The Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society (NSBS) does not have the authority to deny future graduates of Trinity Western University’s (TWU) proposed law school the possibility of articling in the province, a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge ruled Jan 28.

While the BC Christian university is pleased with the ruling, gay lawyers are disappointed, and law societies across Canada — especially in Ontario and BC, which are also facing TWU lawsuits — are mulling the decision.

At the heart of the case is TWU’s community covenant, a document all students must sign that forbids sex outside of heterosexual marriage. In April, the NSBS decided it would block TWU students from its bar admission program unless the university dropped or changed the covenant. TWU took the society to court, arguing that the ban amounts to religious discrimination.

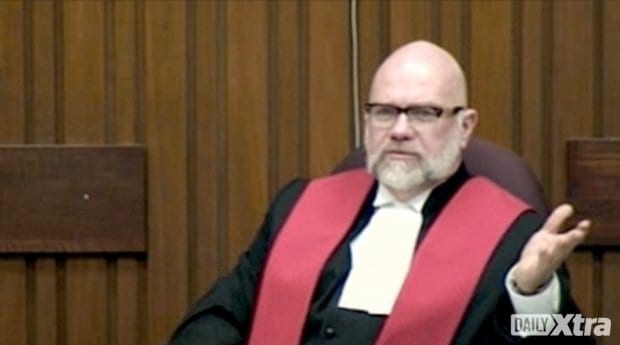

“The NSBS argued that its decision was an effort to uphold the equality rights of LGBT people,” Justice Jamie Campbell wrote. “It was not an exercise of anyone’s equality rights. It was the decision of an entity acting on behalf of the state purporting to give force and voice to those rights. The NSBS is not the institutional embodiment of equality rights for LGBT people,” the judge ruled. “To justify an infringement of religious liberty, the NSBS action has to be directed at achieving something of significance. Refusing a TWU law degree will not address discrimination against anyone in Nova Scotia.”

The NSBS’s requirement that TWU amend its covenant to have its degrees accepted is an infringement of religious freedom and not a trivial matter, he added. “There is a difference between recognizing the degree and expressing approval of the moral, religious or other positions of the institution.” He said a refusal to accept an institution’s legitimacy over concerns about the state’s perceived endorsement of religiously informed moral positions would have a “chilling effect on the liberty of conscience and freedom of religion.”

The decision is the first court ruling in Canada on whether provincial legal-profession regulators have the power to deny TWU’s ability to operate a law school or make decisions on how law schools operate.

Campbell questioned whether the NSBS had “reasonably considered” whether its decision, and how it affected religious freedom, is consistent with Canadian legal values of inclusiveness, pluralism and the respect for the rule of law. “In that sense, it is a value judgment,” he said. “I have concluded that the NSBS did not have the authority to do what it did. I have also concluded that even if it did have that authority, it did not exercise it in a way that reasonably considered the concerns for religious freedom and liberty of conscience.”

Campbell said the NSBS could act only under the authority of the province’s Legal Profession Act. “That act does not give the NSBS the power to require universities or law schools to change their policies. Its jurisdiction does not reach that far,” he ruled. He noted that the Federation of Canadian Law Societies decided in December 2013 to recognize TWU law degrees.

“There is nothing wrong with TWU law degrees or TWU law graduates,” he said. The central issue was the covenant, over which the NSBS has no authority, he noted. “That is no different than deeming a law degree not to be a law degree unless the university amended any number of other policies that are not reflected in the quality of the graduate,” Campbell said. “Those could include tuition policies, harassment policies, affirmative-action admission-quota policies or tenure policies.”

“The legal authority of the NSBS cannot be extended to a university because it is offended by those policies or considers those policies to contravene Nova Scotia law that in no way applies to it,” the judge said. “The extent to which NSBS members or members of the community are outraged or suffer minority stress because of the law school’s policies does not amount to a grant of jurisdiction over the university.”

Moreover, Campbell said, the NSBS had characterized the covenant as unlawful.

During December arguments in the case, NSBS lawyer Peter Rogers called TWU a “rogue law school” and compared it to all-white schools in the United States. “If we validate Trinity Western University’s law application, we validate homophobia, and the message to LGB youth is that they do not matter,” Rogers argued.

Campbell said the covenant “may be offensive to many, but it is not unlawful. TWU is not the government. Like churches and other private institutions, it does not have to comply with the equality provisions of the Charter. It has not been found to be in breach of any human-rights legislation that applies to it.

“The Charter is not a blueprint for moral conformity,” he continued. “Its purpose is to protect the citizen from the power of the state, not to enforce compliance by citizens or private institutions with the moral judgments of the state.” Campbell said people have a right to attend a private religious university that imposes a religiously based code of conduct. “That is the case even if the effect of that code is to exclude others or offend others who will not or cannot comply with the code of conduct,” he added.

“Learning in an environment with people who promise to comply with the code is a religious practice and an expression of religious faith. There is nothing illegal or even rogue about that,” Campbell ruled. “That is a messy and uncomfortable fact of life in a pluralistic society. Requiring a person to give up that right in order to get his or her professional education recognized is an infringement of religious freedom.”

Campbell said that when evangelical Christians study law, “they are studying law first as Christians.” Attending such an institution is an expression of their religious faith, he added. “That is a sincerely held belief, and it is not for the court or for the NSBS to tell them that it just isn’t that important.”

NSBS president Tilly Pillay said in a statement the society is reviewing the ruling.

“We appreciate that Justice Campbell dealt with this matter very quickly and comprehensively. We are analyzing the decision and will review it with our legal counsel before we can determine what the next steps might be,” Pillay said. “There is much to consider.”

TWU spokesperson Guy Saffold says the decision is important not only to TWU’s effort to launch a law school, but because it “sets an extremely valuable precedent in protection of freedoms for all religious communities and people of faith in Canada.”

“We’re pleased [the judge] found the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society acted outside of its jurisdiction,” he adds. “He made the interesting statement that societal changes haven’t affected the underlying principles of the law. That’s our position in the case.”

Those underlying principles were expressed in a 2001 Supreme Court of Canada ruling in Trinity Western University v British Columbia College of Teachers. That ruling upheld TWU’s right to teach Christian values to would-be teachers and to insist that incoming students sign the covenant. The high court found TWU teacher program graduates are entitled to hold “sexist, racist or homophobic beliefs” as long as they don’t act on them in the public school classrooms to which they might be assigned.

Saffold says the issue is about how people live together with respect and appreciation for each other. “These are difficult and controversial issues,” he notes. “It would be great if we all agreed, but we have deeply held, sincere convictions.”

Amy Sakalauskas, of the Canadian Bar Association’s Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Conference (SOGIC), calls the ruling disappointing. She says many SOGIC members had worked with the NSBS on the case and would be supportive if the society seeks to appeal the ruling. “In any decision of this length, anyone would say there’s a lot of room for appeal,” Sakalauskas tells Xtra.

The future of the BC law school, however, hinges on TWU’s accreditation by the government as a degree-granting law school in BC. Earlier in December, BC’s former minister of advanced education withdrew his approval of the law school after an October vote by the Law Society of British Columbia (LSBC) not to recognize students.

TWU has launched a suit against the LSBC but not the government.

LSBC spokesperson Ryan Lee says in a statement to Xtra that the society is reviewing the ruling. “We are following the proceedings in other jurisdictions in light of the litigation involving us currently underway in BC,” Lee says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra