I’m not going to beat around the bush. I despise the Catholic Church. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t care for most organized religion. But to me, Catholicism represents the worst of what religion can be: preaching virtues of humility from a golden palace, claiming to spread love while treating women as second-class citizens, denying queer people rights and actively covering up child sexual abuse. With my fiery anti-Catholicism, I probably would have hit it off with 17th-century Mexican poet and intellectual Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Born in a village southeast of Mexico City, she was baptized in early December 1648 as a “daughter of the church.” Despite being the illegitimate daughter of a Spanish captain and an illiterate Criollo woman, Inés’s mother made sure her children all learned to read as early as possible.

When she was about six or seven, Inés begged her mother to dress her like a boy so she could go to school in Mexico City, but her request wasn’t taken seriously. In a way, though, she later got her wish. She eventually was sent to Mexico City to live with her wealthy aunt and uncle and became something of a local oddity: an expansively intellectual teenaged girl was as common as a snow drift in the desert.

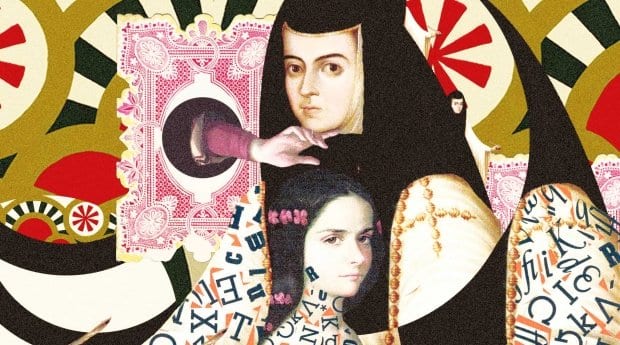

She could not attend university, as women were barred from higher education, but through her own notoriety, familial connections and beauty — in paintings she’s depicted as petite, dark eyed, impudent and fine-featured — she joined the court of “New Spain,” a fantastic educational opportunity. When she was about 16, she was a favourite lady-in-waiting of a Mexican noblewoman.

In 1669, Inés joined the Mexico City convent of San Jerónimo, a drastic change from court but essential to her intellectual survival. She wrote, “I took the veil because, though I knew I would find in religious life many things that would be repugnant to my character … it would, given my total opposition to marriage, be the least unfitting and most decent state I could choose, with regard to the assurance I wished for my salvation.” Hence, Inés became Sor (Spanish for “Sister”) Juana, and she would spend the rest of her life in the convent.

We presume a nun would lead an ascetic life, but Sor Juana lived quite comfortably in a two-storey apartment chock-full of books. During her time in the convent she wrote the bulk of her work, which included a number of passionate, erotic poems to important women in her life. In a piece that begins “Perdite, señora” — something like “My lost lady” in English — Sor Juana apologizes to a woman she loves for not writing, saying she knows her love is wrong: “And, although loving your beauty/ is a crime beyond repair,/ rather the crime be chastised/ than my fervour cease to dare.”

Along with a talent for the erotic and the transcendental, Sor Juana’s poetry had a secular and satirical bent. One riotous poem charges men with “not seeing you’re alone to blame/ for faults you plant in woman’s mind.” Her work had a feminist leaning long before any organized movement, and this got her noticed, not always in a good way.

After she wrote a criticism of a popular old sermon that was then published by an antagonistic bishop, she was criticized harshly and relentlessly by the church. She was forced to defend herself as a learned woman in “La Respuesta” (“The Response”), an intellectual masterpiece considered largely autobiographical. Eventually, she was forced to sell all her books and scientific equipment — she gave the money to the poor — and do what the patriarchal church wanted her to do all along: take her place as a woman, and nothing more.

I was raised Catholic, and I like to think my tendency toward zealous anti-Catholicism is so strong because I was able to get out. Since then, I’ve always wanted people to dream beyond the four walls of the church. I think that’s why I see such a kindred spirit in Sor Juana, who, as a polite “fuck you” to the Catholic Church, I am naming patron saint of intellects and feminists.

History Boys appears in every issue of Xtra.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra