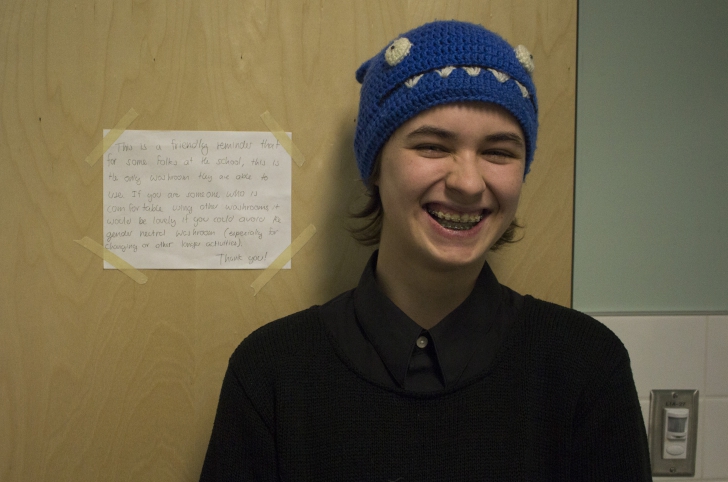

Grade 11 student AJ Wasserman says Kitsilano Secondary School is a lot more gay than it used to be.

I agree. When I went to Kits High, I didn’t identify as queer and I didn’t dare question my (presumed) heterosexuality. I was there from 2001–2006, at a time where if you were to come out as gay, you’d be the talk of the town — and not in a good way.

There was no visible LGBT community to support you. You’d be mocked endlessly, through whispers and off-hand comments. Maybe you’d find homophobic graffiti on your locker.

There were no lesbians or queer women who were out during my time at Kits. (Of our graduating class of 350, I know of five women who have since come out as lesbian or queer.)

Things have changed, Wasserman tells me now.

The school boasts a loud and visible queer community. And in the three and a half years that Wasserman’s been there, things have continued to change for the better.

“I feel like it’s gotten a lot gayer . . . there’s a lot more students out as queer,” Wasserman says, adding that Kits’ Gay-Straight Alliance club (GSA) has expanded even more since they first became a student. “And I’d say — not always, but much more than it used to be — that allies and other people in the community will stand up against the homophobia they see.”

Only three years ago, when Wasserman was in Grade 8, they couldn’t walk down the hallway where Grade 12 students had their lockers

“I couldn’t enter because I would get death threats all the way down it,” they say. One of their classes was off that hallway, and a friend would have to to accompany them to class.

Wasserman says things improved after that senior class graduated.

“It’s gotten much better. [Homophobia,] it’s not so outward but there’s still some one-on-one microaggressions,” they say, citing instances of people mocking chosen names or not acknowledging their pronouns.

Getting teachers to use gender-neutral pronouns has also been a battle, Wasserman says.

Two years ago, they had a teacher who refused to respect their pronouns. Even after their parents and school counsellor got involved, Wasserman says the teacher resisted.

Wasserman stopped attending that teacher’s class and did the school work from home.

Brandon Yan, program coordinator of Out in Schools, says he’s heard similar stories from across BC schools. Calling it “inter-generational friction,” Yan says that many older people have trouble understanding how younger folks view gender. It’s a gap in understanding that will have to close soon.

“There isn’t much accountability when it comes to educators and administrators [respecting pronouns] . . . but it is going to change fairly quickly with the BC Human Rights Code where it is literally written in law that you must respect somebody’s gender identity and expression,” he says.

Kitsilano’s Pride Team (formerly the Gay-Straight Alliance) meets every Wednesday at lunch. In late November, the students invited me to join them.

Over the years, membership has fluctuated between about five and 15 students, Sharon Fritz, an art teacher at Kits says. It also changed its name from the Gay-Straight Alliance to the Queer-Straight Alliance, but as more students came out as trans, the group eventually settled on the name Pride Team.

I ask the students about their lives at Kits High, and how safe it is to be out.

They tell me there’s a lot of support from teachers and other students. It’s fairly safe to be gay, but they still hear people using the “F-word” (as an insult) in the hallways.

Grade 11 student Tom Catyr Todd explains that a group of Grade 8 students, who used to eat lunch near their locker, would spew homophobic insults. “Part of their casual conversation would be saying horrible slurs, not just about queer people, but disabled people . . . it was horrible to hear, it was just constant,” Todd says.

In Grade 11 alone, Wasserman estimates that there are 15 students who are out, and Todd counts 10 trans students at large.

When I was in high school, I had never heard the term “transgender,” and there certainly weren’t any openly trans students.

Perhaps what’s most surprising to me is that this group of teens doesn’t hide. They held a bake sale during the school’s pride week, and only one student, known for harassing others, stopped to spew homophobic slurs. Meanwhile one teacher was eager to show his support so he bought one of everything. The Pride Team is somewhat well-received when tabling on clubs day. However, there’s an assumption by other students that if you’re in the club, you’re definitely gay. As a result, some of the younger members, still questioning their sexuality, chose not be in the club’s yearbook photo.

Back in the early 2000s, the Gay-Straight Alliance was usually absent from the clubs section of the yearbook, I tell the students. Over my five-year stint at Kits High, the GSA appeared only once in the yearbook, but the students were greyed out, in an effort to protect themselves from harassment.

I explain how there was an unspoken agreement between students: don’t ask, don’t tell — but feel free to chastise someone behind their back. By Grade 12, only one person in my grade, Kaan Yalkin, was out as gay.

Earlier that week, I had caught up with Yalkin by phone.

“For the most part it was a tolerant environment,” he says, adding that it “doesn’t mean it was perfect.”

I’ve known Yalkin since elementary school. He was outspoken and made people laugh. For example, in Grade 8 we successfully distracted a substitute teacher while he escaped through the window of our ground-floor classroom. He did it with a straight face and it still makes me laugh.

Midway through high school, I remember a friend quietly telling me that Yalkin told her he was gay. It made her sad that he seemed ashamed and wanted her to keep it a secret.

Yalkin says he always knew he was different and by Grade 9 he knew he was gay.

Yalkin is now married, lives in Seattle and works in a corporate communications job. During our senior years of high school, he was heavily involved with the cheerleading team.

“[Being] gay didn’t define me,” he says, adding that he didn’t feel comfortable joining the GSA. But, because of his sexual orientation, he carried an “overwhelming sense of vulnerability . . . to judgment, or embarrassment or inferiority.”

By Grade 12, Yalkin says he was fully out, but not in a loud way. “It was the highest point in terms of feeling accepted,” he says. However, he remained uneasy about sharing his sexual identity with male classmates.

Sometimes he was called derogatory terms, but he says it was very rare. The staff were “overwhelmingly supportive,” but he wishes LGBT staff had been more open about their own experiences.

“We may have had openly gay staff members, but it wasn’t on the table for discussion,” he says. “To have had out role models would have made it easier for the LGBT kids to be out.”

The next week, I sit down for an interview with Todd. Todd says their pronouns “always change,” and on the day of our interview prefers they/them pronouns.

Being queer at Kits is challenging, says Todd.

“It’s not impossible but it’s work . . . always like pushing and pushing and trying to get people to pay attention and respect you. And it happens if you keep working,” they say. “People will come around and pay attention to you but it’s not like people are educated or understand what you’re talking about,” they say, adding that the pushing “is tiring, it sort of wears you down”

Todd says they are frequently misgendered. At the beginning of the school year, they went to their teachers, introduced themselves and explained what pronouns they use. While most were receptive, Todd remembers one who wasn’t. Their voice wavers with emotion as they explain how that teacher barked, “What? Why would I ever use pronouns for you? Why would that ever be a problem?”

When Todd later confronted that teacher about misgendering them, they say the teacher denied the misgendering. Recalling the situation now, Todd speaks with compassion.

“In general, they seemed they were wanting to support me but they just weren’t able to do that. Maybe education reasons — I don’t know.”

Resistance to change isn’t everywhere. Todd recalls that when their English teacher has misgendered them, she’s been receptive to their corrections. Once, after she had addressed the class as “boys and girls,” Todd went up and spoke to her after class. Todd says she apologized and told them it was language she was “trying to move away from.”

I ask Todd if they know of any queer couples at the school. They say they know of one, but the pair aren’t “loud” about it, and Todd has never seen them kiss in the hallway. Earlier, I had seen two members of the Pride Team walking down the hallway holding hands, and I wonder if they’re the couple Todd is talking about.

Listening to Todd and Wasserman’s experiences, it’s easy to forget that they’re both still in high school. While I imagine they are role models for younger queer students, they both need more support from their teachers. Our conversations consistently come back to the fact that they want their teachers to better educated on LGBT topics.

Fritz has been sponsoring the Pride Team for almost 10 years, about as long as she’s been teaching at the school. She’s warm and unassuming, and students like her. She’s not queer herself, but her father came out as gay late in life.

Feeling remorse that her dad had been closeted for so long, she says, “I thought as a teacher maybe I could make a difference for students feeling safe.”

Fritz recalls that the club has seen significant shifts over the years.

“The major change is who is interested in coming and who the group is serving,” says Fritz, noting that for the most part, gay cis male students have stopped coming. She’s co-sponsored the team with other teachers, but currently she’s doing it alone. “Maybe the cis gay guys have felt that they haven’t needed the support . . . that they feel kind of safer being out in the school.”

Fritz also emphasizes the need for more LGBT-education for teachers. And while she knows it’s a sensitive and personal decision for staff to be out around the students, she would love to see it happen.

“I wish the students could see out role models in the school,” she says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra