Uganda’s LGBT community is seemingly in for some déjà vu all over again, with reports that the country’s lawmakers are angling to bring back the court-nullified Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) for a revote.

Nicholas Opiyo, one of the lawyers representing the nine petitioners who challenged the act’s constitutionality, and opposition MP Fox Odoi take great pains to stress that bringing back the voided legislation would not stand up to legal scrutiny. If the government is bent on having such a measure in force, it will have to start from scratch — and that means jumping through all the parliamentary procedural hoops, including getting leave to bring forward a new anti-gay bill.

If done by the book, it’s a process that could take at least two years, Odoi estimates. “That is the law; there is no shortcut.”

It’s a law that many determined legislators seem eager to overlook. According to Odoi, “well in excess” of 200 Ugandan MPs have signed a petition calling for a revote on the legislation.

“The attempt by MPs to ‘retable’ the AHA without starting de novo is an illegality dat will be challenged. There’s no bill in de hse 2 retable,” Opiyo recently posted on Twitter.

“They think it’s fashionable to be homophobic,” Odoi says.

With or without a bill on the table, the homophobia that fuelled MP David Bahati’s 2009 private member’s bill remains pervasive — and persistent.

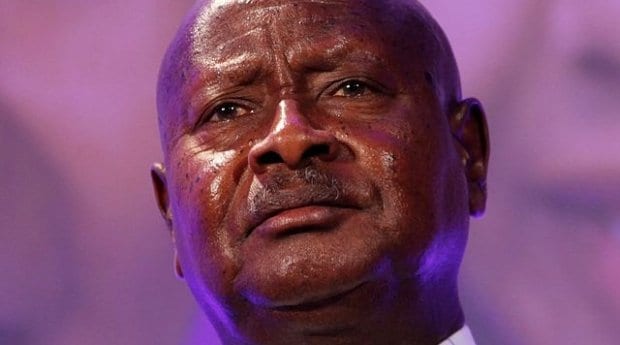

When President Yoweri Museveni signed Bahati’s now-nullified bill into law in February, he played Janus with the issue: one side of his face telling the Ugandan electorate, the potent Pentecostal movement and their American evangelical supporters the anti-gay rhetoric they wanted to hear, while the other attempted to appease donor countries and organizations like the Robert F Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights — stalling tactics, as it turns out, to give the false impression that he was showing good leadership, restraint and some modicum of reason.

In January, for the consumption of RFK Center delegates and the rest of the international community, Museveni called the bill “fascist.” A month later, he was scrawling his signature on the document that would be invoked to further discriminate against the country’s already-besieged LGBT population.

Looking at the crowds that turned out for a five-hour rally to thank him for “saving the future of Uganda,” Museveni made the right opportunistic call as the 2016 elections approach.

Whether the AHA is resurrected through illegal means in the short term or through a drawn-out process in the long term, Opiyo and Odoi argue that surrendering to the status quo is not an option.

And it bears repeating — not so much to the damaged, corrupt and dissent-intolerant Museveni regime, but to those who intend to challenge his almost three-decade hold on power.

“We must engage the homophobes every day,” Odoi insists. “We must make sure they know they are as wrong as apartheid South Africa was; they are as wrong as the people who engaged in the slave trade.”

Natasha Barsotti is Xtra’s Vancouver staff reporter.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra