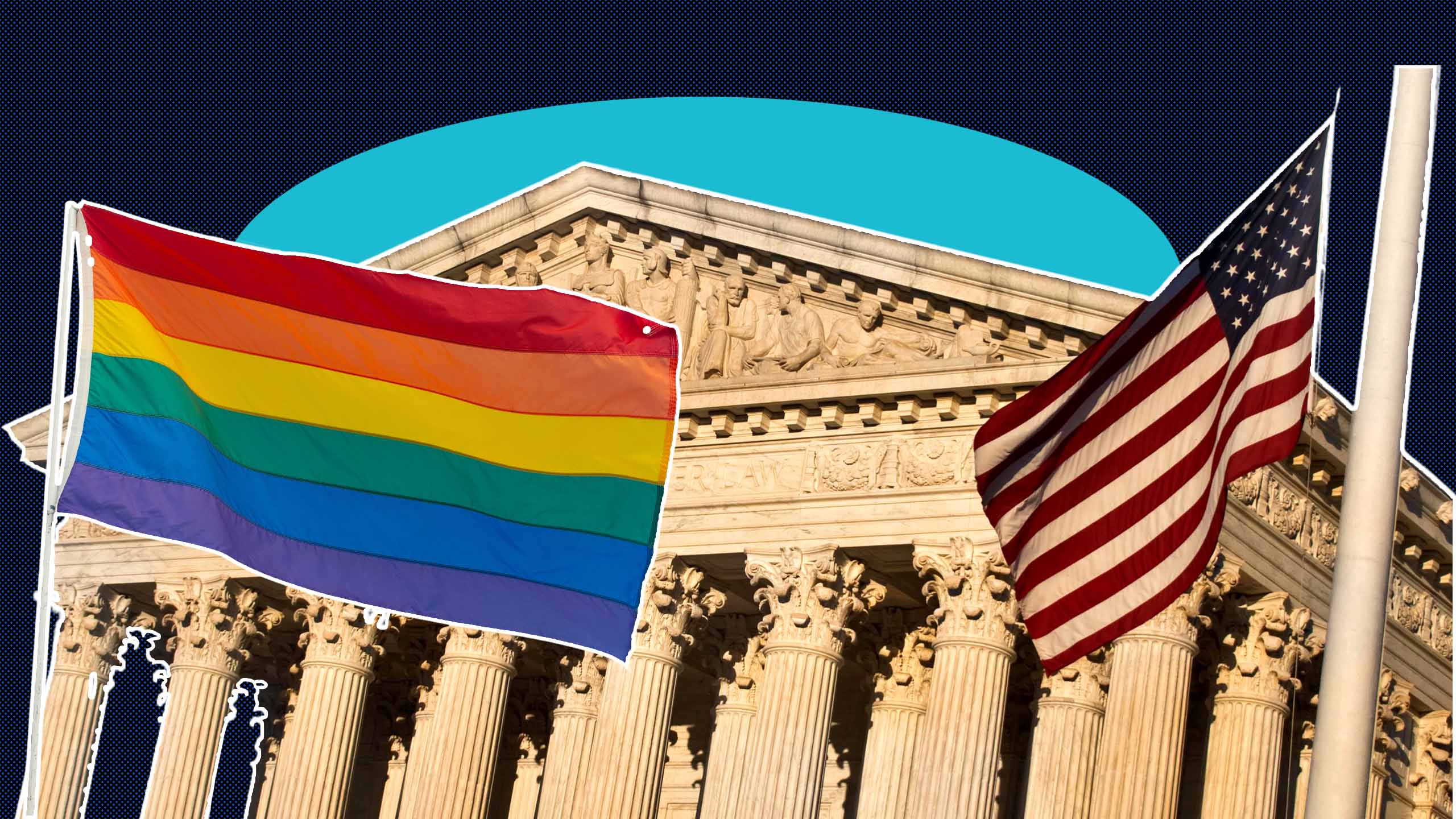

It comes as no surprise that the United States Supreme Court is poised to overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 decision that provided a constitutional right to abortion. Successive conservative presidents have stacked the court for just this purpose, and the court has chipped away at it for decades. But it is still shocking. If Justice Samuel Alito’s leaked opinion becomes law, it will mean that almost overnight, millions of women and trans people will no longer be able to access safe, legal abortions. As if that is not horrendous enough, the damage will not stop there. The entire house of cards that has been built on Roe may also soon come tumbling down. And that house contains many of the laws and rights concerning sexual orientation and gender identity.

Few legal decisions have been subject to as much critique from their inception as Roe. It single-handedly mobilized the anti-choice movement, which, for decades, has rallied against the decision with laser focus. Even many who supported the right to choose criticized the basis on which the right was granted: privacy. In Roe, the court held that the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution included a “right to privacy” that protects a pregnant person’s right to choose whether to have an abortion. That’s the amendment that guarantees that no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.”

True, privacy is not mentioned in the 14th Amendment; it is not mentioned in the Constitution at all. Yet Roe didn’t invent the right to privacy. The Supreme Court first recognized it in earlier cases dealing with access to birth control by married couples (in 1965), and then birth-control access for unmarried people (in 1972). This privacy right was said to exist in the nebulous space of the “penumbras” of the rights guaranteed by the constitution—rights that are implied, if not stated. It was this right to privacy that was extended in Roe to include the right to choose an abortion.

“Equality might have been a stronger basis on which to build the house.”

But what privacy gave with one hand, it took away with the other. A right to privacy was predicated on the state staying out of the intimate lives of individuals, which limits other things governments can do. Within a few years, in 1980, the Supreme Court confirmed that there was no constitutional right to have abortion funded. Staying out of people’s lives meant exactly that: staying out. The state was under no obligation to provide the financial means to access abortion. Some feminists would argue that framing the state as a threat to freedom, a possible infringer on their privacy, can paralyze the state from taking the kinds of actions required to promote equality. And it’s true that equality might have been a stronger basis on which to build the house (more on that later). But it wasn’t the path taken by the U.S. Supreme Court when this journey began in 1965.

Over the decades, this right to privacy became the basis for other landmark decisions, including some of those dearest to LGBTQ2S+ Americans. In 2003, in Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court (finally) struck down sodomy laws as unconstitutional, on the basis that they violated the right to privacy. At that time, 14 states still had laws criminalizing sodomy, defined variously as consensual oral and/or anal sex between any two or more adults, with four states specifically prohibiting consensual same-sex sexual acts. According to the Supreme Court: “The petitioners [Lawrence and Garner] are entitled to respect for their private lives. The State cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime.”

The same-sex marriage decision came more than a decade later: 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges. In it, the Supreme Court held that the fundamental right to marry is constitutionally guaranteed to same-sex couples by the Due Process Clause—the one that’s been the basis of privacy rulings—and also the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, prohibiting states from denying “any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” It was a right, again, based on a fundamental right to make decisions about one’s private life: “the right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy.”

“Any right that is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution can only be recognized if it is ‘deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition.’”

Fast forward to the leaked draft that may very well overrule Roe. This wouldn’t be the first time the U.S. Supreme Court has overruled past cases; some of the most important civil-rights decisions have done just that. Perhaps most notably, in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, an 1896 decision that had upheld racial segregation. Lawrence was an overturn of a past decision, too, overturning Bowers v. Hardwick, a 1986 decision that reasoned that the Constitution did not confer “a fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy.” (The man at the heart of the case, Michael Hardwick, had been observed by a Georgia police officer while engaged in consensual gay sex with another adult in the bedroom of his home.) Yet the forthcoming Roe ruling will be part of a new trend of court rulings taking away rather than granting rights, a trend that includes decisions that have chipped away at the 1965 Voting Rights Act, making it more difficult for Black Americans to vote.

The leaked Roe opinion tries to insist that it is only about abortion, distinguishing it from other protected matters such as “intimate sexual relations, contraception and marriage.” Abortion is not mentioned in the Constitution, the draft says. But then again, neither is the right to privacy on which rulings on intimate sexual relations, contraception and marriage are based. According to the Alito draft, any right that is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution can only be recognized if it is “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition.” Abortion isn’t. But neither are many other rights that may affect people, particularly LGBTQ2S+ people, as deeply and intensely as abortion rights affect people who can get pregnant.

“The folks who have packed the court with conservative judges are not finished.”

While governmental concern about sodomy might seem passé these days—would anyone dare prohibit gay sex or other kinds of consensual sex?—prohibitions against it might have a new hold. Is the right to have sex with your gay, lesbian, trans or nonbinary partner deeply rooted in America’s history and tradition? Probably not so much, according to the same people who are bringing you the overruling of Roe. Is same-sex marriage, which has only been available in the United States since 2003, when a Massachusetts ruled in favour of same-sex marriage, “deeply rooted” in history and tradition? Perhaps not, considering the people who are backing the outcome of this forthcoming decision are the same politicians who are passing “Don’t Say Gay” laws and criminalizing gender-affirming treatment for trans youth. Legal progress for LGBTQ2S+ Americans is relatively new—and still under serious attack. Opponents can now claim these rights are not deeply rooted in American history and tradition, and so should be up for reconsideration. And make no mistake. The folks who have packed the court with conservative judges are not finished.

Privacy was always a weak basis on which to build substantive rights; the right to be left alone only goes so far. And “penumbras” haven’t proven to withstand the test of time of constitutional foundations. Going back to the 1965 ruling on access to birth control, would a basis in equality, rather than privacy, have fared better over time?

In Canada—which, of course, has its own Constitution, its own 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms and a Supreme Court with its own distinctive approach to law—most LGBTQ2S+ rights have been built on equality: “Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.” The Canadian Charter lists examples of categories that are explicitly protected from discrimination (race, ethnic origin, sex, age and others), but in rulings over the years, Canada’s Supreme Court has also considered the Charter to include categories like sexual orientation, even if they are not explicitly mentioned.

In contrast, in the United States, the approach to discrimination based on sex has left a lot to be desired. Sex isn’t mentioned in the Constitution, just “equal protection of the laws.” The Equal Rights Amendment, which would have included discrimination on the basis of sex, was never passed. So, sex discrimination doesn’t have the highest level of protection. And in terms of sexual orientation, a few of the same-sex marriage cases have suggested that it has something to do with equal protection—but how or how much is not very clear. And what rights might be protected? This Supreme Court seems all too ready to take anything away that wasn’t in the minds of the dudes who wrote the Constitution.

Is there any hope on the horizon? (Spoiler: Not really.)

Okay, here is a little hope. Recent trans rights victories, rare as they may be, have usually been based not on the Constitution, but on the right to non-discrimination in the Civil Rights Act and on a rejection of the rights to privacy of parties challenging trans accommodation policies in schools; yes, in these cases, privacy arguments were being used not to protect trans students, but to attack them, and the trans advocates won because the judges didn’t consider privacy rights of those who didn’t want to share the spaces with trans students to be paramount. Striking down Roe would likely not be a direct threat to these cases because they have their own unique reasoning. But these are the same folks, the same judges, with the same underlying ideologies. What they can do to Roe today they can do to other rights tomorrow.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra