The only thing worse than an ’80s revival is listening to 20-somethings on TV reminisce like they were actually there.

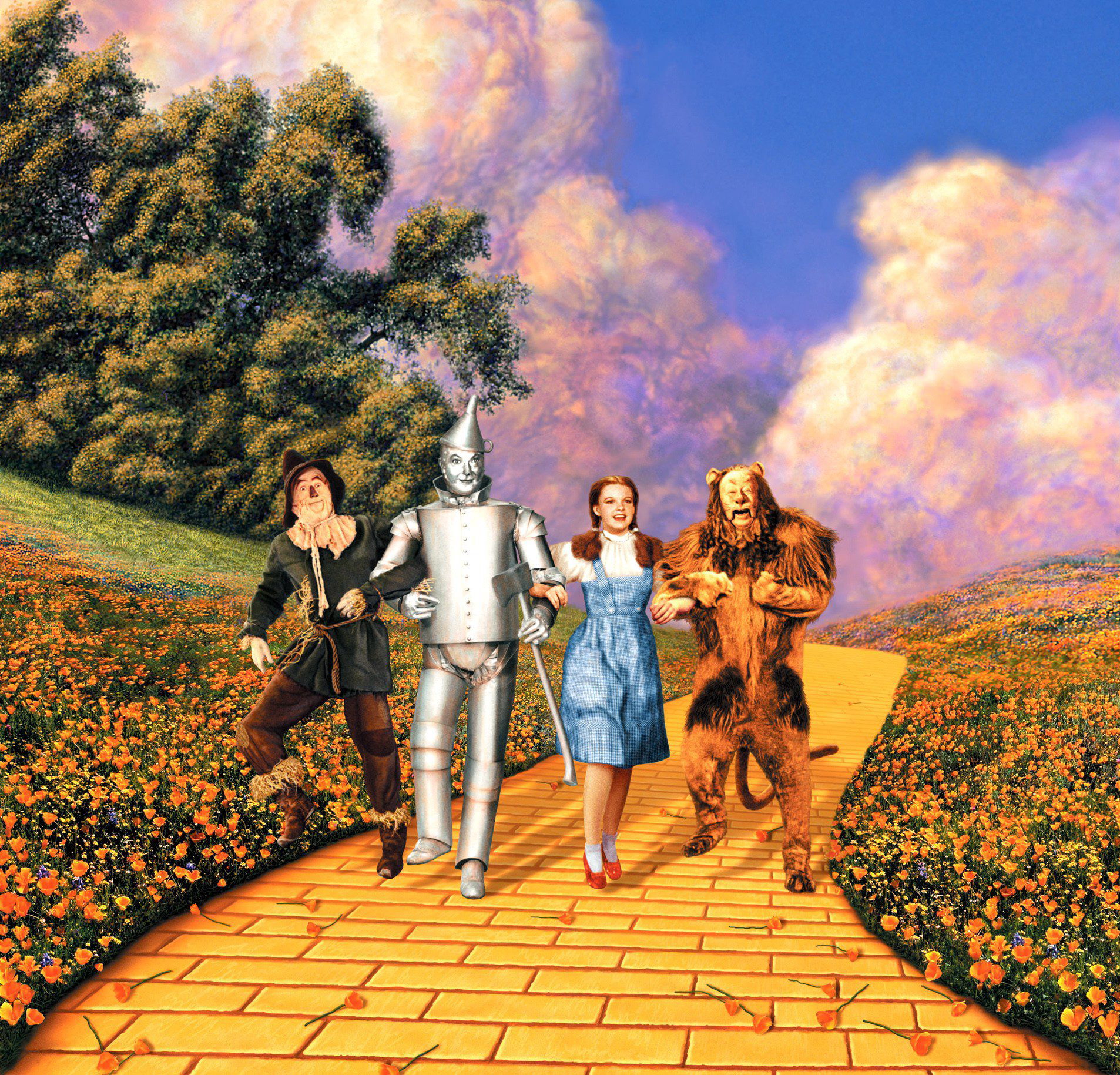

My fondest memories of that decade were not the clothes or the music, but playing the Scarecrow in my high school’s production of The Wizard of Oz. That was my Breakfast Club.

My biggest competition for the part was Brad Callaghan. We had been each other’s safety nets since kindergarten. When we were seven, my grey-haired immigrant mother kicked Brad out of our house for showing me his bum. I was under lock and key for years.

“Don’t talk to me,” Brad said when I got the part. He avoided me in the halls and skipped the classes we had together. I felt personally responsible when he dropped out completely.

My new best friend, Gord, was cast as the Tin Man. Gord and I had bonded the year before, working together on the school paper. Up to then, he didn’t know I spoke English, scared as I was to open my mouth for fear of being labelled a fag.

Gord wasn’t the first black friend I ever had, but he was certainly the tallest. As if he didn’t attract enough attention, he walked around school wearing a name tag that read “Token black.”

When Gord and I weren’t rehearsing for the play, we were on the phone discussing it. We spent hours imitating Glinda the Good Witch who could not say “almost always” with any irony.

“She keeps putting the em-pha-sis on the wrong the syl-a-ble,” Gord said, as I rolled on the floor laughing.

“What’s that sound?” he asked.

“Ave Maria,” I said.

“What? Do you live in a cathedral?”

“Sorta.”

There were enough crucifixes and Madonnas in our house to give a Vatican gift shop a run for its money. Everywhere you looked it was halos and stigmata. The phone was directly beneath the grandfather clock that chimed Ave Maria every 15 minutes.

“I have a secret,” Gord whispered.

“I do too.”

“I think we have the same secret.”

“You tell me yours and I’ll tell you mine.”

Gord took a deep breath and said, “I think I’m kind of gay.”

All I had to do was say “I am too,” but suddenly it was like the eyes of every saint and martyr in the house were upon me.

“Nope! Not the same secret!” I said, and hung up.

I turned around and there was my mother dressed in black for a memorial service. Mom was a recreational mourner and often mistaken for a widow. It was like she had been watching me through a crystal ball, appearing from a black mist. She stood there raven-like, interrogating me with her eyes.

The phone rang. I jumped so high I nearly bumped the Ave Maria clock with my head. “Hello?” I said nonchalantly, praying my mother couldn’t hear Gord’s tirade. “Sorry,” I said, “wrong number.” Click.

I did what every teen in the ’80s did in times of crisis; I ran to the mall. Brad was there working at the House of Knives kiosk. It was the first time I had seen him since he quit school. He was wearing eyeliner and makeup, his hair styled like Tom Bailey of The Thompson Twins.

“How’s Oz?” he asked.

“Miserable.”

“Good.”

“Not funny. I think I just really pissed off Gord.”

“How?”

“It’s a secret.”

“You can tell me. We go back.”

I looked over both shoulders and whispered, “He thinks he’s gay.”

“Really?” Brad said, surprised.

“And he thinks I am too!”

“Are you?”

“No!” I said, a little too quickly.

“Right.”

I looked away and sighed.

“It’s okay,” Brad said. “Why do you think I quit school?”

“Because you didn’t get a part in the play?”

“Can we talk?” he said, imitating Joan Rivers. “I was sick of getting beat up!”

“When did you get beat up?”

“You obviously don’t get to the smoking area very often.” Brad picked up the phone and started punching in numbers. “Gord? It’s Brad. Meet me and Tony at McDonald’s in 15 minutes.” Brad started counting the cash and locking up. “Ready?” he asked.

“Aren’t you afraid you’ll get fired?”

“It’s the House of fucking Knives, for Christ sake!”

Gord ran towards Brad’s blue Mustang as we pulled into the parking lot of McDonald’s.

“I shouldn’t even be speaking to you,” Gord said, getting into the car.

“Chill out,” said Brad. “Tony has something to tell you.”

“I think I’m gay,” I said.

“I am too,” said Brad.

Gord eyed us suspiciously. “And how did you two come to this conclusion?” he asked.

“I told Brad your secret.”

“Use me for a guinea pig why don’t you? It’s because I’m black, isn’t it?”

“I’m sorry. I panicked!” I said.

“This was not the conversation I had prepared myself for,” said Gord, crossing his arms in front of him.

“So now what?” I asked.

“Now,” Brad said with a hint of vengeance, “we go to a gay bar.” The car took off. Gord and I were thrown back into our seats, the blue Mustang sputtering wet farts of exhaust. “It’s My Life” blared, as the CN Tower loomed larger and larger on the horizon.

Brad took us to The 101 on Jarvis St. We walked past a suit of armour into the black-lit bar. Everything about me glowed —my clothes, my teeth, the whites of my eyes–it was like being in that movie Tron.

“So what do you think?” Brad asked.

“I can’t believe I’m in a gay bar! “

“This is nothing. Wait till I take you to a bathhouse.”

My mother was knitting on my bed when I got home. She grabbed my shirtsleeve and sniffed it. “You’ve been smoking,” she said in Portuguese. “I can smell it.” I braced myself for the third degree. “If your father knew you were out this late he’d kill you,” she said.

Mom was always projecting her anger on my father. She was the proverbial man behind the curtain. This time it was different. The self-loathing she usually inspired wasn’t there. I felt neither guilty nor the need to apologize.

Glinda would never master “almost always,” and Dorothy couldn’t sing but that wouldn’t prevent The Wizard of Oz from selling out its entire run. The sets looked like they came from an MGM soundstage, we had a Tina Turner–inspired Wicked Witch and, modesty aside, I made a pretty convincing Scarecrow.

“I kept expecting straw to come out of your mouth,” Gord said.

Despite a mention in the local paper, my parents never went to see my performance. Dad was probably clueless; Mom was boycotting. As far as she was concerned, at best I was smoking, at worst looking at boys’ bums. Either way, she held the play responsible.

When the lights came up on the final performance I saw my sister in the third row giving me a standing ovation. It was like a scene out of one of those manipulative feel-good movies where the ingénue returns in time to watch the hero redeem himself.

That moment would become ingrained in both our memories as a defining one. From then on I would forever in her mind be the Scarecrow from The Wizard of Oz and she would be my Glinda, the one person in my family I knew was cheering for me.

On a clear day you could see the CN Tower from my high school. It always reminded me of Brad. “I can think of 101 places I’d rather be,” he wrote in my yearbook. He wasn’t kidding. By semester’s end he would be living downtown, working as a waiter. Between the two of us we have lived in seven different cities, in three countries, on two continents, and yet have managed to remain in touch.

“Thirty-five years we’ve known each other!” he said at Christmas. “Can you fucking believe it?”

“Yes I can,” I told him. “You set me free.”

For years my sister sent me Wizard of Oz memorabilia for birthdays and Christmases until I told her what a friend of Dorothy was. The play long forgotten, I just assumed she was referring to my sexuality.

“Why does everything have to be gay with you?” she asked, sounding like she was the butt of an elaborate joke, effectively ruining what was meant as a Hallmark moment.

If I only had a brain I would have told her it was her conjuring those memories that made her gifts so special and that her ovation that night was not just for my performance but also for finding the courage to be me.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra