As he hunkers down in Lebanon, biding time before he and partner Aamer get the official okay to come to Canada, Syrian-born Danny Ramadan jokingly blames his “unholy union” for the war’s arrival in Damascus.

He can find levity in recalling the backgammon and card games he and Aamer used to play in the safety of a bathroom as sniper and rocket fire ruled the Syrian capital’s streets.

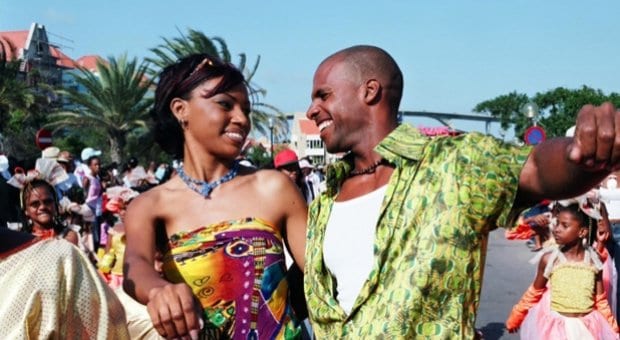

Ramadan’s gallows humour reminds me of home — and my fellow Trinidadians’ ability to tease the ridiculous out of a crisis. At the height of a coup attempt in July 1990, Trinidadians who found themselves stuck at friends’ or relatives’ homes threw spontaneous curfew parties to relieve boredom, to forget that their proudly cultivated, carefree approach to life could actually be under threat, or just to prove that armed insurrection was no match for the Trini love of a good fete.

One anecdote from that period — probably steeped in typical hyperbole by the time it was told for the umpteenth time — was that a police officer, drawn to the uproar of coup festivities at one home, was asked if he could make a run for ice — “please” — to keep the beer and other libations at optimal temperature for consumption.

Partying is serious business. Perpetual Pride, Trinidad-style.

This year I’ll be forsaking Vancouver Pride to head home for my 30th high-school reunion to soak up some of that devil-may-care vibe that I left behind almost 11 years ago when I decided to make Canada my new home. Unlike Ramadan, I didn’t flee a war-torn country with anywhere near the level of deeply rooted familial and cultural strictures on what is “acceptable,” “normal” or “right.” As I wrote in my first-ever column for Xtra, Trinidad is no utopia, but I do not fear for my life as a gay person.

Yet the parallels are there.

The percentage of gay people who end up in traditional marriages in Syria is high, Ramadan observes. Anecdotally, at the very least, many Trinidadians do the same to keep up appearances. Trinidadians may be partial to a good fete, but they like their sexual relationships to appear straight, if not monogamously narrow.

As Ramadan succinctly puts it, “it’s something you are trained to do.”

In Syria, anyone caught having gay sex faces up to three years in prison and is subject to public shaming through the publication of their photos and warnings for people, especially children, to avoid them.

For many Trinidadians in 2013, the fear of ridicule, or diminished reputation, is still enough of a deterrent to being unabashedly out, never mind the colonial-era laws that still may, on a whim or a whiff of blackmail opportunity, be invoked to punish the deviant and different.

In August last year, there was a fleeting spark of political leadership when the prime minister reportedly promised to “put an end to all discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation.” That lasted only until the island’s Inter-Religious Organization reminded politicians that “the Constitution is based on the supremacy of God.”

What differed from politics-as-usual was the public response: at least some people called bullshit on the politicians’ “cop-out” and wondered about the absence of “real consultations” on the issue with a broader spectrum of the electorate. Since I left Trinidad, such progressive reactions to homophobia are no longer few and far between.

The worst I can expect when my marital status and sexuality come up once I hit home shores — and they will — are one or two bemused expressions, most likely silence, maybe a change of subject along the lines of, “I see … so … you’re enjoying Vancouver?”

Plus, the requisite gossip once I’m out of earshot.

Thirty years after leaving high school, that’s a walk in the park and a piece of cake.

Natasha Barsotti is the staff reporter at Xtra Vancouver.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra