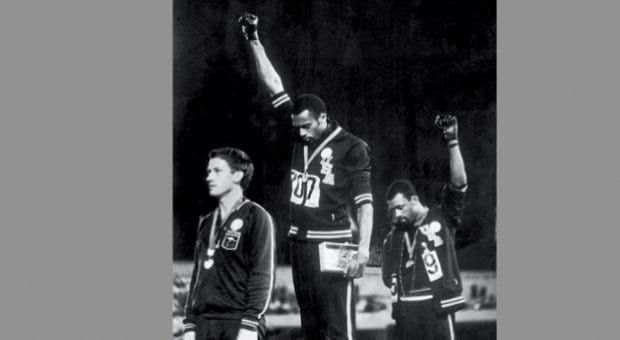

Shoeless and wearing black socks, athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos mounted the podium at the 1968 Olympics, accepted their 200-metre-sprint gold and bronze medals, then raised their black-gloved fists and bowed their heads as the American anthem played.

Their now iconographic protest gesture initially went unremarked in the midst of a packed stadium, notes a 2008 Smithsonian retrospective marking the 40th anniversary of the athletes’ silent but powerful stand for “strength and unity” against poverty, racism and lynching.

At the time, the US was in ferment from the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, the volatility of anti-war demonstrations, and the beating of protesters by Chicago police at the Democratic National Convention.

Back at the Mexican Olympiad, the third athlete on the podium, Australian Peter Norman, wore a badge in solidarity as he claimed the silver medal.

Prior to the ’68 Games, there had been talk of a boycott by African-American athletes to highlight the systemic inequalities rending US society.

For “politicizing” the Games, Smith and Carlos were suspended and banished and faced heavy criticism and even death threats.

Still, both men maintain they have no regrets about that October day.

“I went up there as a dignified black man and said: ‘What’s going on is wrong,’” sportswriter David Davis quotes Carlos as saying.

Smith says the gesture “was a cry for freedom and for human rights. We had to be seen because we couldn’t be heard.”

In Russia 2013, the recently concluded World Athletics Championships, where at least two Swedish athletes unveiled their own silent, rainbow-nails protest against anti-gay laws, provided a test run of what the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and Vladimir Putin could expect from athletes and spectators at next year’s Sochi Games.

The IOC has signalled that it will penalize athletes who take their political cue from the Swedish athletes.

Whether the Olympic body cares to admit it or not, the Games are political — from the selection of host countries to the disruption of communities and their social and economic priorities in favour of the Games, not to mention the glaring optics of athletes, dispatched like warriors to the battlefield, to compete for honour and glory for their countries.

What could be more nakedly political than that?

Not to be outdone, Putin, whose signature is barely dry on the legal document that enacted Russia’s nationwide anti-gay gag law, has lately issued his own decree prohibiting “gatherings, rallies, demonstrations, marches and pickets” that are not part of the Sochi Olympics and Paralympics, from Jan 7 to March 21.

To athletes such as American skater Jeremy Abbott — who says it’s “a little rude” to say “bad things about a country that’s hosting the world” — I say you are beyond rude to think only of your medal aspirations while turning a blind eye to your host’s disregard for its queer citizens.

The confluence of the passage of Russia’s anti-gay gag law with the fast-approaching Sochi Games has upped the voltage of the spotlight on the plight of queer Russians, gay rights activist Nikolai Alexeyev argues in an opinion piece entitled “Fighting the Gay Fight in Russia: How Gay Propaganda Laws Actually Only Help.”

“The Olympics is a unique possibility for the Russian LGBT community and the world to be present and have their voice heard,” he says.

What’s the IOC going to do if it is suddenly faced with hundreds of Tommie Smiths, John Carloses and Peter Normans? Discipline and disqualify every one of them?

What will Russian authorities do if athletes begin pulling out rainbow flags during opening and medal ceremonies? Arrest and deport all of them?

Smells like … a self-inflicted boycott.

Let the (gayest ever?) Games begin.

Natasha Barsotti is Xtra Vancouver’s staff reporter.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra