The question has been buzzing angrily through the gay community for months now: Did the Crown make a mistake when it charged Aaron’s Webster’s alleged killers with manslaughter instead of murder?

Last month the buzz reached a crescendo after a Vancouver judge threw the book at the first youth arrested in the case, called his crime a gaybashing and sentenced him to two years in jail plus a year of house arrest. (The youth, who can’t be identified because he was under 18 at the time of the offence, had pleaded guilty to manslaughter several months earlier.)

While the stiff sentence brought smiles to many gay faces, it also sparked a renewed interest in the murder vs manslaughter question. “If the youth got the maximum penalty for manslaughter why wasn’t he just charged with murder in the first place?” some people asked.

It’s a complicated question. To begin to answer it, I turned first to the Criminal Code of Canada to look up the difference between manslaughter and murder.

Here’s what I found: Murder is defined in Canada as the act of killing someone, coupled with the intention to kill that someone. In other words, it’s more than just the act-it’s the state of mind.

Let me back up a step. Whenever a person kills another person, the law calls it a homicide. Then the law tries to gauge how serious the homicide was. The first question it asks: Was Person X culpable for Person Y’s death? (Culpable is legal-speak for responsible.) If the answer is yes, the law basically tries to figure out how culpable. That’s where murder and manslaughter come in.

In order to measure the degree of culpability, the law applies a grid of rules and definitions to the incident at hand. If the killing happened like this, it’s one type of homicide, like that and it’s another. Manslaughter and murder are the two most serious types of culpable homicide-they fall side by side at the end of the continuum.

Murder is the very end of that line. For a homicide to count as a murder, it has to match the following definition: The perpetrator has to A) kill the victim, and B) consciously intend to kill the victim. Criminal act plus criminal intention equals murder.

That’s the first definition of murder. Now here’s the second: It’s also murder when the perpetrator A) kills the victim and B) intends to cause the victim bodily harm with the knowledge that said harm will likely lead to death.

In other words, murder means the perpetrator consciously meant to take a life or knew that death would likely result from his or her actions-and did it anyway.

Now let’s look at manslaughter. Canada’s Criminal Code says it’s manslaughter when the perpetrator kills the victim without intending to, and without knowing that his or her actions will likely cause death.

Bottom line: The difference between manslaughter and murder lies in the mind of the killer. If the perpetrator didn’t mean to kill-and didn’t know that death would likely result from his or her actions-then it’s not murder.

End of story.

Well, not quite. As gay lawyer Garth Barriere points out, it can be very difficult to prove what a perpetrator actually knew and intended at the time of an incident. Actions might be obvious, but thoughts are often hard to decipher. They often have to be inferred from whatever clues the perpetrator leaves behind. If, for example, the killer happened to yell in front of a crowd of witnesses that he was going to kill the victim, then that’s a pretty good clue as to his state of mind. But killers aren’t always so blatant, and witnesses aren’t always listening.

So what clues do we have about the youth who was recently sentenced for killing Aaron Webster? We know from Judge Valmond Romilly’s now-public sentencing decision that the youth confessed to being one of several people at the scene of Webster’s death.

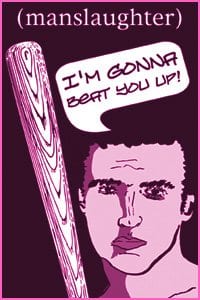

We know that the youth confessed to hitting Webster twice with a baseball bat, once on his upper back and once on his leg.

We also know, from the youth’s confession to police, that he says he never intended to kill Webster-beat him up, yes, but not kill him.

These clues suggest that the Crown was right to charge the youth with manslaughter, after all. The youth explicitly told police he had no intention of killing Webster, and his recollection of that night shows no obvious knowledge that his actions would likely lead to death.

Of course, the youth could have lied to police about his intention, especially after waiting a year and a half to confess. But the Crown can only build a case on what it can prove beyond a reasonable doubt. And apparently it could not prove that the youth had any intention to kill Webster.

And that makes it manslaughter-not murder.

As Crown spokesperson Geoff Gaul explains, he and his colleagues can only press charges they can support in court based on the evidence they have at hand.

“If there’s evidence that makes out a charge of murder, then we present that,” he says. “We have an obligation to proceed on what we believe is the appropriate charge based on our assessment of the available evidence.”

It would be improper for the Crown to lay a charge it couldn’t prove in court, Gaul continues.

“I am very confident” that the experienced, senior counsel in this case laid the correct charge, he adds.

“Crown counsel are aware of, and sensitive to, community needs and desires but we cannot allow that to impact upon our professional obligation to assess the available evidence that we have,” he concludes.

***

But the story doesn’t end there. It is, after all, a complicated question. Let’s go back to Judge Romilly’s sentencing decision. In paragraph 43, Romilly says that “the accused by using baseball bats and golf clubs to beat the victim must have been aware that death could result from those hard objects coming against a fragile body with the obvious force that was applied, and were really reckless as to the consequences of their actions.”

Sound familiar? It should. Romilly comes within a hair of reciting the definition of murder.

Remember, murder means the killer meant to kill-or at least knew that his actions would likely result in death and did it anyway. Romilly says the youth must have known his actions could result in death and did it anyway.

It’s close but it’s not murder, Romilly’s ruling suggests, placing the killing firmly at the most serious edge of manslaughter-right next to the place on the homicide continuum where murder begins.

So here’s the question: If the youth’s actions were indeed so close to murder, should the Crown have simply charged him with murder and let a judge or jury decide what was in his mind at the time of the incident?

That’s possible, says lawyer Barriere-especially in this case where the distinction is so fine.

But remember, he cautions, had the Crown pressed a charge it couldn’t prove and lost its case, the youth would have simply walked free.

It’s a tough judgement call, Barriere says.

And it’s fair for the community to question that call now, he adds.

Barriere says he doesn’t know if the Crown made a mistake when it sought the weaker manslaughter charge. But the Crown did get “dressed down” by the judge for failing to characterize the killing as a hate-motivated gaybashing, Barriere points out. So if the Crown made one mistake, did it make two? Did it press the wrong charge to begin with? Did it consistently shy away from the gay nature of this case and downplay its facts?

Gaul says no. The Crown pressed the charge that it could prove in court, he repeats-homophobia had nothing to do with it. “The fact that Mr Webster was a gay man played no role in our determination of what the appropriate charge should be in this case,” he says.

But some community members aren’t so sure. As recent news reports indicate, they still think the charge should have been murder.

Barriere says he just doesn’t know. But these are questions worth asking, he reiterates, adding that it’s important to hold the Crown accountable.

Besides, he continues, even if the Crown was right to pick manslaughter-which it may well have been-the community still has a right to question the charge and the whole legal framework from which it emerged.

People are responding emotionally to this attack, he says. They’re looking at the viciousness of this particular assault by this particular youth and saying, “that looks and smells to me like murder.”

And there’s nothing wrong with that kind of emotional response, Barriere continues. People can describe a vicious attack any way they want. “But the law isn’t so flexible.” The law has precise, rigid rules and definitions. It operates on fine distinctions between categories-distinctions that many non-lawyers have a hard time accepting.

Some people may argue that those fine distinctions and categories should be abolished altogether, Barriere continues. They may call for a criminal system where all acts that result in death get the same high penalty. And that would be legitimate, too.

But Barriere says he prefers the system we have in place right now. The law should treat people differently based on their different intentions, he maintains. If you know your actions could kill and you assault someone anyway, you should be held to a higher degree of accountability than someone who didn’t know their actions would likely lead to death.

People who kill without meaning to should still be held responsible for their actions, he continues, but not necessarily for murder.

Murder carries an automatic life sentence and a high social stigma, he points out. It shouldn’t be handed down to someone who genuinely never meant to kill and didn’t realize his actions would be deadly.

The question is: What did the recently sentenced youth know?

We may never know for sure.

All we know for sure right now is that the Crown charged the youth with manslaughter, the youth pleaded guilty to manslaughter, and the judge gave him the maximum sentence for manslaughter.

Could the Crown have successfully made a case for murder instead?

We may never know, Barriere repeats. But the community is entitled to ask why the Crown didn’t even try.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra