The post was about as innocuous as they come.

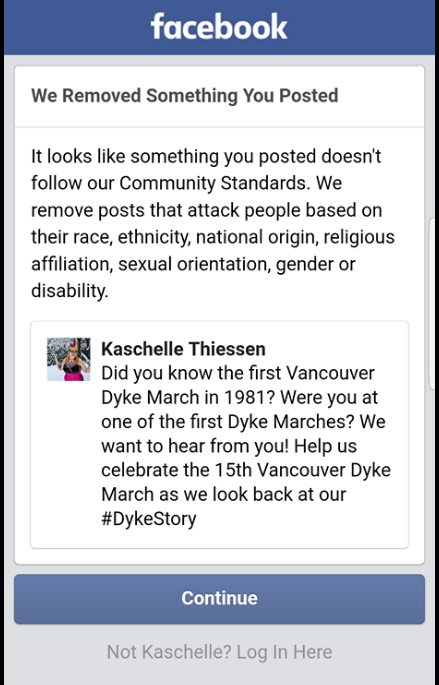

“Did you know the first Vancouver Dyke March was in 1981? Were you at one of the first Dyke Marches? We want to hear from you! Help us celebrate the 15th Vancouver Dyke March as we look back at our #DykeStory.”

But that kindly request for anecdotes from the Vancouver Dyke March’s Facebook page was not long for this world. It was quickly removed by Facebook’s content moderators because it was deemed to be an attack based on “race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, gender or disability.”

“We often see hate speech, homophobic speech, left up on Facebook,” Kaschelle Thiessen, a spokesperson for the Vancouver Dyke March and Festival Society tells Xtra. “And yet an appeal for stories about our own community was considered to be a violation of the standards of Facebook.”

It’s a story that’s played out over and over and over and over again.

Online giants like Facebook, Google and Twitter just can’t seem to grasp the nuances of what constitutes hate speech and what doesn’t. The end result is a proliferation of vile content — homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, racism, anti-Semitism and every other manner of hate — while marginalized groups have their content removed.

From the very beginning, Facebook’s real name policy, which was essential in distinguishing it from previous social networks like Friendster and MySpace, has discriminated against trans people.

Facebook removed this post from the Vancouver Dyke March page for being an attack based on “race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, gender or disability.” Credit: Vancouver Dyke March/Facebook

So why can’t Facebook in particular get a grip?

At first, it was an overreliance on algorithms, particularly the mysterious elixir that underpins News Feed, Facebook’s keystone product. But algorithms are not objective and will incorporate the biases of their creators.

“Algorithms are editorial decisions,” Cory Doctorow, the digital-rights activist, has written.

And in the last few years, Facebook has acknowledged that a human touch is required, hiring thousands of thousands of content moderators around the world.

Even when companies like Facebook and Google bring in actual humans to make decisions, those biases are still at the forefront.

After all, these are essentially factory-line workers who have to make split-second decisions — moderators literally have seconds to decide — about the type of content that’s acceptable and unacceptable.

But they are not especially equipped to handle certain types of content.

“Content reviewers tend to be hired for their language expertise, and they don’t tend to come with any predetermined subject-matter expertise,” Monika Bickert, the head of Facebook’s global policy management, said earlier this year.

Facebook doesn’t tell the public what’s allowed and what isn’t. Sure, there are general guidelines, but the company has much more sophisticated internal guidelines that they don’t release publicly.

A recent investigation by The Guardian revealed some of these guidelines. Nudity was not generally allowed, but photos of concentration and death camps during the Holocaust that included nudity were. Some types of death threats were allowed because they were seen as non-credible. Videos of abortions were okay as long as they didn’t include nudity.

Facebook says these standards are constantly evolving, but they’re also strict, so that content moderators from around the world will come to the same conclusion.

But language is complicated, evolving and contentious. When Queer Nation was reappropriating “queer” in the early 1990s, many gay, bisexual and lesbian people considered the term hate speech, even when it came out of the mouths of other gay, bisexual and lesbian people.

That’s true even today.

So you can understand, even sympathize with, the difficult position that companies like Facebook, Google and Twitter are in when it comes to policing speech.

But the problem at the core of that is not that they are too censorious. It’s that they make the wrong decision time and time and time again. While organizations like the Vancouver Dyke March are having their pages removed, hate speech continues to thrive on the platforms.

At the core of the issue is who is making the decisions and setting the policies. These technology companies come from a Silicon Valley tradition that prizes free speech and non-interference online. They are staffed largely by men, mostly straight, who are mostly white or of Asian descent. This is what happens when you have products created by a tiny, unrepresented sliver of society.

Despite the fact that the services they provide are akin to public utilities, social media giants like Facebook are accountable only to their shareholders. The Silicon Valley libertarianism is encoded into their corporate DNA and makes it impossible for them to actually examine and acknowledge the way power and marginalization operates in societies.

The Vancouver Dyke March, and other LGBT groups, will likely continue to have posts removed by faceless, unaccountable moderation teams.

Maybe Facebook and Google and Twitter will get progressively better, but they’ll never be accountable to their users or the public. The promise of the internet was that all voices would have an equal footing. But the speech of marginalized people continues to be beholden to the powers that be.

“You can’t say that you’re putting in a policy to protect marginalized communities and use it to censor marginalized communities, which is what’s happening here,” Thiessen says. “They’re using their policies against us.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra