Black people are the pioneers of many art mediums—and we often don’t get flowers for our accomplishments. Whether it be the Black man on a horse featured in the first motion picture in 1878 or the pioneers of rock ’n’ roll, Black people have made landmark contributions to the forms of entertainment we know and love today.

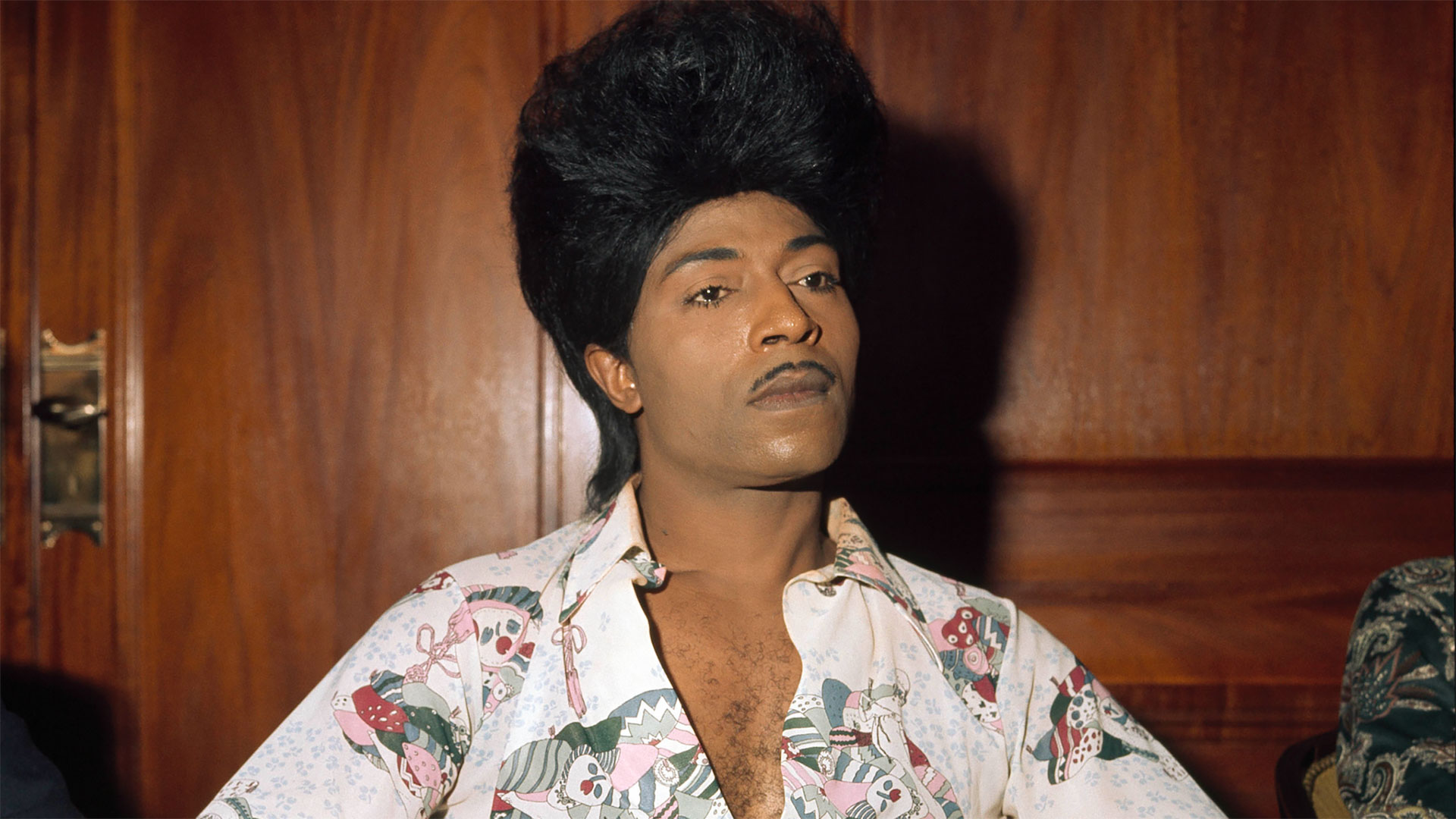

This sentiment could not be exemplified better than through the career of legendary Richard Wayne Penniman—aka Little Richard—the Black queer trailblazer who shaped rock ’n’ roll and had to wait so long into his life to get recognition for doing so. Lisa Cortés’s latest documentary for CNN Films and HBO MAX, Little Richard: I Am Everything, which premiered at Sundance last month and will release in April, pays tribute to the late artist and explores the impact he had on the music industry along with the LGBTQ2S+ community as one of the first rock stars in music history. As Billy Porter says in a talking-head interview: “Sorry, Elvis.”

I Am Everything chronicles Little Richard’s life and career, told primarily through his own words via beautifully restored archival interviews he gave throughout his life. Cortés seamlessly threads the footage into a fascinating and complex life story, along with talking-head interviews by Black historians, scholars, surviving family members, neighbours and musicians who toured with Little Richard, including Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney, who both get flustered while expressing how magical it was for them to meet Little Richard, and describe him as both an inspiration and the architect of their genre.

Growing up in Macon, Georgia, in a church family of 12, Little Richard always stood out from the bunch. In his physicality, he was born disabled, with one arm and leg being shorter than the other. From a young age, he was always passionate about music, specifically the tunes of gospel singer and early rock ’n’ roll star Sister Rosetta Tharpe. In 1947, Tharpe heard then-teenaged Little Richard sing one of her songs before she took the stage at his hometown performance centre, Macon City Auditorium. Tharpe was so impressed that she hired him to open for her in what became his first gig.

In the following year, after his father figured out Little Richard was gay, he kicked him out of his family home. Already blessed with a rich voice, Little Richard set out and performed in various venues in different genres of music. He began touring in the South with bands and performing in drag and had a drag stage name: Princess Lavonne. Throughout his early years, Penniman performed with many fellow Black gay pioneers of music including Ma Rainey and Billy Wright––who helped him get his first record contract. Need I remind you this is all during the 1940s and ’50s?

When his star power began rising, Little Richard was often warned about his appearance by his peers. A Black queer musician in drag was too abrasive for anyone to accept. But instead of conforming, he lived authentically. To paraphrase one of his sayings, he never accepted the idea that he had to be guided by some pattern or blueprint.

When Cortés incorporates footage of Little Richard’s performances, which are few and far between, it beautifully captures the electricity he conducted when performing onstage. The blissful unapologetic freedom he exhibited in his high-octave voice, and his quickness on the piano, are mesmerizing. Where more moments of concert footage can be interlaced, Cortés sometimes goes for a bizarre angle, to varying degrees of success. Black contemporary singers such as Cory Henry and Valerie June come on screen and sing a cover of a song that influenced Little Richard or something from his catalogue while shimmering dust particles representing Little Richard’s spirit surround them. It’s an endearing concept, but arrives awkwardly.

Cortés is mostly focused on exploring the difficulties that came with living and performing as a Black man during the Jim Crow era. The tidbits and stories Little Richard and his former bandmates share about their lives on the road and the little pay they got for his iconic music illustrate just how intense and frustrating it was for them to navigate a racist and discriminatory industry. The film even puts white singers like Elvis—but mostly conservative appropriator Pat Boone—on blast for doing vanilla-ass covers of Little Richard’s high-spirited songs, and they play like seeing your white friend cooking chicken without using any sauce.

I Am Everything hits best when expressing how despite the importance and impact this Black queer artist had on the industry, it took so long for him to receive any form of recognition in white spaces. The doc makes you wince with the footage of Little Richard presenting at multiple award shows like the Grammys, pouring his heart and pain onstage about not receiving a Grammy, despite the impact he had on the genre he shaped, and the audience nervously taking it as a joke.

Ask any millennial and they’ll probably admit that their introduction to Little Richard would less be MTV, due to them not playing Black artists in their heyday, and more his boppy, upbeat cover of “Rubber Duckie” on Sesame Street (which this film disappointingly didn’t even feature). This is an HBO MAX doc; they own Sesame Street. They could’ve thrown us a bone.

The film hits the familiar beats of many music documentaries where the artist has troubles with drugs, religion and sexuality, but the conversation of religious trauma is not taken to its fullest extent. Well into the later half, the doc brings up Little Richard’s inner turmoil between being his true authentic queer self, but also projecting a religious, God-fearing soul. It suggests an enticing underlying study of a tortured queer artist disturbed by a religious trauma that has psychologically affected many queer people of religious backgrounds, this writer included––former Jehovah’s Witness here. Sadly, it’s only a mere section in the film for a larger conversation that could’ve been handled in more depth.

Despite some surface-levelled areas that would have benefited from a little bit more exploration, Little Richard: I Am Everything is a complex portrait of the impact Little Richard had on the music industry and American culture. Cortés’s craftsmanship and Little Richard’s fascinating ability as a storyteller elevate the film as a mighty, affirming declaration that the culture of rock ’n’ roll would not be where it is today without him.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra