In 1975 Janko Naglic opened Jo-Jo's on the second floor of 418 Church St, just south of Carlton. Les Cavaliers, a restaurant, operated on the first floor. Credit: Xtra file photo

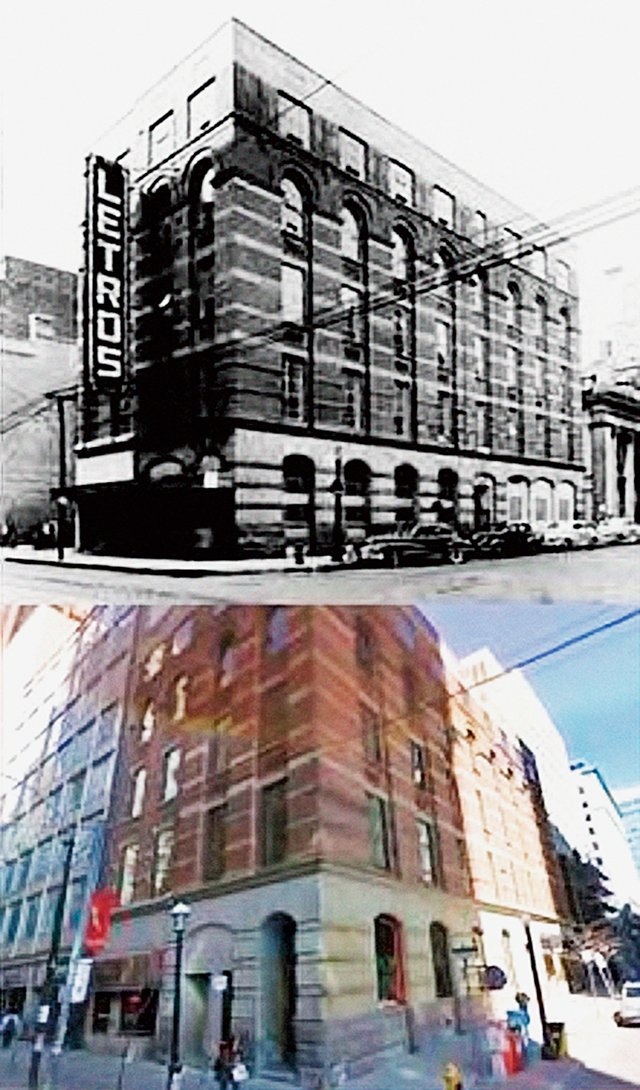

50 King St E past and present: site of the Letros Tavern, an early gay hangout. Credit: Xtra file photo

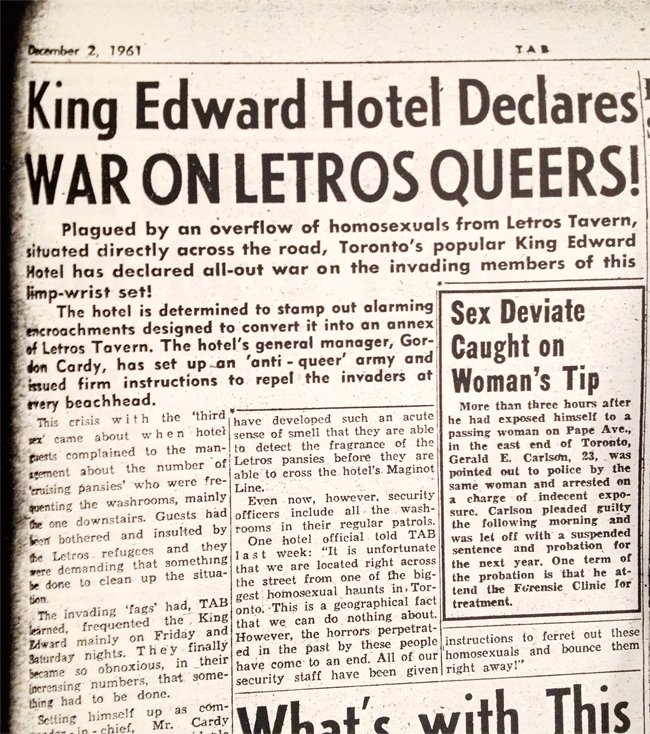

Clipping Credit: Xtra file photo

The Black Eagle moved into the Village in 1994 and now occupies the space that was formerly Tanks and the Bulldog. Credit: Xtra file photo

Claude Charles and Kristyn Wong-Tam attend a meeting at The 519 in March 1994. Credit: Danny Ogilvile

Cawthra Park buzzes with activity in July 1993. Credit: Xtra file photo

AIDS memorial Credit: Xtra file photo

A temporary AIDS memorial in Cawthra Park was replaced by the permanent AIDS Memorial in 1993. Credit: Xtra file photo

The St Charles Tavern was a popular men's bar in the 1960s and '70s. The historic clock tower remains above Yonge Street today. Credit: Xtra file photo

As Toronto prepares to host WorldPride in 2014, Xtra takes a closer look at what makes a gay village. In the first of a five-part series, Daniela Costa digs into the history of the Church-Wellesley Village.

When WorldPride hits Toronto in 2014, the Church-Wellesley Village will become, even if briefly, the focus of many queer eyes.

It’s a well-deserved prize for a community that has long strived to make Toronto a gay-friendly city.

“There will be a resurgence of pride in the Village when people come together for WorldPride,” says Ward 27 Councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam.

But should it really take a 10-day international event to drum up interest in a local social space that, considering our city’s broad history, is still a relatively new phenomenon?

That Toronto has a gay village is an accomplishment in itself. Only decades ago, the city’s gay community had no place to call its own. Queer life in Toronto used to be incredibly fragmented. No fixed meeting grounds meant that creating queer institutions went hand in hand with community building.

Prior to the mid-1970s, very few would have predicted that the Church and Wellesley neighbourhood would become the heart of Toronto’s gay community. In fact, a look back at early queer history in Toronto reveals that gay folk have never restricted themselves to one area of the city. Recall that the federal government decriminalized homosexuality only in 1969. Prior to this, gay people had to be quite stealthy. For example, in the early 20th century the lack of gay bars and bathhouses meant many men took to laneways, public lavatories and parks to satisfy their desires.

Steven Maynard teaches the history of sexuality at Queen’s University. He cites the spread of consumer capitalism as a key moment in Toronto’s queer history. Increased salaries meant some could establish independent lives, thus stimulating gay activity within the city.

“Crucially, it also had to do with the courageousness of queer people to declare their dissident desires by parading in public in non-conventional gendered ways,” Maynard says. “Ways that announced their sexual difference to everyone.”

Queer women had it harder because of exclusionary attitudes toward females in general. Public space was more difficult and dangerous to come by. The fact that most women did — and do — earn lesser salaries than men held them back as well.

“Still, there were many brave lesbians, especially butch women, who defied the norms and claimed their space on public streets,” Maynard says.

In the 1950s, for instance, pickup trucks and motorcycles were a common sight outside the White Chef, a diner on Yonge Street just north of Gerrard. The Continental Bar was another lesbian favourite in the 1950s and early ’60s.

Even back then, gay gals and guys sometimes mixed, at dances at the Maison de Lys (later the Music Room), for instance. In 1962, the venue opened at 575 Yonge St, just north of Wellesley. It’s considered one of the first clubs where gay men and women could go for same-sex dancing in Toronto.

Places like the Music Room cemented the fact that, for men and women alike, Yonge Street was the gay destination in the 1960s and ’70s.

“That was the place gay bars could flourish in a slightly seedy section of town without offending sensibilities,” says Shawn Micallef, a senior editor at Spacing, an urban landscape magazine.

What some call seedy, others call dreamy. Writer James Dubro, 66, moved to Toronto from Boston in 1970. He fondly remembers the Yonge strip. “It was mostly a fantasy land,” he says. “It was sex, sex, sex in the 1970s.”

Dubro visited his first Toronto gay bar the night he arrived in town. “It was Charlie’s,” he recalls.

He’s talking about the St Charles Tavern, a joint that, along with the Parkside and Letros, ruled the gay male scene in the 1960s and ’70s. The St Charles and the Parkside made the area just south of Yonge and Wellesley a gay hotspot. Located further south, Letros brought men to Yonge and King.

The Parkside was also a hangout for cops. The bar’s owners allowed police to set up a spy post meant to entrap men having sex with other men. The St Charles wasn’t the safest of places for gay men, either. On Halloween, a mob would gather outside and pelt patrons, particularly drag queens, with eggs and rotten fruit.

Such incidents made it clear that Toronto needed legitimate queer establishments, and gay entrepreneurs soon caught on.

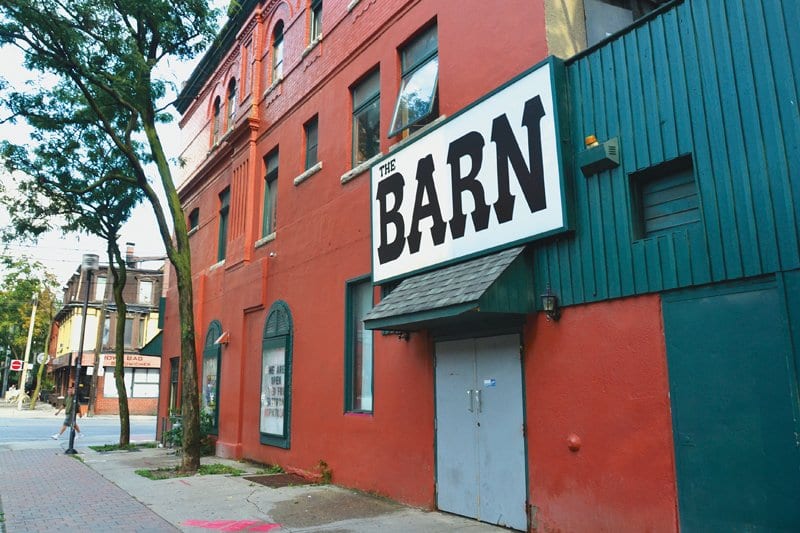

One of these entrepreneurs was Janko Naglic. In 1975, Naglic opened Jo-Jo’s on the second floor of 418 Church St, just south of Carlton. Les Cavaliers, a restaurant, operated on the first floor. By the 1980s, it became The Barn/Stables.

The Barn closed in 2004 after Naglic was found dead in his home. The nightclub reopened in 2007 before saying a final goodbye last summer.

Other standouts during The Barn’s early days included Buddies bar and Crispins restaurant, both on the northwest corner of Gerrard and Church. Today, the Hassle Free Clinic is one of the corner’s occupants.

“In the ’70s, the area around Gerrard and Church was gay central,” Dubro says.

By the end of the 1980s, however, people were taking their gay business up Church Street in strength. “We used to call it the ghetto,” Dubro says. “The ‘Village’ came in sometime in the late ’80s as a concept.”

Throughout the 1980s, gay establishments began popping up in the Church and Wellesley area. One of the most notable is Woody’s, which opened in 1989.

“Woody’s has been vitally important in terms of making it the centre and attracting other businesses to be there as well,” says Robert Windrum, president of the board of directors at the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives (CLGA).

Located at 467 Church St, Woody’s was one of Toronto’s most popular gay bars by the early 1990s. Its success solidified for many the notion that the Church and Wellesley neighbourhood could be a prime location for a gay entertainment district.

Ever the savvy businessman, Naglic had by then already dipped his toes in the Village. In the 1980s, he opened a restaurant and lesbian bar at 457 Church St. Over the years, the venue was known as Together, Tanks and the Bulldog. The Black Eagle, which has been in the Village since 1994, moved into the space in 1997 and has been there ever since.

Invited by Naglic, Dubro once dined at Together. He says female patrons gave him a less than warm welcome. “They weren’t too happy when I sat down and chatted with them,” says Dubro, chuckling. “Things were a little more segregated then.”

Some Village veterans believe gender relations in the neighbourhood have improved considerably.

“We have a much better amalgamation of the girls and guys today,” says Michelle DuBarry, 81, a legendary Toronto drag queen.

Still, women in the Village get the short end of the stick.

“We have very little here appealing to gay women,” says David Wootton, manager of the Church Wellesley Village BIA.

Wootton says places like the recently opened Davids Tea are a good fit for the Village because they appeal to both men and women.

For those less than enthused with chains, fortunately, the Village isn’t all business. Some of the groundwork for these businesses actually comes courtesy of social service agencies, such as the 519 Church Street Community Centre.

“The 519 is one of the anchor organizations in the Village,” Windrum says.

The 519 served as the early meeting ground for several gay and lesbian groups, a result of the city’s decision to convert the property into a community centre in 1975. Today, The 519 continues to welcome these groups as well as the broader queer community, providing social services and entertainment opportunities.

Next to the community centre is Cawthra Park, home to the AIDS Memorial. Managed by The 519, the memorial is the site of the annual AIDS Candlelight Vigil.

In the midst of the epidemic, Cawthra Park became a place of gathering. Volunteers set up temporary versions of the AIDS Memorial in the park for Pride Day, beginning in 1988. The permanent memorial opened in 1993. “Once the AIDS Memorial was put there, it became a focal point for our collective loss,” Windrum says.

The park also served as a vital public square for socializing. These days, Windrum doesn’t believe it’s being used in the same way. But he’s hopeful. “I think it could be overhauled to be what it once was.”

This stretch of land has gone through enough transformations to suggest this could very well be the case. After all, Cawthra Park is a man-made space. Before being demolished, a Loblaws and its parking lot stood where the park now does.

Today, Loblaws is back in the Village, comprising part of the former Maple Leaf Gardens at Carlton and Church. The reemergence of Loblaws has meant that many local shop owners are struggling to keep their doors open.

“That has hurt the Village more than anything else, yet gay people shop there,” Dubro says.

But big business’s domination of the little guy in the Village goes well beyond Loblaws. And not everyone’s crying foul. DuBarry, a Village resident, says she welcomes big business in the neighbourhood. “Presumably, there’d be gay people working in that business,” she says.

Indeed, we can’t forget that money sustains the Village. “There was never a time when things weren’t commercial,” Dubro says.

He would know; he had a front-row seat to the early development of the Village. In 1983, he lived in an apartment at Church and Gloucester. “There wasn’t really a gay village then,” he says.

But it would start to take shape soon after, as major commercial development hit the neighbourhood’s core.

For many, Church and Wellesley’s four corners immediately come to mind when picturing the Village. Until the early 1980s, however, the stretch was mostly a parking lot. This changed when in 1984 the Churwell Centre (Village Centre) opened. Running along the west side of Church from Wellesley to Maitland, the centre has had significant commercial influence in the area through its various shops and restaurants.

When a Second Cup opened that same year, it became the centre’s most famous occupant. Or, to be precise, “The Steps” did. Occupied virtually 24/7, the stairway outside the coffee shop was synonymous with the Village and provided a meeting spot for young and old alike. Unlike dance clubs, one didn’t have to be of age to gain access to The Steps, and one didn’t have to pay cover.

“It had been such an institution,” Dubro says. “It was a mixture of everything and quite a tradition.”

New owners removed The Steps in 2001. The Second Cup closed a year later.

These days, intergenerational mingling in the Village is dwindling. DuBarry says today’s youth “have their own thing going on.”

Not even the opening of a new Second Cup in 2011 could fix that reality. The café, along with Acme Burger, occupies the location previously held by Zelda’s, a staple restaurant in the neighbourhood since opening in 1997. Zelda’s closed in 2009 before reopening as Zelda’s Living Well at 692 Yonge St in 2010. On June 16, 2012, a fire at Zelda’s caused extensive damage, leading the restaurant to close its doors for good.

Increased rent is largely why Zelda’s left the Village in the first place. It’s a reality countless local business owners face. “Some places have been priced off the strip,” Micallef says.

Demand for retail space has driven up the price of commercial lease rates. According to Wootton, most business owners pay $4,000-plus in monthly rent to be in the Village core. Property taxes on the strip are nothing to laugh at either.

“Our property taxes are so high on Church Street,” says Wootton, who claims business owners pay $6,500 to $8,500 in taxes for second-level properties in the Village. Such numbers are discouraging for new entrepreneurs, yet some are still willing to take the risk.

Andrew Archer is the co-founder of Church on Church, which opened last summer. “To operate in the Village is a bit expensive,” he says. “However, there is much opportunity to be had.”

Archer says his desire to see the creation of something new for the area is a large part of why he took on the project. “Being a resident in the Village and an entrepreneur myself, it saddens me to see local business shut down,” he says.

For now, that won’t be the case for Church on Church. Archer says business is great and credits his success so far on implementing a solid business plan.

Micallef thinks businesses like Archer’s will continue to embrace the Village’s queer theme because that’s what consumers want. “Church Street will remain the gay identity strip,” he says.

Yet some think the strip would become more popular if it broadened its customer base. Wootton feels the Village should not depend solely on the business of queer folk. “We’re now becoming an urban district that appeals to a wide variety of people, not just LGBT people,” he says. “And that’s a good thing.”

But other urban districts also appeal to the queer community. By the late 1980s, Toronto’s queer patrons and residents had begun spreading out of the Village. That reality continues today. “Queer West” and areas in the east end, such as Leslieville, have become the stomping grounds of a significant portion of the city’s gay community.

Richard Florida sees this growing acceptance of queer folk as a sign of a changing city. Florida is an urban-studies theorist and the director of the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto. Together with his U of T colleague Kevin Stolarick and Gary J Gates, Florida came up with the “3Ts of economic development” — technology, talent and tolerance.

“Tolerance and openness to the gay community has a positive effect on everything from high-tech businesses to incomes and housing prices,” says Florida, who claims that as the city grows, it’s only natural that the Village change as well.

Toronto is certainly better for its progressive turn. Indeed, Florida’s research shows that “openness to the gay community is part of the equation of a great prosperous city.”

The queer community has tuned in to the city’s changing attitudes. Today, queer people live and work all over Toronto. Many even believe there can be several gay villages, just as there is more than one Little Italy and more than one Chinatown. “If gay was an ethnicity, Church Street would just be another one of Toronto’s great ethnic strips,” Micallef says.

Carl Hiehn is happy to share clientele with the Village. He’s the manager of The Beaver, a bar on Queen West. “There is no ‘battle’ between Church Street and Queer West,” he says. “There are differences, certainly, but no such battle.”

Hiehn says The Beaver receives an equal mix of queer and heterosexual customers. “Our customers are very diverse, and our parties and services reflect that.”

DuBarry says she’s in negotiations to take her drag act to The Beaver. She already performs regularly at Crews & Tangos. “It’s not just the Village anymore,” she says. She believes queer events in the west and east ends don’t interfere with the success of Church Street.

Archer agrees. “I see it more as a changing environment,” he says of the added competition. “Businesses in the Village need to adapt to the new landscape to stay relevant.”

They can take the example of Peter Bochove, 64, who since 1998 has successfully run Spa Excess, a bathhouse located on Carlton near Jarvis. “My business is booming,” he says. “I don’t have a reason to complain.”

Bochove’s business, however, is not part of the Church Wellesley Village BIA. Don’t tell him Spa Excess and the Village are mutually exclusive, though: “We’re very much a part of the community.”

Since he runs a bathhouse, Bochove says, it’s best his establishment be a bit out of the way because clients appreciate discretion. The fact that the business is only a short distance away from the Village’s core puts Bochove’s bathhouse above many others. He claims he gets email inquiries from out-of-towners asking how close to the Village his bathhouse is.

“The rest of the world knows there’s a Village here,” he says.

Experience has taught Bochove that a sizeable business like his operates best in the Village area because that’s where there’s a large enough gay population to support it.

Of course, there wasn’t always a heavy gay population in the area to support queer business endeavours. Gay business likely wouldn’t have moseyed over from Yonge to Church if not for an already existing queer residential presence in the area.

The Yonge Street strip has long since had too much going on to be the foundation for any community. By contrast, traditional patterns of urban planning made the nearby Church and Wellesley area a logical gay enclave. The Village can boast a particularly favourable location: it’s close to the hustle and bustle of the downtown yet not swallowed by it. It’s also relatively easy to get to; proximity to the subway gives the Church and Wellesley area an edge over many spots in the city.

It’s likely no coincidence that the surge of high-rise construction in the neighbourhood coincided with the building of the Yonge subway line, which opened in 1954. The original stretch of the Yonge line included Wellesley Station.

The City Park apartments also opened in 1954. In those years there were very few high-rise residences in downtown Toronto. Bounded by Wood, Yonge, Alexander and Church streets, City Park became a housing cooperative in the 1980s.

By the mid-1960s, several other towers had gone up in the neighbourhood. For instance, the Village Green — made up of three buildings at 55 Maitland St and 40 and 50 Alexander St — had its unveiling in 1966. The constant shuffling in and out of residents took the joy out of apartment living for nosy neighbours.

“Apartments are where a gay person can live rather anonymously,” Micallef says.

Now the Village has quite a mixed bag of residents. Some are queer, some aren’t. Students, retirees, families — the list goes on. None will be caught off guard when new residential complexes expected for the area materialize.

It’s all part of the reality of gentrification — a reality that’s seeing the face, and faces, of the Village changing. “It has become much more middle and upper-middle class,” Dubro says.

It would have to be. High rent is keeping some would-be Village residents at bay while also straining the purse strings of many current residents.

“The thing I worry about most is that my staff won’t be able to afford living in the Village 10 years down,” Bochove says.

Gentrification doesn’t have everyone up in arms. Wootton says that the Village is in a state of transition and that gentrification is an important aspect of this transition. “Gentrification can be a good thing if it’s about communication and support of everybody’s needs,” he says.

But communication isn’t necessarily happening. Wootton claims most property owners don’t participate in BIA discussions and, should this continue, beautification efforts in the area will fall flat. “The only way it’s going to work is if they work with us,” he says.

He wants that cooperation to come soon. With WorldPride in mind, the BIA is putting much of its focus into neighbourhood beautification.

“I think we’ll be getting more injection from the city in the next coming years,” says Wootton, who’s counting on Councillor Wong-Tam to push for funds.

Big spending from the city is certainly never the norm in the Village. Micallef claims that for most of its history there was no official support from the city and that, even today, most support comes indirectly in the form of the BIA.

“We worry about it a lot, but it’s really chugged along on its own,” he says.

He must think it’s chugged along quite nicely because, despite having visited several of North America’s gay villages, he still considers Toronto’s one of the best.

Five years ago, for example, Micallef checked out Chicago’s Boystown and was less than impressed. “It was a lot more sparse,” he says. “It didn’t have that same kind of continued street presence.”

Wong-Tam plans to make the most of that street presence, and she wants the city to help. Take the mural project she and the BIA are dreaming up, which requires sponsorship from Village property owners and city agencies (see page 24). It aims to draw not only more Torontonians to the Village, but visitors from all over the world as well.

The idea is that the murals will cover the sides of several buildings along Church Street with images that pay homage to Toronto’s sexual-liberation and gay-rights movements. “It’s important that we start thinking about who was here before us,” Wong-Tam says.

With all this talk of beautification, Wootton wants it to be clear that the BIA’s goal isn’t to sanitize the area by desexualizing it. According to him, the BIA very much wants the Village to maintain its sexy image.

“We celebrate sexuality and sexiness,” he says.

Bochove doesn’t see it quite that way. “I see this move and it makes me nervous,” he says. An activist since the bathhouse raids of Feb 5, 1981, Bochove has fought too hard for the right to freely express one’s sexuality to see it subverted in any way today.

“This family-friendly bullshit on Church Street is too much,” he says. “I want to see a street for queers.”

Precedent indicates that will remain the case. “Everyone said the Village would fall apart and it hasn’t,” Dubro says. “I don’t think it will.”

It shouldn’t. Those who haven’t yet discovered the Church-Wellesley Village deserve the opportunity to judge for themselves in the years to come. For gay youth yet to come to the Village, the experience could be invaluable.

“There must be something still pretty awesome about standing on that corner for the first time and seeing a place that isn’t just accepting of you, but is triumphantly celebrating who you are,” says Micallef.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra