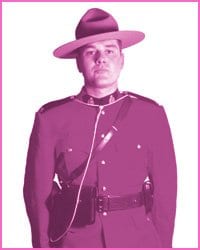

Since first walking into a St. John’s, Newfoundland gay bar in January 2000, Robert Ploughman has traded the vestments for a Stetson, the pulpit for policing.

The first gay man to come out during RCMP training, and the first gay officer to continue serving after coming out, Constable Ploughman knew, as he set foot in that bar, that he had found his flock. He was only months away from ordination as a Catholic priest but knew at that moment he could not reconcile his sexuality with service in the church.

“I always knew I was attracted to men but I never really explored it or worried about it. I walked into the door of the gay bar in St. John’s for the first time in my life and looked around and saw all these guys that looked like normal people. I had no contact with the gay community before that point. I said: ‘My God, I’m gay. I’m gone. I’m finished.’

“In five minutes, my life was completely changed. I knew I couldn’t live a lie in the priesthood.”

Having eyed the ministry since age 12, Ploughman says the decision to leave was painful. Nevertheless, he explored St. John’s gay community and fell in love.

The only other career option in Ploughman’s mind was the RCMP where he saw a chance to serve gays, lesbians, bisexuals and trangenders. “I can reach out and serve this community . . . in a way that has never been done before in terms of an open, gay male Mountie.”

Ploughman, 30, is now stationed at the UBC detachment. Although the east coast remains in his heart, he’s not far from the ocean as he patrols Wreck Beach.

He’s now researching what resources are available to Vancouver’s community and considering what the RCMP can do to build bridges and overcome barriers. He was assigned to film the Aug 4 Pride Parade so his superiors could determine if there was any activity which would prevent members from marching in 2003. Initially, Ploughman had wanted to be in the 2002 parade.

“I had a great desire to honour the gay and lesbian community with that red serge and for people to realize there are openly gay and lesbian members of the RCMP contributing to that legacy of the Mounties and the history. That new chapter is being written by gay and lesbian people.”

The force was concerned about genital exposure in the parade-which is a Criminal Code offence.

Ploughman began his community work as the liaison to Pride UBC, later becoming involved with the Vancouver Police Department diversity committee. From there, he was invited to sit on the community safety committee formed after Aaron Webster’s murder Nov 17. He’s also involved with the Surrey RCMP detachment diversity committee and has attended diversity conferences put on by the Chiefs of Police Association.

Ploughman’s commanding officer, Staff Sergeant Barry Hickman, believes the gay cop is an asset to the force and will help break down stereotypes of the gay community within the force and of the police in the gay community.

“If we do have a major crime in the gay community, he’s an asset,” Hickman adds. “We can strategize on things and understand them culturally. I think he has a promising career.”

The safety committee’s Jim Deva says Ploughman is a good ambassador for both the Mounties and the queer community. He fears, though, that the RCMP will “pulverize and spit out” the constable after several years.

Such a course of action would be a public relations nightmare for the force, Deva warns.

“When you’re the first, you have to be extraordinary,” Deva says. “This is the absolutely ideal person for this role. We should treasure him. He’s very special and unique.”

RCMP E Division spokesman Sergeant Grant Learned acknowledges that uniqueness, saying Ploughman will be able to build bridges between the force and the gay and lesbian community.

He says Ploughman’s coming out at the Regina training depot-“a bastion of straightness”-will live on in force history.

Being the stuff of legend notwithstanding, the constable has a beach beat to walk. Although he understands the historical cultural significance of public sex to the gay community, Ploughman says the beach is a public location and that everyone has a right to enjoy it.

“Any member of the public should feel comfortable to use it and enjoy it. That’s why there’s laws against graphic genital sex in public.”

Deva cautions people against believing that Ploughman can be a cheerleader for either the Mounties or the gay community; the constable needs to find a middle path, says Deva.

In his eight months at Wreck, Ploughman has not seen anyone having sex and knows of no charges being laid. He says he’s not going to crawl through dense bush to find people having sex and that finding private places is a matter of common sense.

“If anybody’s stupid enough to be doing that graphic sex act right in the middle of the trail, then we’ll enforce that law.”

Ploughman says as a Mountie he has to enforce public policy. Signs announcing gay-friendly areas at Wreck might be an idea, he says.

“That’s certainly something I could bring up with GVRD,” he says, “which would be their responsibility, not ours.”

Hickman says Ploughman should use his discretion when it comes to cases of public sex. “If it’s an indecent act in a public place he has to act as a professional.”

Federal NDP politician Svend Robinson doesn’t see Ploughman having a conflict between his newfound culture and the oath he has taken to uphold the Criminal Code.

“He’s a professional and he’ll stand by that,” Robinson says.

The Burnaby-Douglas MP is thrilled to hear about the openly gay officer, recounting past cases of officers being fired for coming out. He recalls interviewing one closeted senior RCMP officer while sitting on a House of Commons committee on equal rights.

“He was in tears about having to live completely closeted,” says Robinson, adding the committee recommended an end to RCMP discriminatory policies in 1986.

With the Vancouver Police Department marching in the parade, Robinson cannot imagine the RCMP seeing a problem in also marching.

With a Master’s degree in divinity and a bachelor’s degree in criminology, Ploughman spent eight years in seminary before having his epiphany.

“I see the priesthood and the RCMP as being very similar: spiritual law enforcement and physical law enforcement. You wear a uniform. Everyone’s either on their best behaviour or worst behaviour when you’re walking around. Everybody lies to you.”

He laughs, though, that he hears fewer confessions these days.

He made his own confession in Regina after his troop received a stern warning from a drill corporal.

“I went to depot with every intention of staying in the closet until my training was over and I was mounted,” he says. The corporal told them one way to get kicked out was to make fun of homosexuals or Newfies.

“I thought to myself: ‘My God, I’m both. I own this place.'”

On the weekends, Ploughman would disappear, leading his troopmates to believe he was being taken care of by an older woman. When he introduced his 24-year-old boyfriend to the troop, jaws dropped.

After the initial shock, he began answering the troop’s questions. For many, he was the first contact with an openly gay man. At the end of their training, the local queer community sponsored a graduation party. The newly minted officers got free drinks. A picture of the troop clad in red serge remains on the wall of a Regina bar. Ploughman was class valedictorian.

“Of course, my gay brothers were quite excited to see me show up with 10, six-foot-two blonde-haired, blue-eyed Mountie cadets.”

Despite a 2001 controversy about recruits being questioned about their sexuality, Ploughman says it never arose in his case. He acknowledges that until 1988, homosexuality was a cause for not being hired as it was considered a threat to being granted a top secret security clearance because of blackmail issues.

York University professor Nancy Nicol is the director of the film Stand Together which examines Canadian gay liberation after RCMP gay witchhunts in the ’50s and the subsequent decriminalization of homosexuality in 1969. Nicol says the concept of an openly gay RCMP officer is new but adds police forces have been forced into change by three things: human rights challenges, ongoing persistence by the gay and lesbian community to create awareness of equality, and official gay-police liaisons. Despite that, she says, entrapment of homosexuals in washrooms and other places by RCMP continue.

“It’s a process of legal and social change which has forced police to stop discriminatory hiring practices,” Nicol says.

UBC RCMP DETACHMENT.

604.224.1322.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra