Ah, the freedom of conscience.

There it is, the number-one freedom in the Canadian charter: the right to move through this country in ways that don’t compromise your values or beliefs. This freedom underlies other significant parts of the charter, namely the right to bodily autonomy and equality, or sections seven and 15, respectively.

Who would want to live in a place where we couldn’t make personal decisions about our own bodies, decisions that our own consciences support? Say you want to abort an embryo or fetus growing inside you—that’s your right. Or say you have a terminal illness or awful quality of life, and you want to die on your own terms. That’s your right, too.

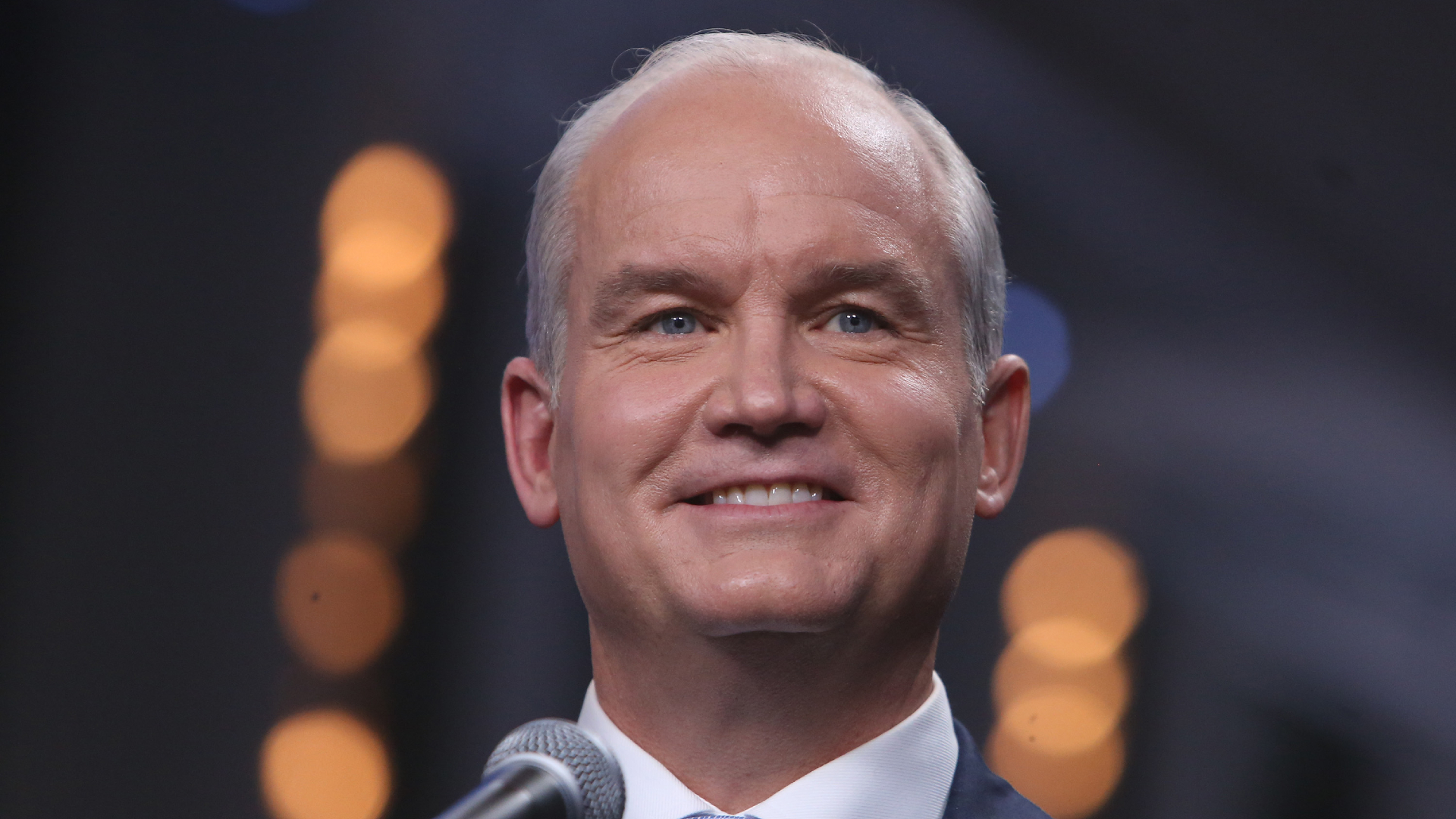

Except, in Conservative leader Erin O’Toole’s vision, in these scenarios it’s the doctors exercising their consciences, not the patients. In fact, a patient’s conscience never even enters the conversation. This is contrary to the spirit of our Charter rights and a slap in the face of anyone who believes in the principle of bodily autonomy and the adage “my body my choice.”

O’Toole has made it abundantly clear he identifies as pro-choice. But this man who wants to lead Canada is also a rigorous defender of health care professionals’ conscience rights—rights that will almost exclusively be used to deny abortions, medically assisted dying and support for trans patients.

He also supports free votes, which are essentially conscience rights for MPs. It’s an odd concept, considering MPs are supposed to vote in their constituents’ interests and not their own, and a conscience is a very personal thing. But there it is, in the 2021 Conservative policy declaration: all votes should be free, save for a few non-negotiables (“budget, main estimates and core government initiatives”).

First, a little history: free votes have long been used by parties in countries with parliamentary systems. Theoretically, it’s the antonym of party discipline; members’ votes won’t be whipped to get behind the leader’s or party’s position. Practically, though, there’s usually still a little lobbying and vote-whipping behind the scenes, either from the top down or among party factions. There’s no definitive record of when it was first used in Canada, but the 1946 vote on continuing wartime milk subsidies has been described as an early instance. The next free vote of note came when deciding Canada’s new flag in 1964.

It was in the post-Quiet Revolution era when free voting took on a more conscientious identity. An Ottawa Citizen piece suggests that was the handiwork of Liberal strategist Allan J. MacEachen, for use in a vote about whether to abolish the death penalty. By allowing a House-wide free vote, the public couldn’t blame any one party for the outcome. The free vote also allowed the prime minister (then Pierre Elliot Trudeau) and members of his cabinet to decline meetings with religious leaders, since ostensibly he wouldn’t be influencing anyone. The vote came to 131-124, and capital punishment was abolished.

“By making these issues of conscience, they don’t have to make these issues of confidence.”

Last year, before an election was even a blip on the horizon, I spoke with Christopher Raymond, a lecturer in politics at Ireland’s Queen’s University Belfast and a researcher on free voting in Canada, among other things. He explained that parties—particularly those forming the government at any given time—will typically trigger free voting on conscience issues to insulate themselves from loss of power. “If [for example] the party allows for a vote on abortion to take place, but they don’t have the votes, it won’t bring down the government and force an early election,” Raymond told me. “By making these issues of conscience, they don’t have to make these issues of confidence.”

Federally speaking, free voting is most often used on private members’ bills and on questions of “morality”: banning discrimination based on sexual orientation (1996); same-sex marriage (2006); abortion and aspects thereof (1969, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 2008, 2012, 2016, 2021 and probably some others); medical aid in dying (2016, 2020) and banning conversion therapy (2021).

The intention of free voting is to give MPs the permission to stray from the party line on a certain issue and to vote in the interests of their constituents. However, as a post-mortem analysis published at the University of Regina on the 1988 abortion vote remarked: “MP voting on this issue did not appear to be influenced by the preferences of constituents, but was significantly influenced by the personal ideologies of the MPs themselves. Under an agency theory view, these results can be interpreted as evidence of ‘shirking’ behaviour by legislators.” (Shirking is when an elected representative disregards and votes against the position of their constituency.)

In a country where abortion, same-sex marriage and medically assisted dying are legal and supported by a majority of Canadians, free votes are often seen as a victory by Conservative hardliners and right-wing organizations with a stake in government—and there is a very good reason for that.

“In a battle of whose conscience rights matter most, marginalized Canadians are the ones who stand to lose.”

By allowing free votes on issues of “conscience,” O’Toole is empowering, and abdicating public accountability for, the members of his party he knows would vote for things like restricting abortion and medically assisted dying. He gets to call himself progressive and pro-choice personally while washing his hands of the opinions of his fringiest members. In return, those hardliners and their agendas gain more legitimacy with an increasingly polarized public.

Simultaneously, this strategy lets O’Toole court voters (and candidates and donors) who disapprove of the very things for which O’Toole supposedly stands. This isn’t a hypothetical scenario: just a few months ago, a prominent anti-choice organization congratulated O’Toole for “allowing free votes on issues of moral conscience, such as abortion,” noting his “commitment […] to pro-lifers” on the mercifully defeated sex-selective abortion bill—itself an attempt to erode abortion rights in the same vein as the “death by 1,000 cuts” strategy employed in the U.S. (See: Texas.) He says there is no contradiction in his stance, but let’s be real: a man selling himself as pro-choice while committing himself to pro-lifers is political contortionism at its most deceptive.

Still, for O’Toole, this appears to be a win-win-win situation. He gets to pander broadly, promising everything and nothing at the same time. Meanwhile, in a battle of whose conscience rights matter most, women and other marginalized Canadians are the ones who stand to lose. Enabling wider powers on conscience rights, whether legislatively or by creating a political vacuum, will have real-world consequences for people’s health and quality of life. But even O’Toole’s casual backpedal on Aug. 20, in which he promised an effective referral process in which objecting doctors would have to refer a patient to another professional—which does not currently exist in most of Canada—reeks of opportunism.

But I guess that’s politics, right?

As my conversation with Raymond went on, I asked him what he made of O’Toole beating his chest over doctors’ conscience rights. “I see a lot of that as a nod to the fact that, despite the considerable secularization of the last 50 years, the Conservatives still are very dependent on religious voters,” he said. “So, it is a strategic positioning on the issue, where it tries to placate both sides within the party and also in the wider electorate.”

“Right,” I said. “So trying to play both sides kind of leaves everyone dissatisfied.”

“That’s usually the outcome of trying to keep multiple groups of people who are diametrically opposed happy,” he replied.

When push comes to shove, there is no way O’Toole will be able to satisfy both the hardliners and the more progressive contingent of Conservative supporters. If he is given any power in the next election—and right now it’s looking likely—he will eventually have to choose between them. As of yet, we have no reason to believe he will choose the side of genuine social progress.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra