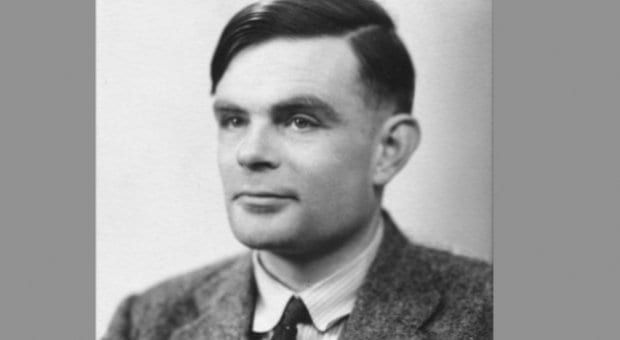

Second World War mathematician Alan Turing, who was convicted in 1952 of gross indecency after revealing a sexual relationship with a man, has been granted a long-sought, posthumous royal pardon, the BBC reports.

According to the report, the pardon, which takes effect Dec 24, was requested by Justice Minister Chris Grayling, who called Turing “an exceptional man with a brilliant mind” whose research and codebreaking work are credited with shortening the war. Turing died in 1954, his death by cyanide poisoning ruled a suicide, which is still a disputed finding.

In an interview with the BBC, Captain Jerry Roberts, who worked alongside Turing at Bletchley Park, recalled his colleague’s 1939 breakthrough in cracking the Enigma code that the Luftwaffe and the German army used and later, Turing’s success in breaking the naval Enigma.

“In 1940/41 the German U-boats were sinking our food ships and our ships bringing in armaments left right and centre, and there was nothing to stop this until Turing managed to break naval Enigma, as used by the U-boats. We then knew where the U-boats were positioned in the Atlantic and our convoys could avoid them,” Roberts notes. “If that hadn’t happened, it is entirely possible, even probable, that Britain would have been starved and would have lost the war.”

Former British prime minister Winston Churchill deemed Turing’s efforts “the single biggest contribution to Allied victory in the war against Nazi Germany.”

But Turing’s much-lauded work didn’t prevent him from losing his security privileges after his conviction. He didn’t serve prison time after agreeing to being injected with female hormones to reduce his sex drive through chemical castration.

In 2009, another former British prime minister, Gordon Brown, who called the treatment Turing endured “appalling,” issued an apology. “On behalf of the British government, and all those who live freely thanks to Alan’s work, I am very proud to say: we’re sorry, you deserved so much better,” Brown wrote in The Telegraph that year.

But the apology was not enough for thousands of people, who continued to agitate for a pardon for Turing.

For more of the interview with Roberts, see “People’s War.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra