies while stopping short of committing to follow suit. It’s become a hot issue in the British Columbia election as well, with provincial Conservatives threatening to remove Sexual Orientation Gender Identity (SOGI 123) teaching resources provided to teachers in that province.

Lyons-MacFarlane says they’ve organized more protests and rallies since the changes than they can count. As schools became unsafe for gender-diverse youth, Imprint Youth expanded services to fill the gap. Their once-monthly programs are now offered weekly, and they’re struggling to meet the demand. But their volunteer base has also exploded, with parents and community members offering to help expand capacity for programs.

“These kids that are coming to our programs now need that support, they need that space where they can feel calm and feel a sense of family and community,” says Lyons-MacFarlane. “That’s one beautiful thing that has come out of the last 16 months. But … there are nights where I don’t know if I can keep doing this anymore, because the last 16 months have been nothing but fighting back against these changes and this misinformation and rhetoric.”

They say it’s been a triggering, emotional train ride, but that’s given them extra drive to pour into their activism.

They recall returning home from work one day in August and finding anti-trans flyers in their mailbox, part of a campaign by Campaign Life Coalition, during which two Canada Post employees were suspended for refusing to deliver the coalition’s materials.

“It was like a punch in the gut,” Lyons-MacFarlane recalls. “Like holy shit, is this real, is this actually happening here?”

What hit them even harder, they say, was the reaction of trans kids they work with—some children were deeply traumatized by finding the flyers on their doorstep when they got home from school. Some children and families were so angered by the campaign they destroyed the offensive material in community bonfires.

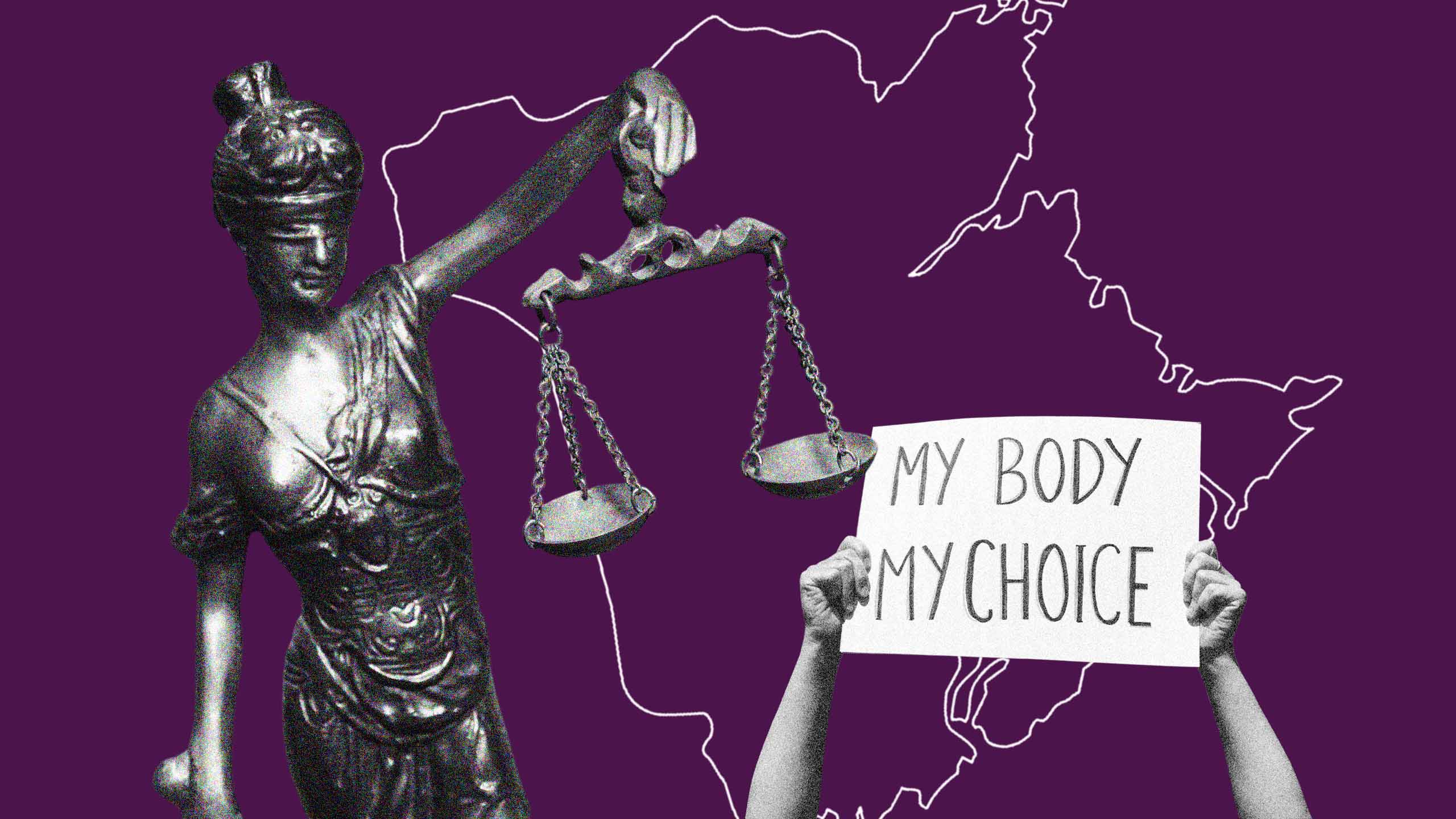

It’s no coincidence that the flyers were distributed by Campaign Life Coalition; the Canadian right-wing organization is best known for its anti-abortion work—and both abortion and gender identity are issues of bodily autonomy. As human rights protections and supports for trans, gender-diverse and queer people have inched their way into legislation over the past four decades, far-right and conservative advocacy groups have expanded their ambit from controlling women’s bodies through anti-abortion and anti-reproductive rights campaigns, to controlling sexuality and gender identity more broadly.

Alexopoulos says the leaflets brought home to a lot of activists the scale of their fight.

“I think when that landed in people’s mailboxes, they realized—this is serious,” she said. “This was a serious and well-organized attack. And I think that really, really scared people. Suddenly people saw that this was big, this was happening. It put a lot of people in a really uncomfortable and scared position.”

Sarah Worthman is co-founder of the No Space For Hate Movement, which began in Newfoundland and Labrador.

“We need to recognize that it’s not going to stop with queer and trans people,” she says. “It’s not going to stop with abortion rights. It’s really about maintaining dynamics of privilege and stripping back the rights of people.”

In New Brunswick, notes Lyons-MacFarlane, the campaign against sexuality and gender protections in schools has taken centre stage in part because far-right groups have been so successful in making abortion less accessible in that province.

“In New Brunswick, there’s really nothing for [anti-abortion activists] to fight anymore. We’ve lost access to the Morgentaler Clinic, that’s shut down. Clinic 554 is shut down. So they’ve front-lined that energy into the anti-trans movement.”

Alexopoulos disagrees with the framing of an anti-abortion victory in that province—while private clinics have closed, abortions are still available through provincial public hospitals, and the fight is still very much alive, she says.

But she acknowledges the links between anti-reproductive rights activism and anti-queer and -trans activism.

“Whether it’s abortion or whether it’s about trying to control trans kids, or sexuality and gender in general, it’s all about control,” she explains. “They’re all very authoritarian, and what they’re looking at now is controlling children. And when we look at the anti-abortion movement, it’s very much about control.”

Alexopoulos lives and works in Sackville, a university town of 6,000 in southeastern New Brunswick. Last September she was shocked to witness the town’s annual Fall Fair targeted for protests by right-wing activists.

“They targeted Sackville because they said we are too woke of a community,” she recalls. A counter-protest was organized, which brought out about 100 supporters against the far-right’s two dozen.

“We had Pride flags and bubbles and a big rainbow cake and chalk drawings taking up the space, and they had signs about gender and cashless societies and ‘Fuck Trudeau.’”

The right-wing protesters may have been outnumbered in Sackville, but Alexopoulos warns that it takes more than numbers to fight back against the impact of disinformation. She helped organize a counter-protest against the annual “Life Chain,” an anti-abortion protest organized by Campaign Life Coalition in early October. What shocked her most, she says, was hearing mainstream journalists asking questions based on right-wing disinformation campaigns.

“I had a reporter ask me: ‘What about late-term abortions at nine months?’ And I said ‘That doesn’t happen.’ But it’s such a piece of misinformation that’s really swirling right now, and we can trace that directly to what’s happening in the United States.”

The failure of American media to effectively counter disinformation means it spreads to Canada as well, she warns. Once circulating here, it emboldens the right-wing in this country to spread further disinformation and expand their political agenda.

The Liberal victory has changed the province’s political landscape, but it’s too soon to say how much. The party made vague promises to expand abortion access, and also to roll back changes to the education policies affecting gender-diverse kids in schools. Alexopoulos wasn’t impressed by the party’s lack of specific commitments.

“In this provincial election we have not had deep discussions about reproductive justice, and the conversations we’ve had about gender have been very superficial,” she says.

But there’s a sense of relief that the Conservatives are out of office, and former premier Higgs lost his own seat. National organizations like Queer Momentum have celebrated the Conservative loss as a sign that attacks on trans and gender-diverse people aren’t popular. It remains to be seen how much will actually change.

“I always feel a mix of terrified and very hopeful,” says Alexopoulos. “This work is never static, these rights are never static.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra