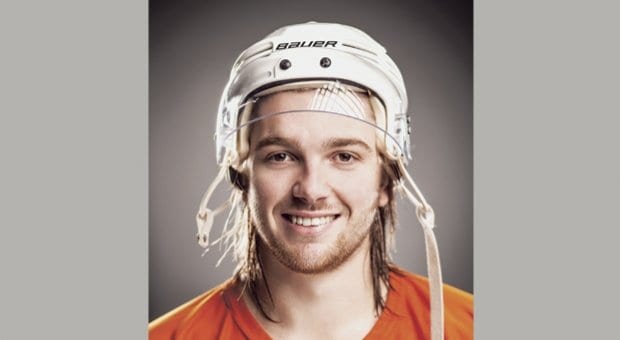

Jono Ceci was already playing with an openly gay teammate by the time he was 17. “Everyone treated him pretty respectfully,” he says. Credit: Shimon Karmel

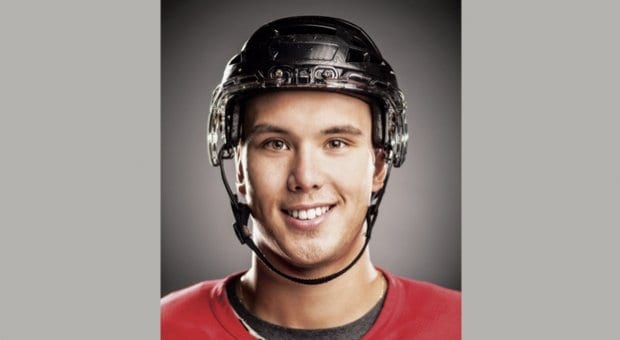

Tyler Mah thinks it’s a question of maturity. “With SFU, the hockey team, we’re older now,” he says, “and I think, with discrimination, you see a lot less of it.” Credit: Shimon Karmel

The SFU team practicing at the Bill Copeland arena outside Vancouver in Burnaby, BC. Credit: Shimon Karmel

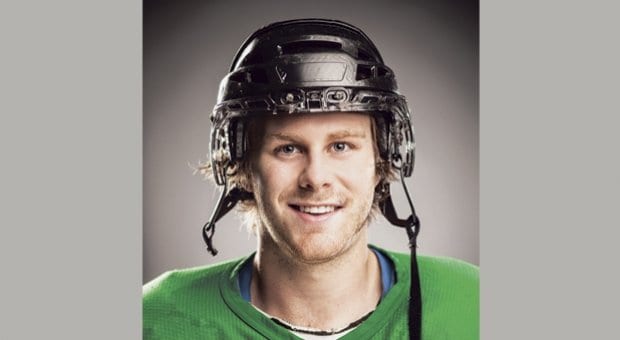

For Josh McKissock, it comes down to kindness and the real meaning of playing with a team.

New this year to the Simon Fraser University (SFU) men’s hockey team, McKissock has been skating since he was four. He grew up in Vancouver’s minor league, then played on junior teams in BC’s Interior and in Alberta, before coming home this fall to play hockey with SFU. Now 21, he welcomes his team’s new partnership with the You Can Play campaign to challenge homophobia in sports.

Though McKissock has never played with an openly gay teammate, he doesn’t hesitate when asked how he’d feel if one of his teammates came out.

“I would support them. You’re all wearing the same jersey; you’re wearing the same logo on the front,” he says. “That’s who you’re playing for. You play for each other. It shouldn’t matter what you are, whether you’re gay, bisexual or straight.”

McKissock may not be your average 21-year-old jock. He’s gruff yet well spoken and articulate. He’s spent years in the traditionally rough-and-tumble, testosterone-fuelled locker rooms of high school, junior and now college hockey, yet he’s clearly compassionate and focused on kindness.

Asked if he thinks a gay player would feel comfortable coming out to his new team, McKissock says, “I would like to think so.

“We play for the university,” he reiterates. “We play for each other. We’re not individuals playing for ourselves.

“I just want to make sure I’m befriending everyone on the team,” he says, asked what he can do to help SFU live up to its newly stated goal of welcoming gay players.

“You just want to be comfortable with one another, know that you’re playing side by side, with a common goal of winning and having fun, rather than discriminating against anyone, whether it’s race or sexual orientation.

“It’s important to befriend everyone and be kind,” he says.

McKissock’s inclusive approach to hockey bodes well for his new team, the first in Canada to reach out to You Can Play in partnership at the college level.

“The guys at Simon Fraser University actually contacted us, said that this is something they believe in,” says Brian Kitts, who co-founded You Can Play more than a year ago with Patrick Burke and Glenn Witman to build bridges between straight and gay athletes.

“Any player, gay or straight, knows the joys of being part of the team,” says Witman, who founded an elite gay hockey team in 2005. “But they also know how homophobic a locker room can be.”

It’s the casual homophobia — the accidental and not-so-accidental anti-gay slurs in the locker room, on the ice and in the stands — that Kitts is hoping to address with You Can Play.

“If we can start locker room by locker room and expand it to other parts of the United States and Canada and other parts of the world, I think that we owe it to ourselves to try,” he says.

“It’s important to change the culture of sport to change society,” he says, “because sports is one of those areas where heroes are made.”

Last year, You Can Play launched with a number of athletes — National Hockey League, professional and some junior, college and even a few high school students — making videos to support the campaign’s slogan: “If you can play, you can play.”

“I think You Can Play is managing to change the culture of sport little by little,” Kitts says. “Nothing changes overnight, but you can start a conversation.”

For SFU centre Jono Ceci, the conversation started earlier than for most.

Ceci has been playing hockey since he was three or four years old. When he was 16 or 17 years old, one of his teammates came out.

“We’d been playing with him for however long it was — 12 years, maybe, already — and we knew him and knew he was a great guy. I mean, whether you’re gay or not doesn’t really matter; you’re still one of the boys.

“Everyone treated him the same as always,” he says. “Just treated him as the same kind of guy.”

The experience shaped Ceci’s perspective on how inclusive a team should be. “Most hockey players are pretty good with that kind of stuff, pretty respectful of everyone,” he believes. “From my experience, hockey players have been pretty good in the dressing room at accepting everyone.”

“I mean, there are guys here and there, just like anywhere, who say maybe not the right thing,” he acknowledges. “But for the most part, they’re all pretty good guys. I mean, there’s a lot of language, for sure, a lot of emotion, but I wouldn’t say homophobic.”

Kitts says it’s critical to reach players while they’re still young.

“Reaching players at the college level is incredibly important because in order to change attitudes you have to start at a fairly young age. The high school and college level — that’s where you really get a chance to start making a difference,” he says.

The earlier you foster an inclusive environment, the more players will develop a comfort level playing with gay teammates and making gay friends — lessons they’ll take with them when they graduate, Kitts says.

Tyler Mah agrees. When the six-foot-three, 23-year-old defenceman isn’t on the ice at the Bill Copeland Sports Centre in Burnaby, where the SFU team practises and plays, he’s coaching young teenagers. He says he sometimes hears inappropriate jokes in the kids’ locker room.

“You have to address that issue right away,” he says. “If you just ignore it, that’s probably the worst thing you can do.”

The kids might not realize they’re saying something that could offend others, he says, so it’s important to tell them.

“I’d say, ‘Look, this isn’t an appropriate way to be talking about anyone or a fellow teammate. You can’t be judging people.’ Usually they kind of look at me and realize that, you know, maybe he’s got a point here. You do, kind of, see the learning: like maybe next time I won’t say something like that.

“If the issue isn’t addressed it could become a problem,” he says, “because then it just becomes acceptable to have that mentality.”

To Mah, it’s about maturity.

“For high school students and athletes, I think it’s important for them to know, while they’re maturing and learning about discrimination, that it’s very important to just be open to everything,” he says.

“With SFU, the hockey team, we’re older now,” he notes, “and I think, with discrimination, you see a lot less of it.”

Younger kids can be ignorant, Ceci agrees. “But as you get older, you just be yourself. People will accept you for who you are, eventually, if not right away. Being honest with yourself is the best thing to do.”

Like Mah and McKissock, Ceci says he’s happy to partner with You Can Play. He thinks it’s important to have openly gay role models in the sports world.

There are probably kids out there who are nervous about coming out to their team, he says. “I think if they see older guys — professional players, college, whatever it is — come out, then they might think it’s okay and do it as well.”

“Partnering with You Can Play for the SFU hockey team is, I think, a really great thing for not only us and You Can Play, but also for the hockey community and the sports community in general,” Mah says. “I think it’s very important for anti-discrimination to be heard and talked about.”

Mah, who has always found the SFU locker room welcoming, doesn’t think the partnership will have a huge impact on the team’s mentality. But it will give the players a chance to show others how welcoming they are.

“I wanted to put together a marketing strategy, a model” that would reflect the team’s spirit, says interim sales and marketing coordinator Réal Maurice Joynt, who first pitched the idea of partnering with You Can Play to SFU’s coach and director of hockey operations this spring.

“These guys are hugely community-driven,” Joynt says, citing, for example, the hours spent mentoring Burnaby minor hockey players, in addition to their own practice and study time. “I’m just pointing out the obvious.”

Head coach Mark Coletta welcomed the suggestion to support You Can Play. It’s about equal rights for everybody, he says, “and it’s good for us to advocate for that.”

This year, the partnership will involve spreading the word, being an advocate, “and making sure that our boys in the dressing room know that it’s equal opportunity for everybody. It doesn’t matter — race, religion, sexual preference. If the person can play hockey, and they’re good enough to play, then we want them,” Coletta says, rephrasing the You Can Play slogan.

“I think that sums it up extremely well,” McKissock says. “Honestly, it’s about on-ice performance.”

If you can perform at the team’s calibre, he says, then “you deserve to be there.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra