William Walker (left) and his husband, Eric Iles, dressed up for a Pride celebration in 1973. Credit: Courtesy of William Walker

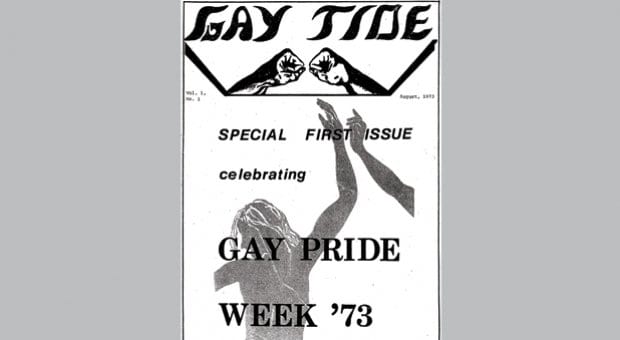

The first issue of Gay Tide, published by GATE, celebrates Gay Pride Week ’73, which drew about 100 people. Credit: Xtra files

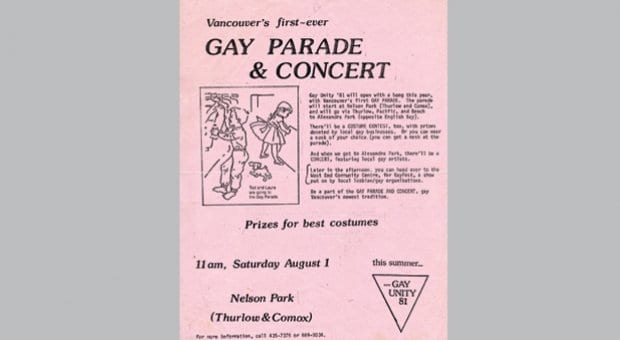

A flyer advertises Vancouver’s first gay pride parade on Aug 1, 1981. About 1,500 people marched from Nelson Park south along Thurlow Street to Alexandra Park. Credit: David Myers

By 1983, attendance at Vancouver’s Pride parade had grown to 2,000 people. Credit: David Myers

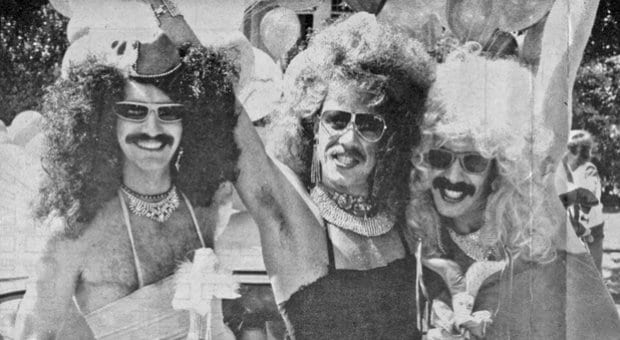

The French Maids won the Most Outrageous Costume award in 1985. Turnout hit an estimated 2,500. Credit: Daniel Collins

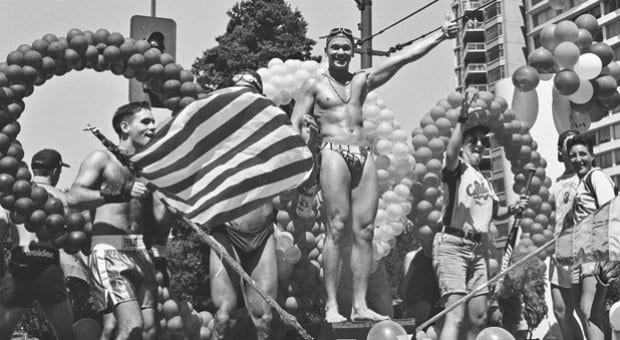

Hosting the 1990 Gay Games marked a turning point for Vancouver’s gay community, as people came pouring out of the closet. Attendance jumped to 8,000 at that summer’s Pride parade. Credit: John Kozachenko

Attendance at the 1993 Pride parade jumped to 15,000. Credit: John Kozachenko

Rain can’t deter parade-goers in 1996. Estimates swing wildly between 25,000 to 50,000 attendees. Either way, it marked a significant jump in turnout. Credit: John Kozachenko

An estimated 100,000 people attended the 1997 Pride parade. Organizers say that number tripled in 2006 and topped 600,000 in 2012. Credit: John Kozachenko

Terry Wallace Credit: Curtis Lord

This 1997 photo shows some of the key early organizers of Pride. Clockwise from top left: Garry Penny, Peter Kinlock, Terry Wallace, Karen Bitz and Malcolm Crane’s partner, Stan Weese. Credit: Tom Bowen

Garry Penny Credit: Andrea Kucherawy

William Walker has seen 42 years of Pride celebrations. Drawn to the thrill of the city, he swept into Vancouver as a young sailor in 1969 and never left.

Today, he bustles around his Yaletown apartment, dodging fantastical dyed feather hats, reams of French lace and restored 19th-century silk dresses.

To Walker, the last 40 years have whirled by in a joyous celebration of gay. Here is the sweeping blue 18th-century-style dress he wore to celebrate Pride — was it ’87 or ’77? There, in a photo, his husband, who died of cancer, wears a crisp military uniform that Walker sewed himself.

Walker was called a fag at marches in the early 1970s, attended covert gay picnics in the late ’70s, marched in the first Pride parade in the ’80s, waved to a new generation in the ’90s from a perch at the Denman Street Milestones restaurant, and is still sewing gossamer wings for faeries this year, as the parade gains official civic status as a Vancouver festival.

The Vancouver Pride Society (VPS) makes the arguable claim that this year marks the 35th anniversary of Pride (see “Is Vancouver Pride really 35 this year?” on dailyxtra.com). In fact, 1979 — the parade’s supposed birth year by the VPS’s count — was not a particularly significant year for Pride at all. Walker’s whirlwind of memories proves the history of Pride is much more complicated. There are any number of years in which Pride could have started.

Perhaps Vancouver Pride started like a joke: two gay radical leftists walk into a bar.

It was a quiet, rainy night in January 1971. George Smith taught education at Simon Fraser University, and Gordon Hardy was his former student. Over beer, talk came around to the Vancouver gay scene. Two years had passed since the riots at Stonewall, but the same revolutionary spirit had yet to catch in Canada.

“There was no ‘gay community’ back then,” Hardy remembers. “There was just the ‘gay scene.’”

Gay life either unfolded in bars and underground parties — drinking from paper bags and listening for police sirens — or stealthily in the ferns by Lees Trail. There were no gay community centres, no parades and no advocacy groups.

Hardy and Smith decided that night to start a gay discussion group. It was a success. Within a few months, the group blossomed into the Gay Liberation Front. A few months later, the Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE) followed on scene.

That August, the GLF and GATE rallied on the steps of the Vancouver courthouse to support gay activists marching simultaneously in Ottawa. Ottawa poured with rain, but in Vancouver the sun shone. A small crowd of 20 people assembled around the old Vancouver courthouse to hear about “the ghetto of the mind and of the soul” and the “psychiatric oppression of gay people.”

The protests of 1971 were followed by celebrations of Gay Pride Week in 1972 and ’73.

Gay Vancouver had taken to the streets, in protest and in celebration, for the very first time.

Perhaps, as the VPS suggests, Pride began in the late 1970s. For Gay Unity Week in 1979, 700 gays and lesbians drive out to Mission to play volleyball and run three-legged races in a farmer’s field.

While the celebrations of the 1970s were understated, transformation bubbled beneath the surface. The dramatic 1972 city council elections tossed out the conservative Non Partisan Association and instead elected a slate of young progressives. Among them was a freshman alderman named Mike Harcourt, who would eventually become mayor of Vancouver, premier of British Columbia, and one of the most important allies the gay community of British Columbia has ever had.

The new attitude in city council seeped into the police force, gradually thawing tensions between the gay community and the Vancouver Police Department.

Though Vancouver gay bars and clubs saw their share of police attention in the 1970s, one writer in the gay newsletter Search News noted the contrast between here and Toronto:

“Toronto is in a siege mentality. With the smear tactics of the Jaques case . . . the raid on the Barracks . . . people are divided and afraid . . . Here in Vancouver, perhaps, we have been more fortunate.”

By the late 1970s, city council had fallen back into the hands of the Non Partisan Association, but new attitudes were already incubating.

The summer of 1981 may hold the strongest claim to the origin of Pride in Vancouver.

The previous year, city council had rejected a bid to officially declare Gay Unity Week. Vancouver mayor Jack Volrich politically wrote, “It is the long-standing policy of the Mayor’s Office to not approve proclamations for events . . . which may draw public controversy.”

Two conservative aldermen, Bernice Gerard and Doug Little, led a crusade against the parade in which clergymen were invited to the city council chamber to declare their moral revulsion for gay people. The mayor had to silence one before a graphic description of anal sex became more than the council chamber could bear.

But in 1981, everything abruptly changed. After nine years as an alderman, Mike Harcourt was elected mayor of Vancouver. Harcourt had been speaking at gay rallies and dancing at gay balls for years and won with the firm support of the gay community.

“He saw us as his electoral base, which is how a politician should look at it,” remembers Jim Deva, co-owner of Little Sister’s Bookstore. “He had absolutely no homophobia at all.”

Harcourt himself remembers it in more absolute terms: “It was a matter of human rights and people feeling valued and included in the Vancouver community,” he tells Xtra.

On a sunny Aug 1, 1981, about 1,500 people marched in the first Pride parade from Nelson Park down to Pacific Street and along to a rally at English Bay. There, standing atop a gazebo platform, Harcourt’s personal secretary, Jane MacDonald, quavered, “I am hereby honoured to proclaim the week of Aug 1 to 7, 1981, as Gay Unity Week!”

The parade flowed without a hitch. Marchers in drag, leather and ordinary clothes walked down the street under police escort. Not one arrest was made (“Take note, Toronto!” one writer snarked). Even an elderly lady shouting “Delinquents!” out of her car window was met with jovial enthusiasm.

The Pride parade, as we know it now, had started.

Pride was not quite like it is today, however, until the year everything fell apart.

In 1993, Malcolm Crane, then-president of the Pride Community Foundation, the de facto dictator of Pride, suddenly and unexpectedly died. Crane had grasped management so closely that nobody realized he had been quietly funding the parade with his own money.

With 10 weeks to go, the foundation was dead broke.

“I guess we’re not going to have a parade,” board member Rob Atkinson said to the board of the foundation, one grim Saturday after Crane’s death.

“Over my dead body we won’t,” Garry Penny replied.

Penny and his best friend, Terry Wallace, were bar owners. Penny ran the Denman Station, while Wallace managed the Castle Pub. They agreed to front the money for the parade.

In less than three months, Penny, Wallace and Atkinson took the reins and pulled the parade together.

“We did the unheard of. We actually made money that parade,” Atkinson remembers.

They took in $20,400 and spent $19,800. The remaining $600 went to incorporate the Vancouver Pride Society, which runs Pride to this day.

Perhaps future gay historians will someday look back at 2013, the year the Pride parade was officially designated a civic event, and say that this is the year Pride really started.

Regardless, there are only a few people left who remember all the way back to the beginning.

“Most of my old friends are gone,” Walker says, flipping through his photo album. “Old age. Drinking. HIV and AIDS. Life catches up with you. I’m lucky I’m still here.”

When a new generation marches this year, Walker will once again be there to watch.

The founders of Vancouver Pride

Terry Wallace

Terry Wallace, manager of the old Castle Pub, was a backbone of the Pride parade through the 1980s and ’90s. He used the Castle, the busiest afternoon pub in the gay community, to run 50/50 draws and pull-tab machines, raising enough money to keep the parade alive through its toughest years.

More importantly, Wallace is remembered as the soft-spoken peacekeeper of the Pride Community Foundation.

“Terry was amazing,” Jim Deva remembers. “He was the dude who said, ‘Calm down, you come over here, you go over there, let’s settle this.’ He was a very wise and beautiful man. Very humble. He just worked in the background.”

Wallace’s role as a warm father figure earned him the nickname “Papa” among his friends and colleagues.

“He was my best friend,” says Garry Penny, who worked with Wallace on Pride. “He meant everything to me.”

Wallace died in 2004 and is commemorated at Pride by the annual Terry Wallace Memorial Breakfast.

Malcolm Crane

Malcolm Crane was the most powerful, influential and divisive figure in the history of Vancouver Pride. From February 1984, when he was elected chair of the newly formed Pride Festival Association, to 1993 when he suddenly died, Crane was the king of the parade.

In 1987, Jim Deva and Edmund Robichaud tried to quietly switch leadership, to give Deva a turn at the wheel. Without saying a word, Crane appointed new board members and had himself promptly reelected chair.

While Crane made enemies, and is often remembered as a dictatorial villain in histories of Pride, the same stubborn pragmatism also helped the parade carve out a place for itself in Vancouver politics.

“A lot of people criticize Malcolm Crane, but his father had been a city councillor and he knew how politics worked,” Jim Deva says.

Deva remembers Crane facing down local politicians and police chiefs, threatening in his characteristic baritone growl to bring down angry demonstrations on their heads if they would not protect gay citizens.

“He knew how to deal with them,” Deva says.

It was in memory of Crane that the first item added to the constitution of the new Vancouver Pride Society, after his death, was a term limit for executives.

Garry Penny

Garry Penny, a bar owner from Toronto, arrived in Vancouver in 1979 to run the Denman Station, a tiny basement gay bar in the West End. He brought an unequalled wealth of experience and business acumen to the Pride Festival Association — Penny was already a gay activist 10 years before our prime minister was born.

When Malcolm Crane died in 1993, Penny graciously stepped aside to allow a new generation of leaders to take over but continued to run picnic fundraisers for the parade and keep a watchful eye on the society. It was Penny, along with Terry Wallace, who blew the whistle on financial problems in the VPS in 2003.

“I think it’s important the parade keeps going,” Penny says. “I’ve seen it all. And the ’50s and ’60s, those were bad, bad times for gay people. And we can never let ourselves go back there. We have to show ourselves all the time.”

Penny is 83 years old and lives in retirement in Victoria.

This piece is much indebted to the historical work of Robert Rothon, Ron Dutton, David Myers and Kevin Dale McKeown.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra