“Where do any of us come from in this cold country? Oh Canada, whether you admitted it or not, we come from you we come from you. From the same soil, the slugs and slime and bogs and twigs and roots. We come from the country that plucks its people out like weeds and flings them into the roadside […] We come from cemeteries full of skeletons with wild roses in their grinning teeth.” – Joy Kogawa, Obasan

When the first Chinese migrant workers came to Canada in the 1800s they believed that the bones of any man who died in this cold cruel land had to be sent home to be buried in his ancestral village. Otherwise, his spirit would become a “hungry ghost,” a lost soul doomed to wander this barren place for eternity.

There were many unfortunate souls — workers whose broken bodies were lost in the landslides created by dynamite used to build the Canadian Pacific Railway, poor people whose families could not afford the passage back to China — who suffered this fate. They still walk among us, the old-timers say.

Today in the 21st century, I can’t help but think that maybe it’s me and my fellow second, third and fourth-generation Chinese Canadian queers who are the hungry ghosts. We are destined live in the space between homelands: Too queer for Chinatown. Too “white-washed” for the urban gay scenes of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan — places where most of us have never lived, anyway. Too Asian for gay villages across the continent, which love their pretty white boys so much.

Three generations of stories slipped through the cracks in the words between us, two whole lifetimes lost in translation.

My Yeh Yeh, paternal grandfather, died six years ago. We were close in the way that relatives who have always known each other but never really spoken are both close and distant at the same time.

I never told him I was trans, which I’m not certain he would have understood anyway. I don’t know if there’s a word for “trans” in toisanhua, my family’s ancestral tongue.

Contemporary Cantonese and Mandarin have developed a variety of roughly equivalent terms, but my Yeh Yeh was a working-class man who grew up in rural China during the Civil War and the Japanese invasion, and never attended high school. He wouldn’t have learned those words, or so I assume. I guess I assume a lot of things about Yeh Yeh.

The truth is, I never really learned to speak Chinese very well in any dialect. I knew Yeh Yeh from the time I was born, but our conversations were limited to a handful of broken sentences here and there in three different languages — English, Cantonese, toisanhua. Three generations of stories slipped through the cracks in the words between us, two whole lifetimes lost in translation.

It didn’t matter that I was now a girl. I was also, still, the eldest son. I had a duty to fulfil.

Still, some things stay sacred, no matter how far from home you go. In Chinese tradition, when an elder passes away, the eldest son of each child of the departed bears the coffin at a funeral — sons because it is a man’s patriarchal responsibility to literally carry on the family line. For my family, that was me.

It didn’t matter that I was now a girl. I was also, still, the eldest son. I had a duty to fulfil, a role to play, an obligation of blood. This is Chinese love, the truest love.

I want to take a moment here to note that white people are always asking queers of colour to tell them the “ethnic gay story.”

“Was it hard to come out to your family?” They ask eagerly, eyes shining with hunger. “Are they very traditional, which is to say, queerphobic?” (It is taken for granted that the traditions of non-white cultures are queerphobic.)

Liberal white people love the ethnic gay story. It confirms their belief in the superiority of whiteness and assuages their sublimated guilt over the queerphobia and racism that are still rooted deep within white-dominant, colonial Western society.

What the ethnic gay story misses is that the queer children of diaspora are not the passive victims of our villainous, ignorant families; or at least, not in the way that whiteness likes to imagine us. Our relationships with our blood, our selves, are more complicated than that.

What the ethnic gay story misses is that the queer children of diaspora are not the passive victims of our villainous, ignorant families.

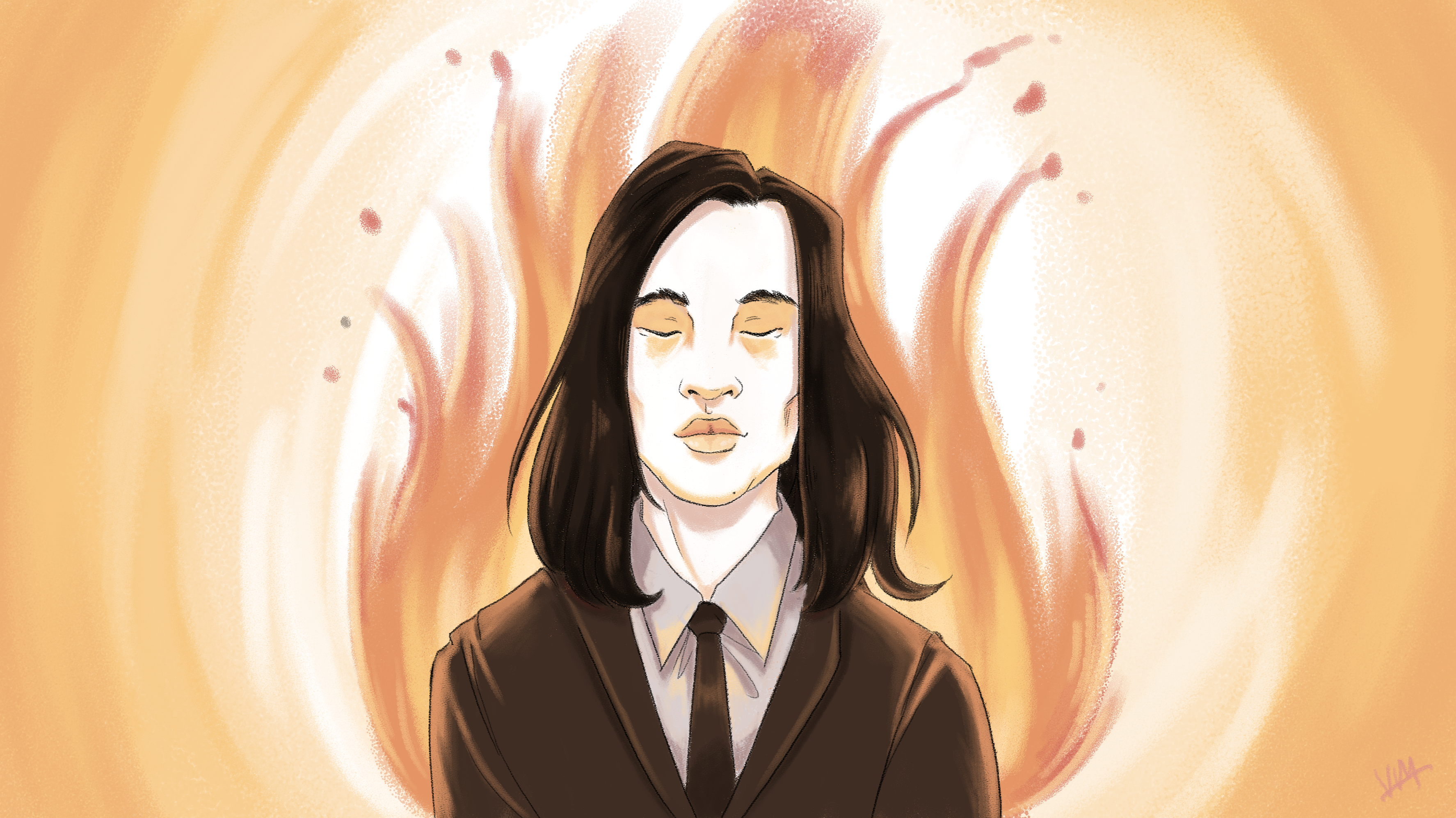

So I don’t believe that when I flew to Victoria for the funeral, leaving my punk queer femme clothes behind, that I was being forced to leave my womanhood behind as well. As I washed off my makeup and dressed in a black suit and tie, for all the world my parents’ son again, I was not choosing between being trans and being Chinese. What I chose was the strength of my family’s values — loyalty, lineage, the fulfilment of duty, gratitude to one’s elders — and the magic of queerness: transformation, change, adaptation and resiliency.

So perhaps it isn’t as strange as it seems that when I took the weight of the rosewood coffin that held my Yeh Yeh’s body in my gloved hands, lifting it up with five of my male cousins, I felt stronger and more certain in who I was than I ever had in that time of my life.

In that moment, on that island an ocean so far away from where my ancestors were born, I knew who I was: My mother’s daughter. My father’s son. A woman as Chinese as they come, as strong as the iron and the bones my ancestors lay in the ground to build the spine of this colonized nation, as queer as new moon rising.

It’s hard to walk with ghosts on your shoulders, but when you learn to listen to what they are saying, you realize that they are telling the story of who you are.

A traditional Chinese funeral ends with a rite of cleansing. A fire is lit in front of the doorway of the departed’s home, and the family in mourning jumps over the flames before re-entering the house.

The flames purify the living of bad luck, and the rising smoke lifts what remains of the departed one’s spirit up into heaven. This is an old, old custom — older than the arrival of Christianity in Asia, older than the spread of Buddhism into China, older than Taoism.

In that moment, on that island an ocean so far away from where my ancestors were born, I knew who I was: My mother’s daughter. My father’s son.

My family approximated this by lighting some rolls of newspaper on fire in my Yeh Yeh’s driveway. Picture it: 40 Chinese people, spanning four generations, dressed in funeral wear, standing around a pile of burning paper in a driveway in the middle of suburban Victoria.

As I prepared to make my own leap over the fire, I bowed my head and closed my eyes. I thought about Yeh Yeh, the things I would never say to him, the things he’ll never know about me. In the distance, I could hear the sound of sirens.

And then the sounds weren’t so distant.

Racing the down the street, sirens blaring and lights ablaze, came a small fleet of fire trucks and police cars. They drew up to my Yeh Yeh’s house, and several uniformed officers jumped out.

The elders of the family recoiled, scandalized, the little kids darted behind their parents, and those of us in our 20s and 30s stepped forward protectively.

As it turned out, the neighbours had been watching through their windows, and someone had called 911. Lord knows what they must have said. An Asian cult in formal wear is performing a Satanic ritual in someone’s front yard. My grandparents had lived in that suburb with their white neighbours for over 20 years, only to have my Yeh Yeh’s last rites desecrated by racism.

I like to think my Yeh Yeh would have laughed to hear what had happened at his funeral. I like to think he’d acknowledge what I did for him with quiet approval. I like to think that someday, I’ll tell him that story in the place where the ancestors live, a place between the worlds, where every story can be told and understood.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra