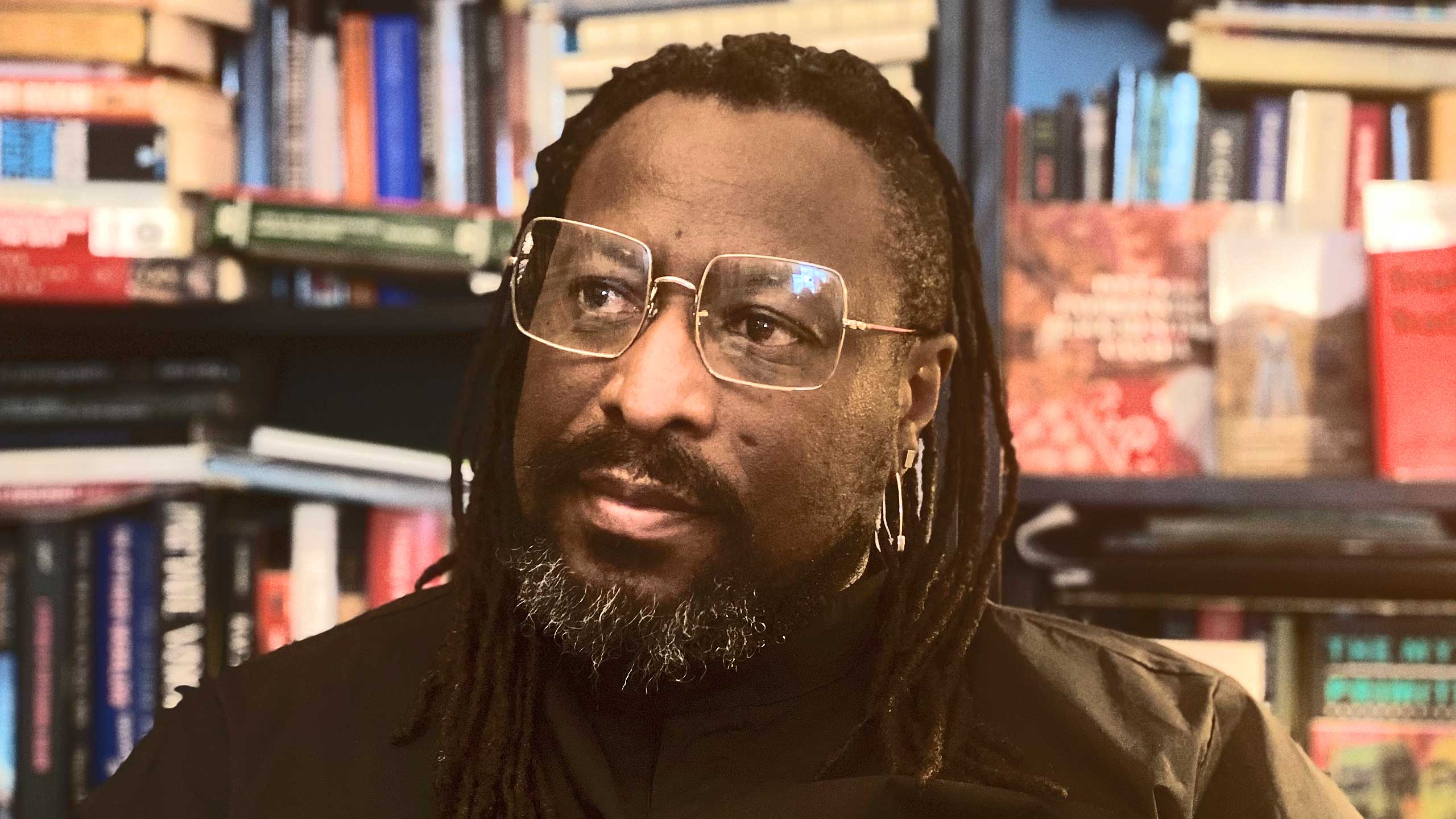

Rinaldo Walcott wants you to look ahead. A writer, educator and cultural commentator, Walcott is a professor in Women and Gender Studies and has taught at the University of Toronto for 20 years.

On Friday, Oct. 29, Walcott will speak at the 2021 health summit hosted by the Community-Based Research Centre (CBRC), a community-led research and advocacy group in Canada that promotes the health of gay, bi, trans, Two-Spirit and queer men. Called Disrupt and Reconstruct, the summit takes place online from Oct. 27 to 29. Walcott’s talk will focus on the parallels between the current pandemic and the AIDS epidemic. As we start to re-emerge into public life, Walcott is exploring how communities can rebuild what the pandemic has destroyed, and asks us to consider: “What can we do with what we have?”

Xtra caught up with Walcott before the conference to chat about where LGBTQ2S+ people can go from here.

Let’s start with the basics. What do you plan on talking about at the upcoming conference?

During the conference I’m going to be talking about three main things: first is, given that we’re still living in COVID-19 times, I want to tease out the similarities and differences between the current period and the AIDS crisis. One of the things that I want to point out is the activism that grew the moment that queer communities were abandoned to deal with AIDS on their own. Queer people had to engage in forms of activism that have since produced a very different queer life—one that wouldn’t have been imagined before AIDS.

The second thing I want to do is critique identity and the limits of identity claims. Let’s talk about how being queer is not sufficient to articulate a politic, or a new vision and future for this world—especially in the context of all of the things that COVID-19 has revealed to us.

Finally, I want to tackle the question of values. What kinds of political values queer-identified people should be thinking about, engaging in debate about and having conversation about. Those values should go well beyond the question of identity, the question of sexuality. How should queer people, especially queers living in the wealthy developed world, think about what their political participation should look like?

These are all big questions. The idea that identity politics won’t save us seems to come up more frequently as the pandemic laid social and economic inequalities bare. Can you talk a bit about what the limits of identity are for you?

Identity can be useful to a point. We saw that with the unleashing of AIDS, and the way in which it was understood as an identity-defined illness. I mean that it was supposedly queer people who contracted HIV, and then it was Haitians, then it was intravenous drug users and on and on. All of those people who were marked in that way organized around AIDS and around the way governments and health care systems abandoned them.

That led to a bunch of things that people take for granted now—like the fact that your partner can visit you in a hospital,that they can have access to your pension, they can be on your insurance. All of these things happened within a really short period because people mobilized identity to push back against the brutality that they were experiencing.

But the problem with queer identity is that it only tells us something about what somebody’s desire or sexual practice might be; it doesn’t tell us much more than that. One of the things that we’ve begun to do is to align queer identity with the assumption that people necessarily have a progressive type of politics. And we now know that not to be true, right? When we see somebody like Pete Buttigieg sitting in government, we know this not to be true.

Remember when he wanted to bring back conscription?

Exactly. So as queers, we have to be clear about what kind of politics we stand for. Do we stand for the rabid individualism of neoliberalism? Or do we stand for a political system that is about collectively securing the resources for all people to live the best possible life? Who you sleep with, who you desire—that doesn’t immediately define the answer to those questions.

I find your use of the word “values” interesting. Typically when we hear the term in relation to LGBTQ2S+ people, it’s being used against us, as in “a threat to family values.” In your mind, what “queer values” should we be striving for?

I want queer and trans people to take the term “values” and reshape it away from the patriarchal, white supremacist clutches of “family values.” But I also want to reshape it away from capitalist value. There have been fleeting moments where queer radicals were willing to offer a different account of what the world should be since the 1970s, and a product of that was sexual liberation. It really shaped a lot of what we live now and take for granted. And I think what has happened in the interim is that queer people—especially white queer identified people—have been refolded into all of the logics of white supremacy.

Part of what I want to suggest is that those of us who self-identify as queer continue to have a different account of what the world might be, and that our values should be about collective care for each other. Those values shouldn’t be about valuing life based on its proximity to whiteness. Those values shouldn’t be tied to economic extraction.

We can’t simply look at someone who claims to be queer and decide we’re going to support them—regardless of their politics—based only on their sexuality. We need to be really clear about what kinds of values we support, what kinds of values we’re willing to practice.

Anecdotally speaking, I’ve noticed the profound unfairness of the pandemic has radicalized some people—or, at least, opened some people up to more radical politics. We know that tends to happen in moments of political upheaval or uncertainty, but why do you think that moments of queer radicalism have been, as you say, fleeting?

Primarily, I think it’s because white queers got reintegrated into the logic of white supremacy. White queers were allowed to become the visible spokespeople for who we are and who we might be. That’s the selection process of white supremacy. The selection process made sure that radical white queers, socialist white queers, radical white lesbians of the ’80s and ’90s disappeared from the public eye.

Largely, white men (with a smattering of white lesbians) were offered the opportunity to be representative figures if they behaved in a suitably normative way. And those representative figures of queerness could also chastise the rest of us for still engaging in wild and nasty practices—you know, like having sex in washrooms and parks and those kinds of things.

Let’s take a second to talk about wild and nasty practices: we’re seeing a desexualization and, in my view, a sanitation of queerness as of late. What roles do pleasure and desire play in where we as LGBTQ2S+ people go from here?

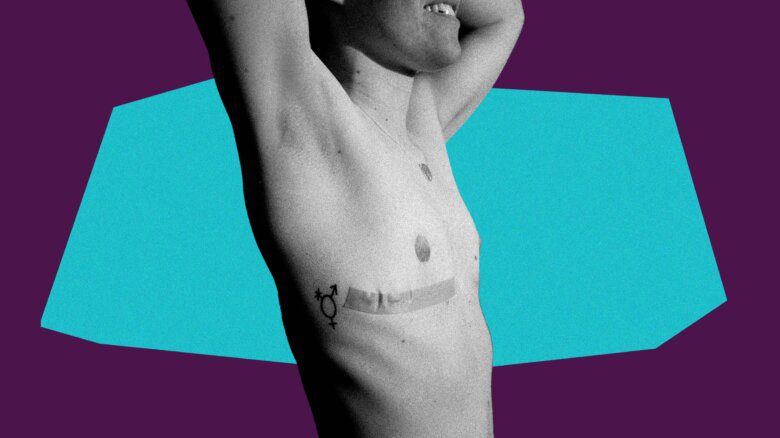

Pleasure and desire are key to what I’m saying about values. Homonormativity is not about liberation. It’s about being folded into the norm. It’s really easy to trot out a two-mom or two-dad middle-class household as a sign of progress and of change having occurred. But what about for trans people, non-binary people, all the people we police for trying to pursue the kind of life they want to pursue, even when they’re not hurting anyone?

For me, queerness is about respect and dignity for each other. And again that call for a different kind of logic. That means, then, the question of who gets to have access to homes, who gets to have access to health care, who gets to have access to livable wages—those are the kinds of things that queer people need to be thinking about.

What will it take not to just conceptualize these values, but to live by them?

The fact that we still talk about the concept of “queer communities” is a powerful effect of nonheterosexuality shaping contemporary modern life. That’s a gift in and of itself. So if we still seem to imagine ourselves as communities of queer people, what can we do with that? We have the responsibility to use the collective power we now hold to shape the world—maybe not the world that we will get to live in but the world that comes after us, to build the foundation for a different kind of world.

We have to come together in social meetings to engage our activism, to engage with governmental organizations and so on. We can’t be reproducing the world that we have—a world that we know is totally insufficient, that’s harming many people, that simply can’t survive if we continue on as is. I’m of the belief that each generation finds what its mission is and engages that mission in the way that is most powerfully suited to them. The climate emergency, for example, is one that exceeds the question of sexuality and how we identify.

So instead we need to ask: How can we harness this collective power to begin to put into place the conditions for a different kind of the world?

I want to imagine and build that different world, but I don’t think I’m alone in feeling, sometimes, that it’s just not going to be possible for my generation. You mention the climate crisis. After the IPCC report was released this past summer, I was just like, “Well, we’re fucked.” How can we avoid that nihilism and keep building?

I don’t think we need to avoid nihilism, we just can’t sink to its lowest points. And what that entails is thinking differently about what community means. The fantasy of queer communities is that we all share something in common. So often that fantasy goes awry, you know, when Black people arrive, when other people of colour arrive, when people who refuse the categories of gender arrive.

There are all kinds of ways in which the fantasy falls apart. Part of what we have to do is to be really realistic and acknowledge that while the thing that supposedly holds us together doesn’t entirely hold, we can still care for each other in profound ways.

Rinaldo Walcott’s talk will take place at 1 p.m. PT on Oct. 29, 2021. You can register to attend for free here.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra