“L’humour c’est de s’interdire à rien,” cartoonist Georges Wolinski once said, before he was assassinated with seven of his Charlie Hebdo colleagues at an editorial meeting in their Paris office Jan 7.

Translated it means “Humour has no prohibitions.” No subject is too sacred to satirize, to critique.

In the deluge of coverage following the murders, it can be easy to get distracted by the manhunt, the logistics of the shootings, the assassins’ identities, what they learned where and from whom. It can be equally essential to monitor the predictably deplorable anti-Muslim backlash and government justifications to suspend civil liberties for more anti-terrorism measures.

But at the heart of this story lies freedom of expression and the beating it’s taken on multiple fronts since fear seeped into our social consciousness and sapped our courage to discuss all topics openly.

Mainstream media are obsessed with tracking terrorism threats yet shy away from in-depth discussions of what scares us into silence and, most importantly, how to openly communicate with each other instead, to foster truly pluralistic societies where no subjects are taboo and we can learn to offend without excluding each other.

Learning to offend and especially to feel offended without resorting to shaming or silencing tactics doesn’t come easily. In our own community, we are quick to try to silence each other as well as perceived anti-gay or anti-trans enemies when we feel threatened or offended — anyone who dares to challenge the rights we’ve painstakingly carved for ourselves or sometimes, simply, to question established or emerging “truths.”

Rather than celebrating open discussion and the importance of genuine debate, we live in a society steeped in fear, distracted by manhunts and vacuous celebrity gossip, and generally unwilling to engage in painful discussions of how to address long-standing power imbalances and emerging incompatibilities to try to find ways to coexist without squashing each other.

“In the face of ambient nervousness, our fear is to be too cautious, too reasonable,” Charlie Hebdo contributor Laurent Sourisseau (known as Riss), injured in the Jan 7 attack, once remarked.

I’ve certainly felt the chill: don’t question this, don’t challenge that. But if Charlie Hebdo’s team taught us anything, it’s to fight the chill and critique without fear.

Riss knew that, as he put it, fundamentalists have no sense of humour. But that didn’t stop him or his colleagues from challenging them all, especially the segment of Islamic fundamentalists who launched violent protests around the world after a Danish newspaper dared to represent and even caricature Muhammad in 2005. Charlie Hebdo reprinted the vilified cartoons and added its own cover: a weeping Muhammad saying, “It’s hard being loved by jerks.”

The magazine took equal aim at everybody: no topic was off-limits, they said, and none should be. And no one was exempt, fear of reprisals be damned. “I don’t see why we can’t critique all ideologies,” Jean Cabut (Cabu) said.

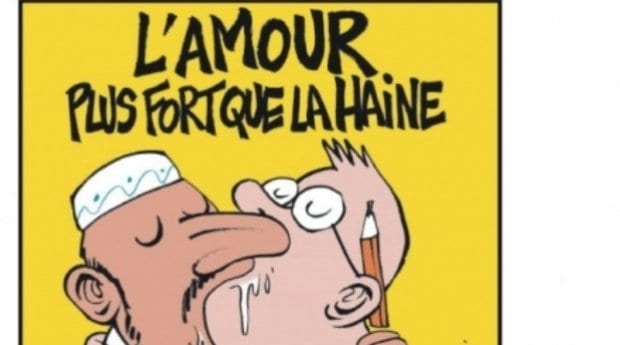

They didn’t back down when their office was destroyed by Molotov cocktails for another Muhammad cover in 2011. With his now-famous retort, “I prefer to die standing than live on my knees,” editor Stéphane Charbonnier (Charb) hired bodyguards and put another Muslim man on the cover — this time kissing a male cartoonist.

No doubt the cover was designed to needle their opponents and take aim at yet another taboo — that was, after all, the satirists’ raison d’être — but like most of their work, it also made a profound point: “Love is stronger than hate.”

Taboos don’t spread love; they create barriers and block discussion. If we truly want to build a pluralistic society that sets love free, we can’t yield to anyone’s demands for silence on any topics — whether out of fear, misplaced sensitivity or shame.

Je suis Charlie, and I won’t be silenced.

Robin Perelle is the managing editor of Xtra in Vancouver.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra