To me, androgyny is the highest form of beauty. One of my favourite experiences is when I’m walking behind someone and say to myself, “Ooh, I like his clothes, I like his hair; I bet he’s really hot.” The person turns around and I realize she is a very masculine-presenting or dykey woman. Likewise, the more gloriously, swishily, unapologetically feminine a gay guy is, the more attractive I find him. The gender dichotomy is boring, way too 20th century, and so many cultures have long spoken of the third sex: the blending and deconstruction of gender is part of many mythologies.

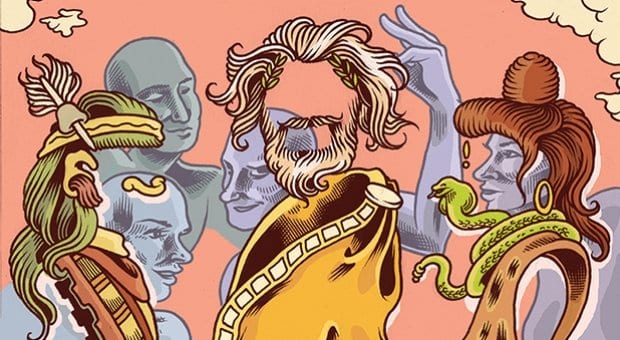

The Greeks are an unfailingly dirty place to start. Among many stories of lust- and sex-filled genderbending, the origin of Teiresias, a mythological blind oracle, is especially delightful. His story begins with his finding a pair of copulating snakes and striking them with a stick. Angered at the treatment of her minions, the vengeful goddess Hera transforms Teiresias into a woman. As a woman, Teiresias marries and has children, but several years later he once again strikes copulating snakes, and Hera transforms him back to his masculine form. Though different stories have different explanations for how he was blinded, one version has Hera and her husband, Zeus, debating whether men or women derive more pleasure from sex. When they ask Teiresias, an expert on the subject, “he said that if the pleasures of love be reckoned at 10, men enjoy one and women nine,” reinforcing Zeus’s opinion. The ever-vindictive Hera blinds him for siding with her virile husband, and Zeus, feeling bad, offers Teiresias the power of prophecy.

The pervy antics of Greek gods seem juvenile compared to the primeval deity Ishtar, an incestuous goddess worshipped by several ancient Semitic kingdoms of Mesopotamia, somewhere around 2000 BCE. She was something of a schizophrenic mother goddess, reigning over life and death as the many-breasted Opener of the Womb and the Destroyer Queen of the Underworld, respectively. Ishtar was also worshipped in the kingdom of Assyria as the divinity of war. She carried a quiver and bow and was depicted with a beard as a manifestation of her warmongering nature. Ishtar straddled the social boundaries of man and woman, demonstrated by her devotees, who were usually men who either presented characteristics of both genders or appeared fully feminine.

With roots in Vedic mythology and originating in the Classical Sanskrit period, beginning around 1200 BCE, various Hindu gods, including Lord Shiva, transcended gender in different ways. Shiva is often mistakenly attributed as the evil destroyer god, though his actual role is dissolving and recreating the universe when the balance between good and evil is disturbed. A number of major symbols are commonly associated with Shiva: his unclad body covered in ashes represents transcendental manifestation unaffected by the physical aspect of the universe. Lord Shiva’s kundalas, a pair of earrings, are called alakshya, “which cannot be shown by any sign,” and niranjan, “which cannot be seen by mortal eyes.” The kundala in his left ear is the type used by women, the one in the right by men, and so in some beliefs they also represent the embodiment of Shiva’s feminine energy, shakti.

Similar to the mother goddess Ishtar, though a world away, Mesoamerican peoples had Tlazolteotl, the Goddess of Filth. The Aztec and Huastec peoples of pre-Columbian Mexico likely worshipped a similar deity for centuries, though when the former conquered the latter in the mid-15th century, their beliefs merged. Tlazolteotl’s two-part name is derived from the Nahuatl tlazolli, which describes filth, garbage and human waste, and teotl, a generic, genderless word signifying a deity. Although she is almost always thought of as feminine, in some incarnations she is seen as a warrior woman with both masculine and feminine traits. Tlazolteotl was believed to be the goddess who inspired, and also forgave, sexual transgressions. Among numerous roles for different worshippers she oversaw childbirth, death, rot, menstruation and confession — the act of eating the filthy sins of her worshippers.

Today, especially in Western society, we demand that our gods be tame, well behaved and simple. Gods of the old world were often shifting, contradictory, unknowable: dark, primal things, glorious and horrible, much like the humans who worshipped them. Cyclical life and death, the duality of creation and destruction, woman and man, are recurring themes in many mythologies. Androgyny was part and parcel of the dualities of the divine.

Whether we like to admit it or not, we all have within us a mixture of masculinity and femininity. For me, being queer is a means of embracing that, toying with and destroying gender. In this sense, especially in Toronto, the divine often walk among us.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra