Back in the day—the late 1990s and early 2000s, to be exact—Toronto’s Pleasure Palace was the place to be for adventurous queer women and non-cis dudes. The giant sex and play party, featuring lap dancers, DJs, a leather sling, a sauna, an outdoor pool and friendly tour guides for nervous newbies, was hosted a couple nights a year at Club Toronto, a working-class gay men’s bathhouse near Toronto’s Gay Village. The first “Pussy Palace” was launched in 1998 by the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee, a group of sex-positive feminists who wanted to create an experience akin to men’s bathhouses or cruising spots, where we could flirt, dance, hookup, watch sex and be watched, or get kinky safely and without shame. (The name was later changed from “Pussy” to “Pleasure” to recognize a diversity of bodies and to be more respectful of trans people.) By the time I was invited to join the committee in 2000, three Pleasure Palace events had been hosted without any legal problems.

Then, at the fourth bathhouse night on Sept. 15, 2000, two women undercover officers from Toronto Police Service’s 52 Division posing as patrons entered the space just after midnight and secretly surveilled the 350 guests—most of them partially dressed or nude, somes also having sex. After those first officers left, five male police officers barged in and spent 90 minutes intimidating guests while they searched the bathhouse for evidence of criminal acts. The men entered private rooms, attempted to look through personal belongings and, at one point, lingered in a room for 20 minutes questioning the two women inside. The officers explicitly prevented volunteers at the door and those doing security from warning partially dressed and nude guests of their presence.

They also aggressively questioned the head of security, volunteers and a committee member, demanding to know “who was in charge” because they couldn’t understand that the event was organized by a feminist collective with a non-hierarchical structure. When we refused to answer further questions without a lawyer, the police finally left without pressing any charges. In the space that night were survivors of sexual violence, Black, Indigenous and migrant people, people with histories in the criminal legal system and women with precarious custody of their children. Many people were deeply upset, frightened and angered by the raid. In the aftermath, we plunged into what became a five year-long legal fight with Toronto Police Service over systemic homophobia and sexism—a fight that led to a historic (and rare) ass-kicking of the police by community members, and a series of mandatory reforms.

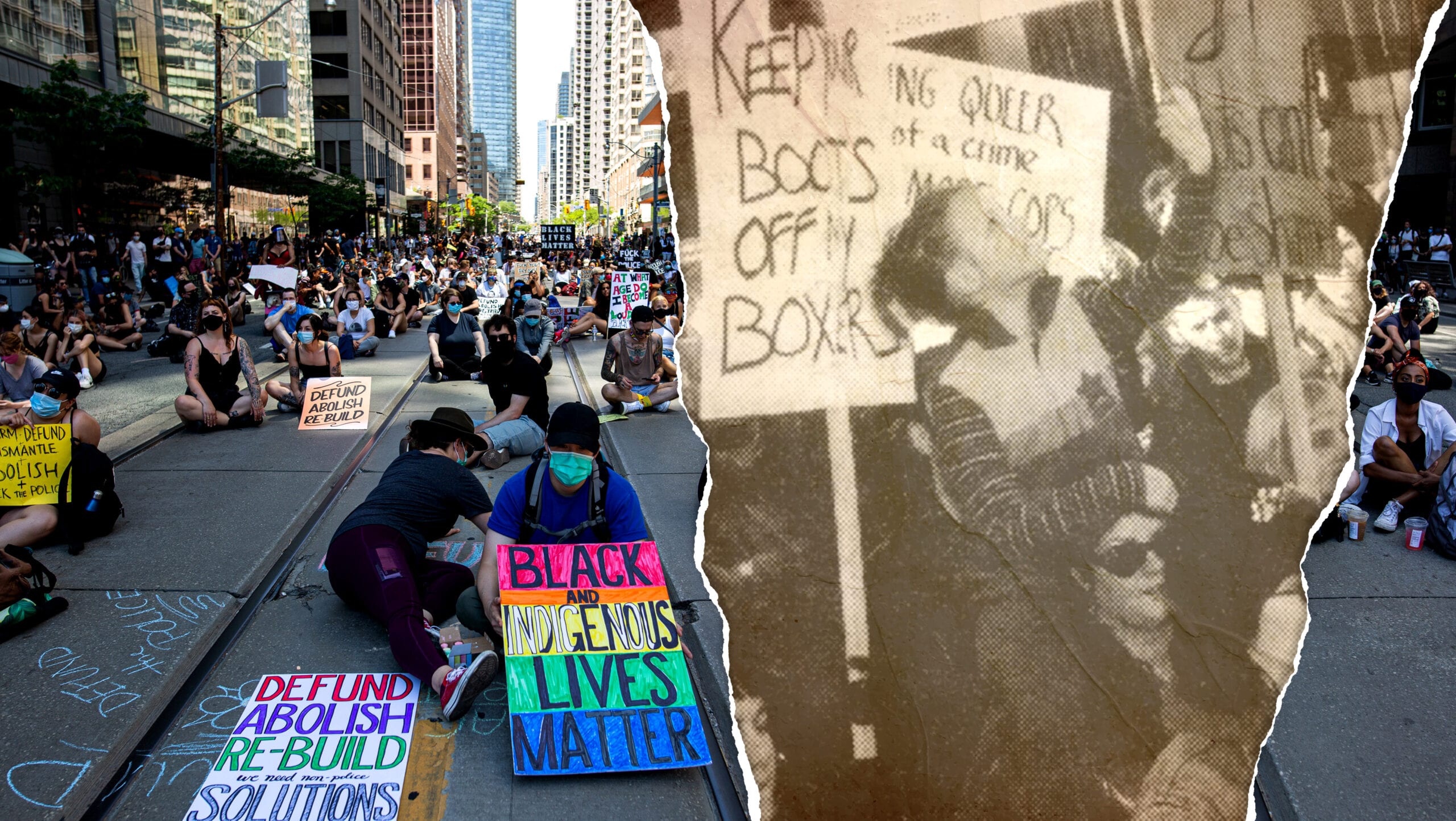

In the 20 years since the Pleasure Palace raid, much progress has been made for the rights and status of LGBTQ2 people. Canada legalized same-sex marriage in 2005. In 2017, the federal government apologized to LGBTQ2 members of the military and the civil service whose careers were destroyed during the gay purge. That same year, gender identity and expression were added to the Canadian Human Rights Act as prohibited grounds of discrimination. But as we mark the 20th anniversary of the first—and last—raid on a queer women’s bathhouse in Canadian history, queers in Toronto (and around the world) are also in the midst of a long overdue reckoning with police about systemic racism and violence, in addition to the long-standing lack of accountability toward LGBTQ2 communities.

In 2016, Black Lives Matter Toronto briefly halted the city’s Pride Parade in a sit-in against the presence of armed and uniformed officers in the parade. During that same time, the gay community was furious about how Toronto Police Service was handling the investigation into a serial killer preying upon members of the community. And as I write this, the Special Investigations Unit has yet again cleared the Toronto police of any wrong-doing, this time in the death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet, a Black and Indigenous woman who fell 24 stories after an encounter with police in her apartment. The SIU will likely do the same for the deaths of Ejaz Choudry and D’Andre Campbell, two other people of colour killed by Toronto police in recent months.

We’ve come a long way in our discussions about policing since 2000; conversations about defunding the police and abolishing prisons are being taken seriously in a new way. But looking back at the 2000 Pleasure Palace raid and its aftermath, there are still lessons to be learned both in Toronto and elsewhere. And here’s what I came to understand the hard way: The policing system can’t be fixed. If we want real safety, we need to invest in the resources our communities actually need to thrive, and support social movements to end policing entirely.

The September 2000 raid on the Pleasure Palace didn’t come out of nowhere. Public sex parties and commercial spaces like bathhouses, where sex took place, were still considered “indecent” or “common bawdy houses.” That didn’t change until 2005, when some male Québecois swingers convinced the courts that their sex parties should be legal because the women attending them were “consenting adults” who didn’t make any money—unlike brothels, where women are presumed to be unable to consent. The ruling was deeply sexist, and it reflected a degrading and patronizing attitude towards sex work. But then, so do most laws around sex.

In the months before the Pleasure Palace raid, Toronto police had been ramping up their harassment with stings at gay bars and bathhouses looking for evidence of public sex. Shortly before the September Pleasure Palace event, a member of the organizing committee received an anonymous tip that the police were planning a raid. We didn’t have confirmation and didn’t want to give in to intimidation, so we made a plan: we contacted a lawyer, drew up some “know your rights” info sheets and provided everyone entering with guidance on what to do if the cops arrived. We asked a queer-friendly reporter to spend the night at the bathhouse in case the police showed up and we needed our side of the story told. It so happened that quite a few did show up: At one point, five cop cars blocked off the street outside the bathhouse.

The day after the raid, the committee gathered in my kitchen for an eight hour meeting (on plastic chairs!) to debrief and strategize. I was the youngest and newest member and didn’t understand what had happened or how to respond. The more politically experienced members made it clear that day: we were just targeted by the police, it was illegal and we were going to fight back. I did not know what that meant, but I was in. So we paused the bathhouse events and began a whole different organizing project: Fighting the police.

Even in an age before social media, news about the raid spread through the community like wildfire, and less than a week later, 400 people packed into a public meeting we held at The 519, a community centre in the Gay Village. I was so nervous I could barely get the words out as I read the committee’s prepared statement, but the rest of the room was vibrating with outrage. At one point, city councillor Olivia Chow swooped in for ten minutes, raising about $10,000 for our newly hatched legal defence fund. Toward the end of the night, the people present—many of them gay men who’d lived through a series of violent police raids on men’s bathhouses in the early 1980s—self-organized into a spontaneous march to police headquarters, complete with handmade arm bands for safety marshals and shouts of “Out of the bars! Into the streets!”

Over the next few weeks, we watched in shock as supportive stories about our raunchy queer sex party rippled out in mainstream media outlets across the country. Even the staid Globe and Mail was incensed, characterizing police behaviour that night as harassment lacking in common sense and restraint.

A month later, the police laid six trumped-up liquor licence charges against JP Hornick and a security volunteer, both of whom had signed the special occasion permit that allowed the organizing committee to serve alcohol. In response, we held protests outside of 52 Division. (The flyer for a “panty picket” read: “Help us send a clear message to the POLICE DEPARTMENT that the community is FURIOUS that charges have been laid.”) We spoke at police board meetings, lodged a complaint against the police with the Ontario Human Rights Commission and filed a class-action suit against the Toronto Police Service for violating our constitutional rights under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. We organized fundraisers for legal fees and we held hours and hours of meetings.

It took several years, but the TL;DR version is that we crushed it. In early 2002, Ontario Court Justice Peter Hryn tossed the charges out and issued a scathing decision that said the officers had committed “visual rape,” likening the raid to an unlawful strip search. The exonerated “co-accused” were that year’s Pride parade marshals. In 2004, the Ontario Human Rights Commission decided that the cops had violated our rights and awarded the bathhouse committee $350,000 in damages, which went to legal fees and donations to community organizations. The OHRC also forced the Toronto Police Service to accept a set of demands we had drafted: hire more LGBTQ2 officers, provide sensitivity training for every single member of the service (including the chief) and develop a strip search policy for trans people—a first for any North American police force. (The policy was meant to allow trans people to choose the gender of the officers who search them.) The male officers and the police chief were all required to sign apologies. At the time, these decisions felt like victories that came straight out of community power. Maybe, together, we could force the police into a new era where they’d stop kicking LGBTQ2 people around. We were winning.

Fast forward to 2016, when the Toronto Police Service decided to apologize publicly for the 1981 men’s bathhouse raids, as well as for the 2000 Pleasure Palace raid. This time, it was on behalf of the whole police service, not just the officers involved, to express “regret” and to “acknowledge the lessons learned about the risks of treating any part of Toronto’s many communities as not fully a part of society.” And, this time, the Women’s Bathhouse Committee soundly rejected it. We had learned in the intervening years that police apologies are just for show, and we didn’t want to be part of their PR campaign. We’d been through a gruelling multi-year process with the police, dragging them kicking and screaming into reforms that we hoped would reduce their harm to our communities. And they’d had 16 years to show that their first apology meant something.

But all that sensitivity training didn’t do us any good when it came to protecting our community. Police were uninterested when Alloura Wells, a mixed-race trans woman, went missing in 2017 and was later found dead. And, when men began to vanish from the Gay Village—most of them brown—the police gaslit the LGBTQ2 community, minimizing concerns that these disappearances were linked. Later, the police failed to properly investigate and subsequently blamed the community for hampering their efforts. Toronto police couldn’t even find Tess Richey’s body after she was killed only 50 feet from where she had last been seen, in the Gay Village. But, somehow, the police did have the time, in 2016, to conduct stings on cruising areas like Marie Curtis Park. At the same time, Black people remained 20 times more likely to be shot dead by Toronto police and six times more likely to be taken down by a police dog than white people were.

Twenty years ago, I genuinely hoped that our efforts at police reform could make them more accountable and our communities safer. But it didn’t work out that way. The cops never stopped being violent and they never started protecting anyone but the rich and powerful, no matter how much public money they poured into “community relations.” Instead, they used the 2000 bathhouse raid as a public relations opportunity and cashed in. All seven officers involved in the raid sued gay city councillor Kyle Rae, in 2002, after he called them “goons” and “rogue cops,” and they won $170,000 in damages. (That money was paid by City of Toronto insurance—as in, we paid for it.) The police chief at the time, Julian Fantino, loudly complained to the press about having to institute LGBTQ2 training for officers.

But some people bought the facade and believed the police had changed. That’s in part why, in 2016, so many queers, especially white ones, could not understand why Black Lives Matter Toronto—a queer- and trans-led organization—stopped the Pride parade to insist, among other demands, that armed, uniformed police not be given a place in our celebrations. Straight media, which in 2000 had decried the presence of male police officers in the bathhouse as homophobic sexual harassment, now saw police presence in Pride (which can sometimes be about as nude as a bathhouse) as a sign of progress and tolerance. What the hell happened?

What happened was the slow (or rapid, depending on who you ask) gentrification of queer politics that began after the radical 1969 Stonewall uprising against police abuse in New York City. Back in 2000, trans women were certainly talking about police violence, and Black queer people were certainly talking about police violence. But, at a national and mainstream level, the conversation about queer politics then was about the fight for gay marriage, not gay liberation. And, in that context, fighting to improve the police—not eliminate them—made sense. Even if those “improvements” meant bigger budgets for training.

Did any of us bathhouse organizers imagine that we could demand a world without police? The human rights complaint was based on an accusation of homophobia and sexual harassment by men, not state harassment by cops, which is why only the male cops were forced to apologize. The fact that the women undercover cops who surveilled us had the same power to arrest, sexually harass and kill was minimized. Public opinion saw it the same way. One headline about the raid read: “Our wanking boys in blue.”

To be honest, though, whether we could have imagined it or not, the right to live police-free was unwinnable at the time. And the stakes were high. Our friends had charges against them to fight. When trans women of colour, like Stonewall-era activist Sylvia Rivera, said, “We always felt that the police were the real enemy,” who listened? Not the courts. They wouldn’t have listened to us either. So we did our best to demand reforms that we thought would make the policing slightly better and our communities slightly safer.

And here’s what I learned over the 20 years in which I have been fighting criminalization as an activist for sex workers’ rights and racial justice: The police don’t change because the police can’t change. They may say that their job is to maintain public safety, but the real role of policing is to maintain inequality. They enforce unjust laws that punish people who are surviving poverty through sex work, petty theft, drugs and homelessness. The police are more than willing to abuse and kill Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of colour. Police do nothing to prevent sexual violence and are prone to committing it themselves. (Toronto police were investigated 82 times for sexual assault between 2013 and 2019. Charges were laid in only five cases.) There is no fair version of policing because unfairness is their literal job.

The Pleasure Palace victory deserves to be remembered. And that victory was also a product of its time. It was an era when some of us believed that a more rainbow-hued police force could make a difference. Now I know that our best shot at ending racist police violence is to support Black- and Indigenous-led movements to invest in the resources that our communities actually need to thrive, like healthcare and jobs, while drastically reducing police budgets and eventually abolishing the police altogether.

This is one reason I’m so thrilled that organizations like Black Lives Matter, Free Lands Free People and so many more have made it possible for us all to imagine a world without the violence of policing and to show us a pathway there. Through these visionary movements, I’ve been able to see that we don’t need cops and we never did. The Pleasure Palace had its own volunteer safety team that dealt with issues like consent and fire codes. We promoted a culture of consent, and the bathhouse events were by and for the community. It was an imperfect system, but it was certainly better than a gang of armed goons.

The Pleasure Palace was a sex-and-play party, but it was also deeply political. It was an attempt by radical queer women to create a public sexual space as a site of resistance, to politicize ourselves through sexual community, to launch a thousand orgasms and a thousand activists. And it did just that. Many activists got their first anti-oppression education through the bathhouse and went on to launch their own projects, including the BIPOC-led “Sugar Shack” sex parties. Club Toronto is now the “upscale” Oasis Aqualounge, and the Toronto Women’s Bathhouse Committee eventually folded. Gone are the sticky floors and tubs of Crisco—and, with them, a site of queer political power, where we saw what we could accomplish when we came together (all puns intended). The bathhouse was a microcosm of queer community—imperfect, gutsy and visionary. And that’s exactly the energy we need right now, in the fight to divest from the police and invest in the people.

The Arquives, the LGBTQ2 archives based in Toronto, hosts an online panel honouring the legacy of the Pussy/Pleasure Palace raid on Sept. 26 at 7 p.m. EST. Panelists include JP Hornick, Deb Singh, Carol Thames, Nik Red and Chanelle Gallant, with moderator Anna Camilleri. The event is free; go here to register.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra