We are less than a week away from the coronation of King Charles III, and a lot of attention is being focused on not only the events, but all of the leaders of Commonwealth countries coming together for the event. As Charles takes over as the head of the Commonwealth, there is a lot to do when it comes to seeing this group of nations—most, but not all former British colonies—live up to the commitments they made around issues like LGBTQ+ rights. Canada can and should take a more active leadership role when it comes to pushing for these changes.

In 2013, the Charter of the Commonwealth was signed, which obligated member states to live up to the obligations of shared values in 16 categories, including democracy, human rights, international peace and security, freedom of expression, separation of powers, rule of law and gender equality, to name a few. Canada had a prominent role in developing this Charter in a process known as the Eminent Persons Report. Former Conservative senator Hugh Segal was a key player in compiling that report over 14 months, and it was delivered to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Perth, Australia, in 2011.

At the time the Charter was signed, the Commonwealth was composed of 54 countries, of which 41 still had laws on their books outlawing homosexuality. More than a decade later, two more countries have joined the Commonwealth (who were not former British colonies), and the number of countries that outlaw homosexuality has fallen to 35, and of those, 20 are considered to be countries that don’t enforce those laws, but there has been backsliding. In Ghana, President Nana Akufo-Addo recently told U.S. vice-president Kamala Harris that “substantial elements” of that country’s draconian anti-LGBTQ+ bill has been “modified” by his government. More recently has been the legislation in Uganda, though that bill has not yet passed as President Yoweri Museveni has sent the bill back for reconsideration—but not because he disagreed with its contents, but rather because he thinks it should include provisions for conversion therapy.

While Canada has engaged diplomatically, including with other Commonwealth countries, on trying to dissuade Uganda from going down this route, we are also working the channels of parliamentary diplomacy. This is less formal and not at the leader-to-leader level, but rather it has parliamentarians engaging with each other on a peer-to-peer level, and they are pushing on LGBTQ+ issues.

“It’s very much on the agenda because the next Commonwealth Parliamentary conference is in Accra, Ghana, at the end of September,” says Liberal MP Alexandra Mendès (Brossard—Saint-Lambert), the chair of the Canadian Branch of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. “It has given rise to quite a few questions.”

Mendès notes that because the meeting is at a time when the House of Commons is sitting, it’s doubtful that any MPs will be allowed to attend; however, the debate is whether or not to send a delegation of senators, or to make a stand because of Ghana’s backsliding on the Commonwealth Charter.

“Is our absence going to be considered consent, or should we go to make our point, and get as many allies as possible to bring the issue to the floor and get it discussed at the general assembly?” Mendès asks. “That’s what we’re discussing right now.”

Mendès says that the U.K., in particular, is shocked that Ghana went ahead with their bill, and that Uganda is following in their footsteps, though the U.K. approach is to be at the meeting to make their voices heard. She also points out Kenya and South Africa are two countries who have been making their “discomfort” with the Ghana and Uganda bills known.

She notes that any resolution made by the Parliamentary Association wouldn’t have any enforcement capacity, because that kind of intervention has to come from the high-level Commonwealth organization, and to come up at the next CHOGM, which will be held in Samoa in 2024, and where King Charles will be in attendance.

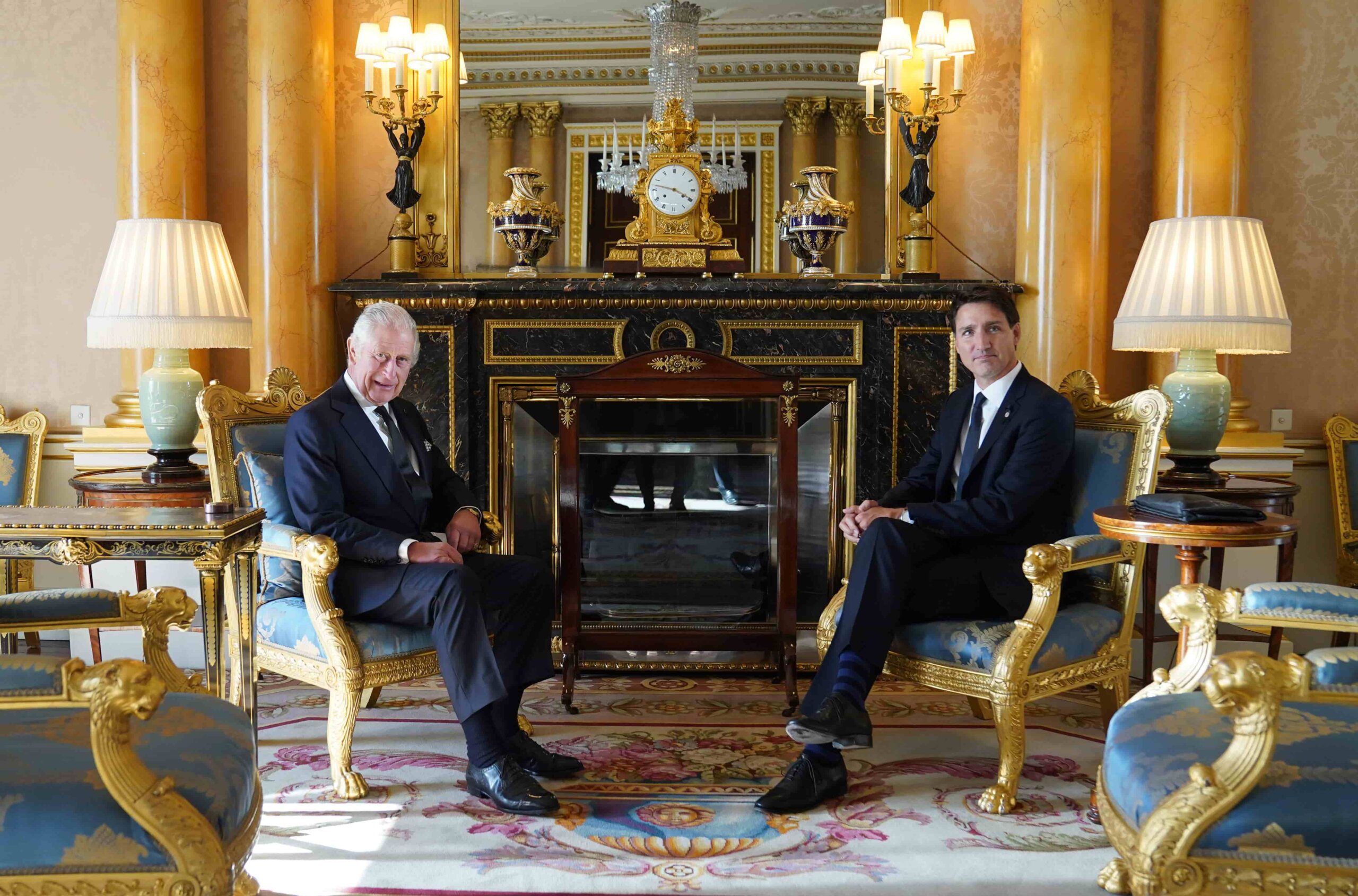

And this is where I think Canada’s opportunity lies. We played a big role under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney in bringing down apartheid through the Commonwealth, in part by getting the Queen on side, where she could exert some subtle, soft power in getting other nations on board with Canada’s sanctions plan. That was instrumental in putting U.K. prime minister Margaret Thatcher in a corner and forcing her to join in the sanctions where she had been reluctant to. Can we replicate this success in pushing more Commonwealth countries into coming in line with the Charter, and in pushing Ghana and Uganda to abandon their anti-gay bills?

Justin Trudeau still has some international cachet left—possibly more than he has domestically—and the Commonwealth is in a moment of generational change with the transition of the Crown to Charles. The Commonwealth was known to be risk-averse, particularly in pushing its members, but perhaps Charles can help foster a bit more movement on these issues, particularly if it’s done at the behest of his prime ministers from countries like Canada, the U.K., New Zealand and Australia. And it’s at places like the upcoming coronation where Trudeau can work to build these alliances on the road to the next CHOGM, where they can apply that political pressure.

Canada can also do more with supporting the Commonwealth Equality Network (TCEN) and the Kaleidoscope Trust, which runs TCEN’s secretariat. While Canada’s foreign aid funding is meagre under the current budget, if we want to take a stand as part of the coronation, we could announce more funding or support for TCEN and the Kaleidoscope Trust as some kind of coronation project or donation in lieu of a gift, and make a statement about generational change and turning the page to an era of equality for everyone in the Commonwealth, queer and trans people most especially. We have a platform within the Commonwealth, and we should be using it while there’s a spotlight.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra