Newcomers to Vancouver’s West End often curse the traffic circles and multiple street blockages, believing them to be misguided traffic-calming measures.

It’s not why they’re there.

They were put in to stop johns trolling for hookers.

They’re artifacts of the mid-1980s when the city began pushing the prostitutes — straight, trannie and gay — out of the safety of the West End, forcing them onto the dangerous strolls of Richards St and the then-bleak warehouse district now known as chic Yaletown.

They were heady times for Vancouver. Mayor (later premier) Mike Harcourt’s NDP-friendly regime had to deal with Social Credit Premier Bill Bennett’s right-of-centre government in Victoria. And the city was getting ready to host the world for Expo 86.

Change Expo to Olympics and not much has changed.

It was the beginning of the gentrification of the West End, the start of a social shift which resulted in a less-raucous neighbourhood, and perhaps one less flamboyant, less adventurous.

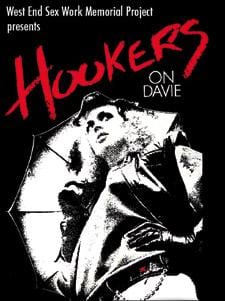

It’s a period explored in one of the most controversial films ever produced in Canada — Hookers On Davie.

The film, released in April 1984, was written by Holly Dale who co-directed it with Janis Cole. It won the Gold Plaque for best documentary at that year’s Chicago International Film Festival and was nominated for a Genie in the best theatrical documentary category a year later.

The decision to shoot the film came after eight months of research by Dale and Cole into prostitution in major North American cities.

According to a Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre film study guide, the West End was Canada’s prostitution capital, with more than 150 sex workers turning “the tree-lined streets into a drive-in brothel open for trade from noon until 4 am, seven days a week.

The turf was split up depending on what johns were seeking. Boystown was centered around Broughton St with young guys cruising cars outside churches. The trannies were in the alleys off Bute.

Little Sister’s co-owner Jim Deva remembers one trannie who would shoot out the streetlights behind Hamburger Mary’s with a slingshot so she could work in the shadows.

The filmmakers had to win the sex workers’ trust. Some ultimately agreed to wear radio microphones as they negotiated with tricks while being filmed by a camera hidden in a nearby van.

The sex workers met — often in The Columbian restaurant above the Super Valu parking lot entrance — to create bad date sheets and to discuss health concerns, self-defense and safety. In doing so, they managed to create a pimp-free environment.

“I was one of the hookers on Davie,” says trans activist Jamie Lee Hamilton. “Back then, the West End and Davie had flare.

“Now it has rainbow flags,” she says. “It takes people to make a village; not banners.”

Throughout the film, the prostitutes talk about the violence they face, the stigmatization they endure and coming to terms with who they are.

“A lot of prostitutes seem like they’re hard people,” says one woman, “but they’re not.”

Mark/Michelle says the street had everything from pushers to little boys. “It’s composed of a lot of things that shouldn’t be there,” she tells the camera.

Later, as the trans prostitutes sit on milk crates behind Hamburger Mary’s, Mark/Michelle sets the stage for what is to come as the politicians and courts move to remove them.

“As soon as they take [the milk crates] away, we’re going to have to sit on the cement. Then they’re going to start taking our clothes. Then we’re going to be left with nothing but the Kraft dinner,” she says.

And from the darkness, an ominous whisper responds: “Then they’re going to take your life force away.”

Deva remembers the lively days of hookers on Davie St well. He says it was part of what made the West End fabulous.

“It was electric and magical,” he says, fondly recalling the days when Little Sister’s could count on hookers plying their trade in the store’s old Thurlow St parking lot.

“It was strange and wonderful. Lots of good energy.

“Now, it’s more to do with real estate prices,” he says.

Hamilton agrees.

She blames the movement of the prostitutes out of the West End on “a movement by some middle-class gay men who wanted to create the West End in their image and be considered normal.”

“They said we were too loud and flamboyant. When we were there it was like Mardi Gras. We contributed so much to the vibrancy of the neighbourhood.”

Hamilton says the presence of the prostitutes brought business into the area, put people in the bars.

“We were the ears and eyes of the street. We secured the neighbourhood.

“The gay guys, the hookers and the seniors were all interconnected,” Hamilton adds. “Then the gentrifiers came in, created a very conflicted time.”

Pushed by the Concerned Residents of the West End (CROWE), in part led by former Vancouver Centre MP Pat Carney, city council brought in the city’s Street Activities bylaw in 1982.

Gay former city councillor Gordon Price is acknowledged by Simon Fraser University researcher Mary Shearman as one of CROWE’s founders.

“Price went on to become a city councillor who remained focused on the issue of prostitution,” Shearman writes. “Price’s tactics and agenda were often questioned by his colleagues, including [local activist Bev Ballantyne] who believed Price was the source of public paranoia and panic.”

Price, however, says the time was one of great frustration.

He says it was the movement of the sex trade off Davie itself into the side streets which began to infuriate residents tired of the noise.

And, he says, the push was on with Ottawa to legalize prostitution, which might have allowed for the creation of a red light district — perhaps in the West End.

“If the hookers had stayed on Davie, they might still be there,” he says now.

It fell to local government to deal with the issue, he maintains.

“The streets are for everyone,” Price says, “and no one group is going to control them.”

“If [government] is not able to demonstrate they had control over the streets, they lose legitimacy,” he adds.

Then came the Jul 4, 1984 injunction by BC Supreme Court Justice Allan McEachern.

University of BC sociologist Becki Ross says the ruling “banned ‘blatant, aggressive, disorderly prostitutes’ from the West End in order to preserve the ‘peaceful integrity of the community.’”

“McEachern described the situation in the West End as an ‘urban tragedy,’ chastising those who ‘defiled our city’ by ‘taking over the streets and sidewalks for the purpose of prostitution,’” Ross says.

By 1984, Hamilton says the push was on to harass the prostitutes and push them east of Granville.

The final scene of Hookers On Davie reflects the sex workers’ outrage at being harassed. Fed up, they and their allies march through the West End carrying placards and banners. “Harcourt is my pimp,” reads one sign.

The 1975-85 period of street prostitution in the West End is now the subject of research by Ross, who is incoming chair of the Women and Gender Studies at the University of British Columbia.

Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, “The Expulsion of Sex Workers from Vancouver’s West End, 1975-1985: A Cautionary Tale” is examining archival and media coverage from the period.

“Without [Hookers On Davie], we would not have a document that includes the voices and images of the sex workers — most of whom are dead,” Ross says. “This is a monument to them.”

Ross says there has also been a push to erect a more visible memorial to those workers in the West End, be it a plaque or a bronze stiletto.

Deva remains critical of the municipal government’s decision to drive the prostitutes out of the West End into what is now Yaletown. “I suspect they used a hammer rather than a scalpel,” he says.

Hamilton agrees.

She says the gentrification in Yaletown pushed more sex workers into Mount Pleasant, down East Broadway and then into the Downtown Eastside.

“The killing fields were created,” she says. “The vigilantes were sending the message to wackos that it’s okay to come down and harm prostitutes. ‘Get rid of them for us.’”

Sadly, she says, it took the crimes of convicted serial killer Robert Pickton to bring the plight of the hookers to light.

“They were literally just swept away and there was little opposition,” Deva says. “They went in different directions in the city. All of us who were there bear some responsibility.”

Ross agrees.

“We argue that the ‘cleanup’ and ‘renewal’ agendas have resurfaced in preparation for the 2010 Winter Olympics,” Ross says. “Since 1975, more than 70 sex workers have been murdered in the Lower Mainland.”

“We are all covered in blood on the Pickton case,” she says. “Anyone who lived in the city at that time is culpable.”

But, she says, “as the memories of the horrors of the Pickton trial fade, we are determined to chronicle the complex contests around urban space, sex, gender, work, love, community, and citizenship in the emerging gaybourhood of the gay West End in the late 1970s and early 1980s.”

Price questions the Pickton connection.

“What if Pickton had picked up his victims in the West End?” he asks.

He brings it back to the intransigence of the federal government on legalizing prostitution.

“If they wanted to legalize prostitution, we wouldn’t have been opposed to it. They just weren’t going to.”

Deva says the forced departure of the prostitutes led to the economic shift in the West End. “It was the beginning of the gentrification, the raising of the rents,” he says. “It’s important.”

Adds Ross: “The West End became not only desexualized and sanitized, but whitened and made safe for [a particular kind of] capitalism, with lethal consequences for outdoor sex workers in the city.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra