Earlier this year, when I reported on what it’s like to be a young trans person in Canada, I got the chance to do something few newsrooms take the time to do: actually speak with trans kids about their lives. The bills, policies and laws targeting trans youth that are being introduced across Canada and the U.S. have been covered extensively in recent years. But that reporting doesn’t always include the perspectives of the youth and their families who are affected by these repressive rules.

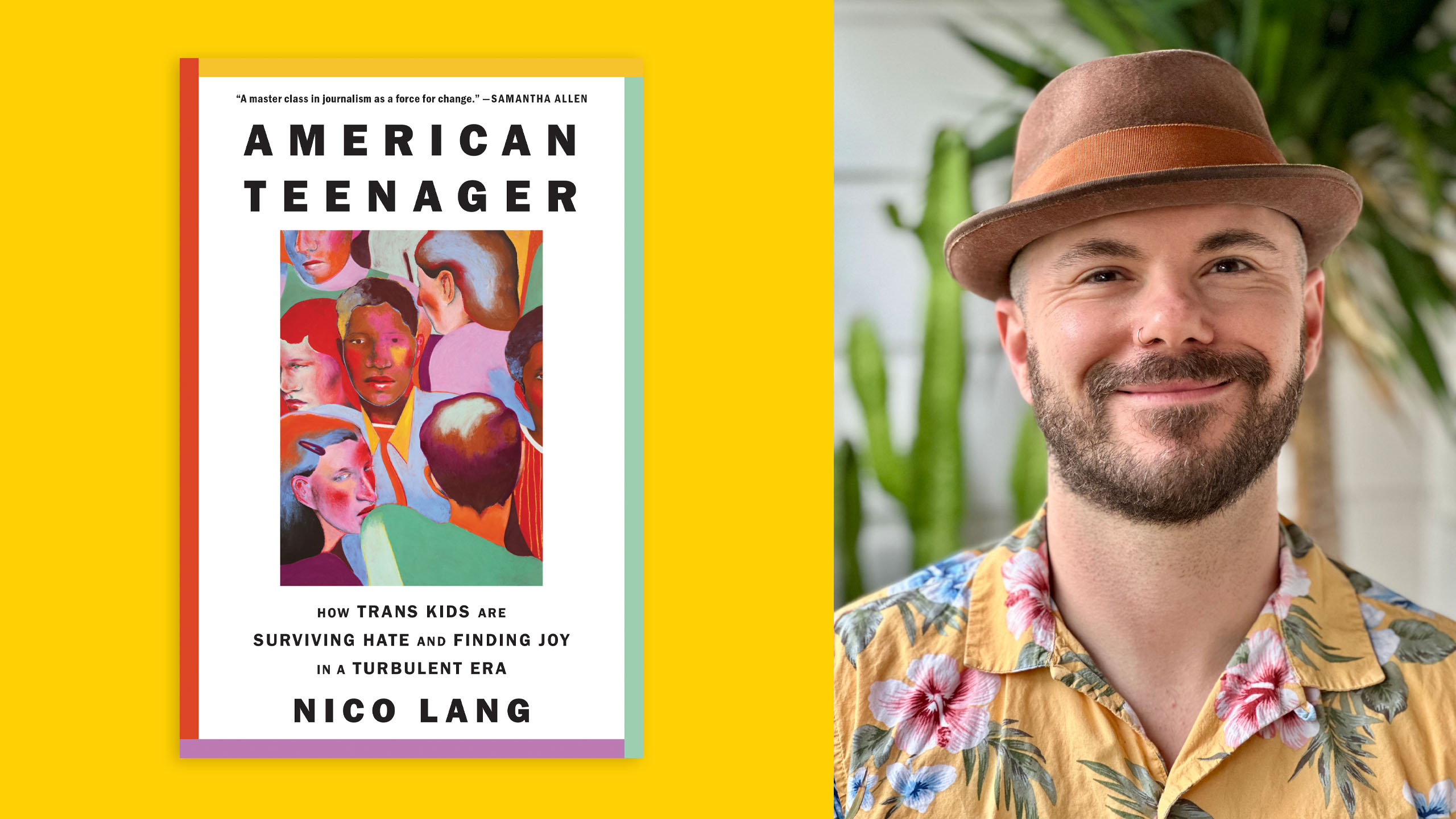

In their new book, American Teenager: How Trans Kids Are Surviving Hate and Finding Joy in a Turbulent Era, author—and Xtra contributor—Nico Lang meets this problem head-on, by letting their sources speak for themselves. Lang spent close to a year travelling across the U.S. in order to profile seven families of trans youth in different states. Throughout the book, we hear from kids with a range of experiences and perspectives: there’s a Texan high schooler who is falling in love for the first time, a teen in Florida who has just been stripped of her access to hormone replacement therapy, a kid who is looking for the perfect prom suit, a young woman who wants to become a makeup artist (or maybe a marine biologist, she still hasn’t quite decided yet).

As a journalist, Lang has been reporting on the lives of trans youth and their families for years, and they’ve brought their usual candour, compassion and nuance to the stories in this book. The result is a touching and intimate view into the lives of trans youth in a country that is sorely failing to help them thrive. There’s no one monolithic trans experience, Lang knows—and their book helps readers see that.

Xtra spoke with Lang about their cross-country trips, what supports kids really need and why telling a broad range of stories is so important.

What made you want to focus on trans youth specifically?

I knew so many families of trans kids already from my previous reporting. I had this trust built in. So it just made sense to do this book. If you look at the political environment in the U.S. right now, more than 650 bills targeting trans people have been introduced this year across the country. The vast majority target trans youth. And that story still hasn’t really been told to the depth that it should—not just the story of the bills themselves but about the real impact that they have on people’s lives. How people are affected in their own communities while their own government is trying to erase them and force them back into the closet.

At the same time, when journalists get to tell the stories of trans youth, the stories are almost always tied to anti-trans legislation in some way. I really wanted trans kids to be able to speak for themselves. Rather than a book about these horrible bills and horrible laws, it’s about these kids and the way that they see the world. So often we don’t hear from trans kids directly at all. But in this book we’re hearing about what they want to do with their lives, about their dreams and aspirations—and also mundane stuff like their likes, their dislikes, the annoying kids at school. Cis kids have gotten the chance to talk about that kind of thing for ages—there’s an entire tradition of teen movies that are about all of this stuff. Trans kids have never really gotten that opportunity.

One thing that really stuck out for me—as someone who has also written about trans youth—is that this book doesn’t just focus on the difficult aspects of being young and trans. It also focuses on the joy and mundanity of young people’s lives. When I met kids during my own reporting, they often didn’t even really want to talk about being trans—they wanted to talk about, like, their favourite video games and the drama they have with their friends. It seems like the same thing happened to you. Why did you want to include that kind of stuff?

Many years ago, celebrities would say things in interviews like, “Being queer is the least interesting thing about me.” And I do think it’s true that being queer or trans can be the least interesting thing for some people.

For these kids, I do actually think being trans is important because it dictates how many of them are treated by their state lawmakers. So we should talk about that mistreatment. But it’s certainly not the only thing to discuss. With trans kids we sometimes act as if transness is the only topic of conversation that we could even have—that we as two humans couldn’t connect about anything else other than the fact that they are trans. It just gets boring to talk about the same thing over and over again. These kids get bored with it. They just don’t want to talk about being trans anymore.

You profile families in a bunch of different geographic locations. They have very different histories, racial backgrounds, socio-economic statuses. Why did you seek out such a wide breadth of stories?

I didn’t want to write the same story seven times. I never wanted the reader to get to a point where they felt they’d figured it all out. If you stopped reading halfway through the book, you wouldn’t hear from Ruby, a trans girl from Texas who’s been very supported by her family and in her church environment. She recently fell in love with this boyfriend and we get to watch them have a story that is lovely and warm and affectionate. You would miss Clint’s chapter, which is the story of this incredible Muslim Pakistani family who have continued to support their trans kid as he’s carving out his own space and his own identity. Then we hear from a family dealing with homelessness, and Jack, who is the daughter there being de-transitioned by the state of Florida because they won’t give her access to the hormones she’d previously been taking. These are all stories we rarely hear.

If we keep limiting the kinds of stories we tell, we’re limiting the representation that’s out there. We’re limiting the voices that are out there. And I just wanted as many kinds of perspectives, as many kinds of stories, in this book as possible.

I know you’ve been writing about trans youth for many years now. Did you learn anything during this book that surprised you?

Jack’s chapter was one of the more eye-opening chapters for me. When we meet her, Jack has lost her gender-affirming medical care after the state of Florida decided trans youth could no longer access medical coverage through Medicaid. Luckily, Jack was five months away from turning 18 and being able to access that care again. But when you’re being forcibly detransitioned by the state, five months is a really, really, really long time.

We know on an intellectual level that this kind of thing happens, but we rarely hear from the people being forcibly detransitioned themselves. Jack’s story really illustrates the depths of what we are doing, not to trans people, but to children. This is a 17-year-old girl who went through this, who had her own body taken away from her. She described it as being like a real-life [David] Cronenberg film. That should never happen to anyone, and it should especially not happen to a child.

From my own reporting I know that there are a bunch of auxiliary challenges that come up for trans youth when bills limiting their rights get introduced. Even the kids who are the most supported at home still face bullying and depression and the existential dread that comes with having their rights targeted. And they are suffering! Why is that important for people to understand?

You can see this the most in Ruby’s chapter. She’s a teenager in Texas who is loved and supported by her entire family and her religious community and her boyfriend. But even though Ruby is incredibly fortunate and kind of has everything going for her, she still can’t continue to live in Texas because there’s no future for her there; that your state has tried to take away away your right to gender-affirming care, your right to play on a sports team that aligns with your identity, to use the bathroom at school, to learn about the LGBTQ2S+ community in schools or to have a driver’s licence or birth certificate that aligns with your identity. Your community can support you all they want. They can love you all they want, but they can’t change state policy, right?

What do people get most wrong about trans youth?

That they forget they’re just kids. We seem to forget that somehow. When it comes to trans kids, because of the ways in which they’re dehumanized and exploited by our current political system they’re, like, made into these monsters, or kind of dismissed outright. Republicans will refer to them as “gender-confused children.” That’s not only incredibly dismissive, it’s also dehumanizing. Because they’re not saying that they’re children first. It’s the “gender-confused” part that comes first.

I don’t know how we get out of this. That’s sort of one of the questions I tried to explore in the book. We’re stuck in this horrible political cycle of silencing and erasing children. Like, how do we stop doing that? And I don’t know if there’s a clear answer to that, necessarily. I think it starts by just listening to these kids, hearing what they say and affirming them as being a whole person.

I just hope that reading a book like this reminds people not to just make projections about such a large group of people. If you want to know what a trans kid is like, or what a trans person is going through, just ask what any human going through, because they’re probably going through all the same stuff. But then you just add all of this horrible anti-trans rhetoric on top of that, and that makes that burden a little bit harder. They’re a person, right? But they just happen to be a person wearing a really heavy backpack. And if we are interested at all in making the world better for trans people, we just need to help them take that backpack off.

And why do you think there’s such intense scrutiny on these youth right now?

I think it gets down to the ways in which people really dismiss and discredit kids in general. We like to tell all children: you’re too young to know who you are. You’re too young to make decisions about yourself and your life.

And it’s weird, because we expect kids to know so much already. When you’re applying to college, you have to know what you’re going to do with the rest of your life, but somehow, like, you can’t know that you’re trans already?

And even young kids have, I think, way more self-knowledge and self-awareness than we give them credit for.

The kids I spoke to in the book are confused about so much—because life is confusing when you’re, like, 16! They’re asking questions like, what kind of job should I have? What college should I go to? What friends should I have? But the thing is, none of them are confused about being trans. It’s the one thing that they all seem to know and hold dear—that they know who they are. It’s just a matter of getting all the other ducks in a row, and that work isn’t really made easier if there are lawmakers out there who are making it more and more difficult for them to be the people that they know themselves to be.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra