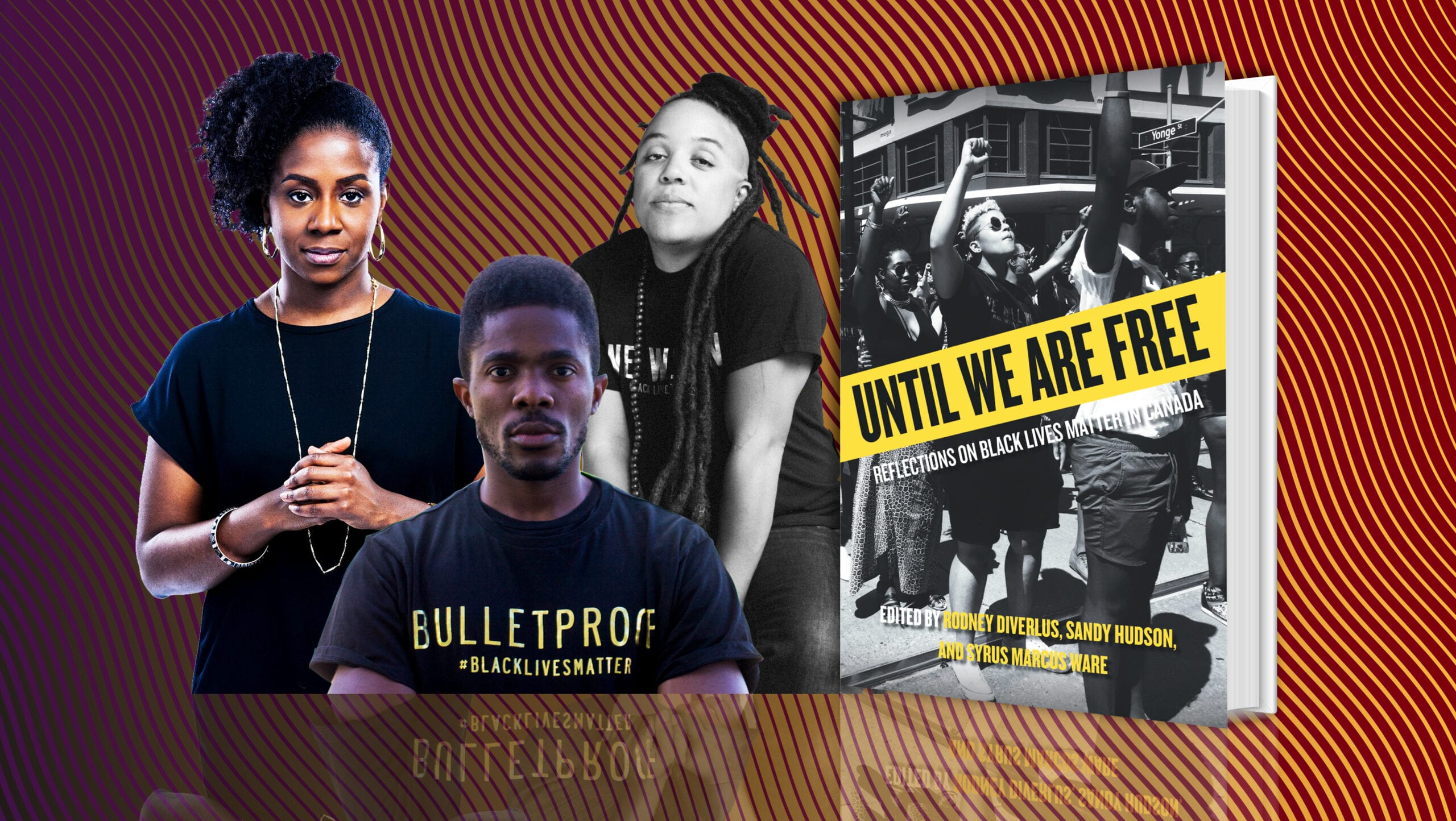

Following the killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, the Black Lives Matter movement quickly became a symbol of injustice towards Black people in America. The movement quickly spread to Canada, where generations of Black communities and activists spoke about the country’s problem of anti-Black racism, debunking the myth about Canada’s politeness and inclusivity. Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada, edited by Sandy Hudson, Rodney Diverlus and Syrus Marcus Ware, contains writing by several contributors on the most important issues affecting Black people in Canada today. In this excerpt by OmiSoore Dryden, the James R. Johnston Chair in Black Canadian Studies in the faculty of medicine and an associate professor in the department of community health and epidemiology at Dalhousie University, she breaks down the history of how blood donation in Canada has systematically discriminated against Black people and gay men—and why they are interconnected.

The interrogations into the mysteries of the body, including blood, did not occur as objective examinations. Scientific investigations into the body, and its blood, occur within the tapestries of anti-Black racism, colonialism, religiosity, and white supremacist logics. These same logics frame the parameters of citizenship and belonging within Canada and frame the systems of blood donation. As a result, Black people are often associated with having/possessing bad bodily fluids, in particular blood and semen. Through these logics, HIV and AIDS has become a “natural association” with Blackness. As such, Black people and their blood and semen have been a site of contention, containment, and concealment. Although HIV and AIDS impact marginalized populations differently, the criminalization of HIV has negatively impacted Black people. Rinaldo Walcott writes in his book Queer Returns: Essays on Multiculturalism, Diaspora, and Black Studies, “in the age of HIV/AIDS, the Black dick has emerged as an instrument as dangerous as the gun.”(2)

My focus is how the racist (and racist-homophobic) narratives of disease (including HIV and AIDS) inform the “truths” about blood. These racist “truths” are in turn deployed against Black people in Canada. Public blood donation has been the responsibility of two agencies: the Canadian Red Cross Society (from 1940 to 1998) and the Canadian Blood Services/Héma Québec (1998 to the present). Anti-Black racism and “afro-phobia” have impacted public blood donation policies and practices in Canada from its inception in 1940. The Canadian Red Cross Society (CRCS) was an auxiliary to the government’s military medical services in wartime and held its first public, non-military blood donor clinic in 1940 in Toronto. With the slogan “Make a Date with a Wounded Soldier,”(3) Canadians were urged to donate blood, with all donations reserved for use exclusively within the military. In other words, all blood collected was earmarked for military use only.

Dr. Charles R. Drew (1904–1950), an African-American cisgender man, developed procedures for collecting, storing, and transporting large quantities of blood. He began the development of these procedures while studying at McGill University, and these methods and procedures became the basis for national blood collection programs in Canada, the United States, and Britain.(4) “The first blood transfusion recipients were white American and British soldiers, and following the direction of the American Red Cross Society, all blood collected in Canada and the us was racially catalogued with the purpose of ensuring that white soldiers did not receive blood from not-white [people].”(5)

As the creator of the modern blood donation system, Dr. Charles Drew rigorously objected to this practice of the racial segregation of donated blood, arguing that there was no scientific evidence to support such a practice. However, the practice prevailed. Between 1940 and 1942, women, who largely ran the clinics, were not allowed to donate blood, as it was suggested that women would not be able to handle the physical process of donation. Once women were allowed to donate, the practice of racial segregation was applied to their blood. The first peacetime blood donor clinic happened in 1947, with blood now used for non-military use.

These blood narratives of racial segregation and gendered exclusion were understood to fall within the parameters of “safe” blood and thus framed the early practices of blood donation in Canada; they constituted the social determinants, the very conditions, of safe blood and optimal health. Public health discourse has often framed the body as dangerous and problematic, as ever threatening to run out of control, to attract disease, and to pose imminent danger to the rest of society. And in response to this framing, numerous measures have been taken to confine people and to control their environments, movements, and interactions.

HIV, AIDS, and the tainted blood crisis renewed the dominance of science in systems of social control, particularly in dictating appropriate behaviours, thus creating a connection between these behaviours and one’s true nature as a human being. The contamination of the blood supply signalled a significant breach—one in which dangerous bodies (homosexual, Haitian, heroin users, and hemophiliacs—the 4 H) and their blood—infected the general public.

HIV and AIDS marked an important moment in blood donation in Canada. Canada reported its first case of AIDS in March 1982. To keep the blood supply safe, North American health officials placed a ban on men who have sex with men from donating blood. AIDS was considered to be exclusively a gay-related disease. The homophobia embedded in the early detection of AIDS included assumptions of lack of moral correctness and lack of self-control among men who have sex with men. To keep the blood supply safe, men who have sex with men were called on to “take ‘ownership’ of and assume ‘responsibility’ for the virus.”(6)

In March 1983, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States released a list detailing the “dangers” of HIV contamination by naming four vectors for its transmission—homosexuals, heroin addicts, hemophiliacs and Haitians.(7) Blood donor clinic operators were asked to bar these groups of people from donating blood, but also to put them under surveillance. Haitian people, regardless of citizenship, were included in this ban. Concurrently with the political activism of gays and lesbians in the 1970s and 1980s, the political situation in Haiti was catastrophic. In the 1970s Haitian people were fleeing the poverty and repression in a dictator-led Haiti, finding their way to nearby Caribbean countries, the United States, and Canada—specifically Quebec.

Anti-Black racism is not a new phenomenon in Canada or in Quebec, but it is important to note that this influx of Haitian people during this time was met with xenophobic fears. As newcomers to Canada, Haitians faced challenges including racially motivated violence, racial harassment, and racial discrimination. It is not surprising, then, that when HIV/AIDS began to be diagnosed within Haitian communities, the desire to find the origin of HIV/AIDS shifted to include Haitian people. As a result, not only was Haiti framed as a place riddled with HIV and AIDS, but also all Haitian people were considered to be carriers of this deadly disease. Stereotypes and fiction were presented as medical and scientific objective study. Haitian people were described as “mysterious, isolated, disease-ridden, blood-maddened and engaging in exotic, violent voodoo rituals.”(8) These racist stereotypes existed long before the advent of AIDS and the “scientific” blaming of Haitian people in North America and in Haiti.

Not only did the CDC release a list detailing the 4 H club in March 1983, but the Red Cross also issued a pamphlet asking per- sons at “high risk” of getting HIV/AIDS (in this case gay and Haitian people) to refrain from donating blood.(9) Predictably, these actions were met with outrage and protest. On April 20, 1990, about 80,000 Haitian people marched across the Brooklyn Bridge in protest of the decision by the United States Food and Drug Administration to outright ban Haitian people from donating blood. Photos from the protest show New York streets overflowing with protestors holding signs ranging from “Proud of our Blood” or “International Criminals like FDA Scientists Belong in Prison. They Try to Kill African Race” to “Find a Cure for AIDS.”(10) Overall, 150,000 Haitian people protested the ban on Haitian people from donating blood.(11) This action tied up traffic for hours while simultaneously shutting down Wall Street trading.(12) The ban was overturned later that month. Racism and homophobia led public health officials to believe that simply by banning Haitian people and men who have sex with men from donating blood, the blood supply would remain untainted. And it was within this climate that the tainted blood scandal was framed—the inability to bar the vectors of disease: the 4 H club.

From the mid-1980s to the 1990s, blood donation recipients became infected with HIV and hepatitis C through tainted blood products. This was a public health disaster, an outcome of inadequate screening procedures and a new and (at the time) undetectable sexually transmitted infection. The panic regarding HIV/AIDS is conflated with the panic regarding homosexuality and the continuing colonial panic about miscegenation. As has been stated elsewhere, HIV and AIDS is an epidemic on multiple simultaneous levels: it is an epidemic of a transmissible lethal disease as well as an epidemic of meanings or significations.(13)

Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada is out now with the University of Regina Press.

Walcott, Queer Returns, 206.

André Picard, The Gift of Death: Confronting Canada’s Tainted-Blood Trag- edy (Toronto: Harper Collins, 1995).

Charles W. Carey, Jr., African Americans in Science: An Encyclopedia of Peo- ple and Progress (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2008).

OmiSoore H. Dryden, “‘A Queer Too Far’: Blackness, ‘Gay Blood,’ and Transgressive Possibilities,” in Disrupting Queer Inclusion: Canadian Homonationalisms and the Politics of Belonging, OmiSoore H. Dryden and Suzanne Lenon, eds. (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2015) 116–32.

Georges E. Fouron, “Race, Blood, Disease and Citizenship: The Making of the Haitian-Americans and the Haitian Immigrants into ‘the Others’ during the 1980s-1990s aids Crisis,” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 20, no. 6 (2013), 707.

Régine Michelle Jean-Charles, “The Sway of Stigma,” 64.

Paul Farmer, AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 3.

Commission of Inquiry on the Blood System in Canada, 1997, xxiv.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra