When Tim Curran became the first gay man to sue Scouting America for inclusion in 1981, reporters often asked him if, assuming he won his lawsuit, he’d return to the program.

The recently minted Eagle Scout from Berkeley, California, always said yes—that he’d love to rejoin Scouting given the chance. But back then, the hypothetical seemed so impossibly remote as to be almost meaningless.

“It’s one thing to say something like that,” Curran tells Xtra. “And it’s another to actually be confronted with the reality of going to a troop, getting your uniform, putting the neckerchief on, getting to a place, spending time there.”

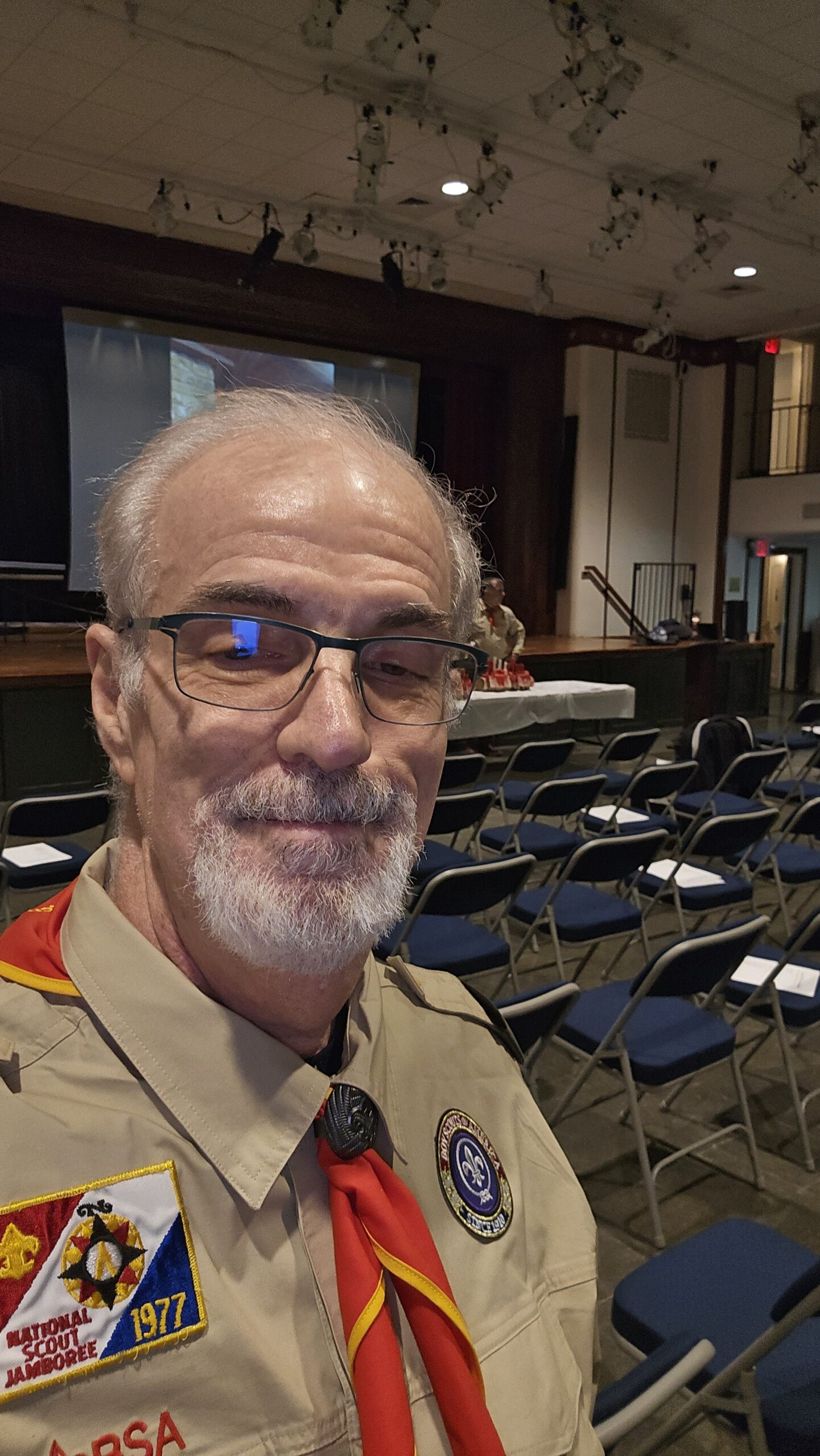

That is, however, the reality that Curran is now living, more than 40 years after he first challenged the Scouts’anti-gay membership policy in court. This fall, Curran became an openly gay adult volunteer for a scout troop in Manhattan.

This milestone reflects the sweeping changes that Scouting America (formerly known as the Boy Scouts of America) has undergone in the last decade in service of inclusivity—changes that the organization has so far been unwilling to reverse. The current political moment, however, poses new challenges: On Tuesday, the Washington Post reported that the Pentagon is demanding Scouting America “return to core principles,” or risk losing its military support.

Curran lost his court battle against the Scouts in the late 1990s, and plaintiff James Dale similarly lost in the U.S. Supreme Court in 2000. But over a decade later, a resurgent grassroots movement led to policy change: The acceptance of gay youth in 2013, then gay adults in 2015. In short order, the organization also allowed trans boys and cis girls.

Curran is now making good on the promise of rejoining post-policy change. He finds himself, a lifetime later, dusting off his camping skills. And he says he’s not doing it as a symbolic act; he’s doing it because he wants to make a real contribution to a local scout troop.

“It really isn’t checking a box or finishing a story or whatever,” Curran says. “I mean, that’s great. I’m happy that that’s happening … But it’s not why I’ll be working with this troop two years from now.”

Four decades in the making

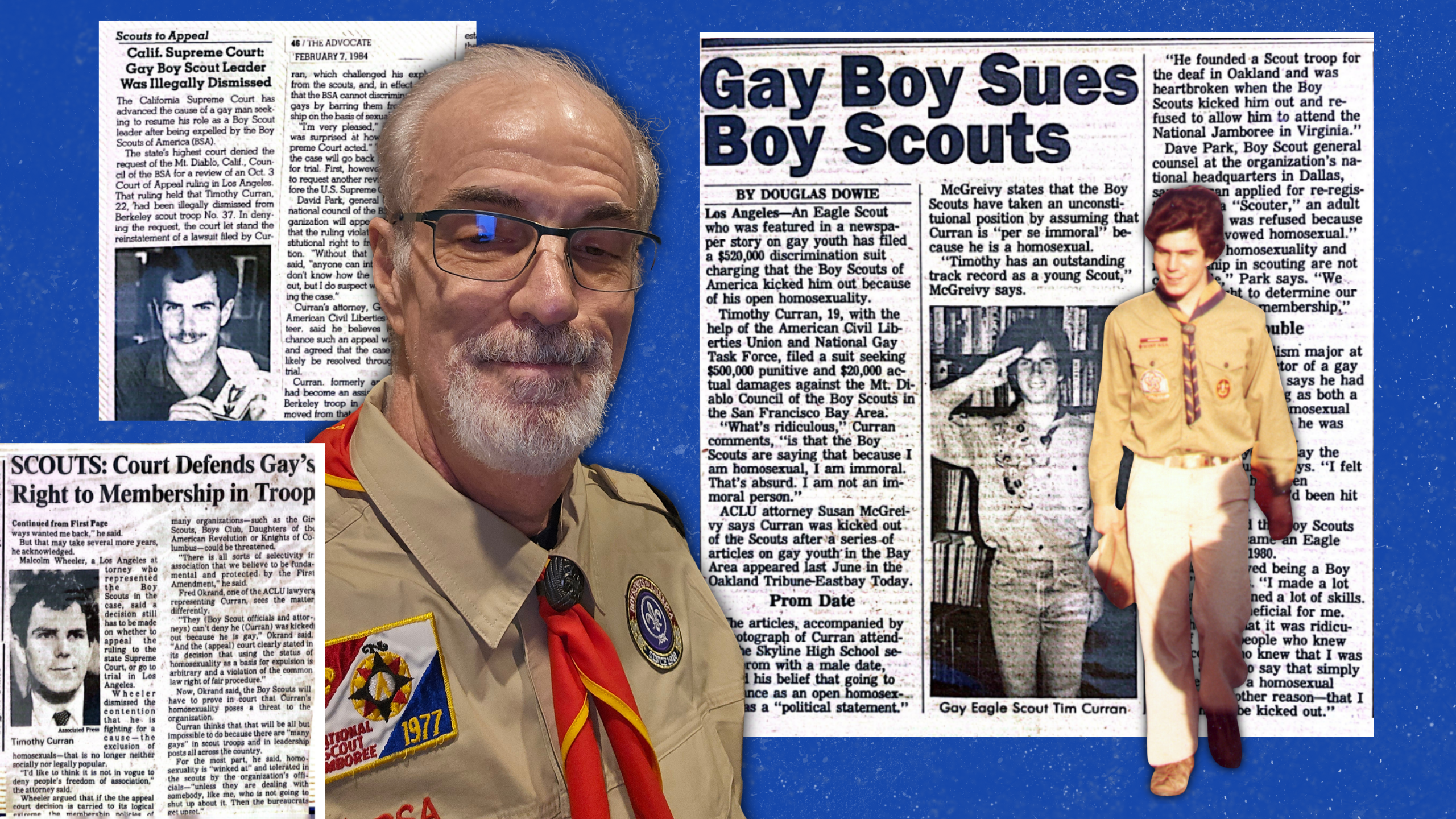

Curran was unceremoniously barred from Scouting for being gay in 1980.

He had joined in 1975 as a (self-described) nerdy 14-year-old. He wasn’t out as gay to his fellow scouts, but found his troop to be somewhat of a refuge from the homophobia he experienced at school. He sailed through the program without issue, earning its highest rank a few days before turning 18. His sexuality didn’t become an issue until, as a college freshman, he applied to be an adult volunteer at a national Scouting event. Here, Curran found that his local Scout council was unwilling to welcome him as a gay man.

Scouting leadership had only recently learned of Curran’s sexual orientation when they read a local newspaper series that featured Curran alongside other gay teens. So, in response to his volunteer application, Curran says he was told that being gay made him “ineligible and unfit to serve.”

He appealed to a regional entity of Scouting and, finding no success there, filed suit against the Scouts in California courts in 1981. But his legal journey would prove to be complex, meandering and, ultimately, unsuccessful. After a trial and several appeals, Curran lost his case—at the age of 36—in the California Supreme Court in 1998. The court found that Scouting did not qualify as a “business establishment,” which was the threshold for being subject to California’s civil rights law, and therefore was free to set a discriminatory policy.

In the meantime, another legal challenger had emerged from New Jersey. James Dale, also an Eagle Scout, found himself similarly kicked out of Scouting for being gay when he was a young adult volunteer. He sued Scouting in the early 1990s, and his case landed in the U.S. Supreme Court in 2000. He too lost, with the justices deciding that Scouting had a constitutional right (the freedom of association) to set its own membership policies.

But this would not be the end of the movement for LGBTQ2S+ inclusion in Scouting. In the 2010s, a campaign called Scouts for Equality emerged, leveraging media pressure to sway the organization. This ultimately proved successful, with Scouting ending its discriminatory policies against both gay youth and adults in the span of a few years.

Read the news coverage of Tim Curran’s legal fight in 1981:

Curran could have rejoined Scouting in 2015, the minute the ban on gay adults fell. And he did look into it: He found a promising troop in Brooklyn, but it would have taken an hour to reach by subway. At the time, Curran was working as a professional journalist on an overnight shift at CNN, making participation in Scouting—or really, almost anything outside his job—nearly impossible, which was also a factor in his decision not to pursue membership as an adult volunteer.

But when Curran was laid off from CNN in March 2024, his world suddenly opened up. About a year later, he joined a panel discussion with me and Dale, to discuss my book Morally Straight: How the Fight for LGBTQ+ Inclusion Changed the Boy Scouts—and America.

It was at the reception after this event that Curran fell into conversation with James Delorey, a member of the local New York City Scouting board. Delorey, learning that Curran had not been to a Scout meeting since the 1980s, pitched him on the idea of finally rejoining the program.

“He would have been completely within his rights to tell Scouting to take a hike,” Delorey says.

He didn’t. Curran submitted an application to rejoin Scouting as an adult volunteer.

Just another volunteer

By late September, Curran was on his way to his first meeting as an assistant Scoutmaster with a troop close to his home on New York’s Upper East Side.

The unit, Troop 662, is led by Antonio del Rosario, a real estate broker in the city who also organizes regional diversity, equity and inclusion efforts for Scouting across a large swath of the northeast U.S.

Curran spent the first meeting, he admits, a little ill at ease. It had been more than four decades since his last one and, having been kicked out at such a young age, he never really had the opportunity to learn what it meant to be an adult volunteer.

He was seemingly the only adult without a kid in the troop. Curran tells me that the natural question from the other volunteers was: Who are you, exactly? Curran says he explained that he had wanted to rejoin scouting for many years, but had been unable to do so because of his busy career as a journalist.

Tim Curran helps set up an Eagle Scout Court of Honor for his new New York City Scout Troop in October 2025. Credit: Courtesy Tim Curran

As for his sexuality, he didn’t exactly announce that either at first. “I was, I thought, pretty clear without wearing a billboard that I was a gay man, but I just didn’t want to go into the whole Boy Scout lawsuit thing, because that’s history,” Curran says. It’s also not a great icebreaker. “In the grand scheme of things, it’s secondary. It’s certainly secondary to what they expect of me and what they want from me” in the troop, he says.

Curran recalls that, as he stood at those early meetings, feeling awkward and having to introduce himself repeatedly, he wasn’t so sure that he’d stick around. But the encouragement he received from del Rosario made the difference. “The welcoming posture that he took and his enthusiasm for having me join was what has energized my whole experience so far,” Curran says.

As he continues to attend meetings and campouts, Curran is trying to get to know people (he made flashcards for names and faces) and brush the cobwebs off his Scouting skills. Del Rosario (who, for his part, had no knowledge of Curran’s history before meeting him) is more than happy to have the extra hands.

“I just throw challenges at him and throw tasks at him,” del Rosario says. “If you give me an inch, I’ll take a mile.” For now, he’s charged Curran with helping scouts check off rank requirements. “I see him just as another incredible human being mentoring our youth,” he says.

At a recent winter campout, del Rosario gave Curran the opportunity for a proper introduction. During a campfire program filled mostly with skits, jokes and songs, del Rosario brought Curran up to talk about why he was banned from Scouting for so long, and then opened the floor to questions from scouts, who Curran says were thoughtful and compassionate.

For the once-banned Scout leader, the moment felt both liberating and grounding. “Rejoining the Scouts, leading as an assistant Scoutmaster and now telling my story to the boys, represents the end of not just a chapter, but an entire volume in my life,” Curran tells me. “All the hopes, dreams, anger and anxiety embodied in this journey, this project, can now be set aside. The feeling of closure is palpable, like a thing I can hold in my hands, put in a box and place on a shelf.”

Now, a new chapter begins: One where Curran will relearn how to tie his knots and build a fire. And he’s loving every minute of it.

Not going back

Looking at Curran’s story today, it might seem inevitable that Scouting would come to accept gay members like him. But Curran doesn’t see it that way.

Scouting America has endured four decades of controversy to arrive at this point: first with the

high-profile court cases of Curran and Dale, and then with the more recent settlement to compensate 82,000 sexual abuse survivors.

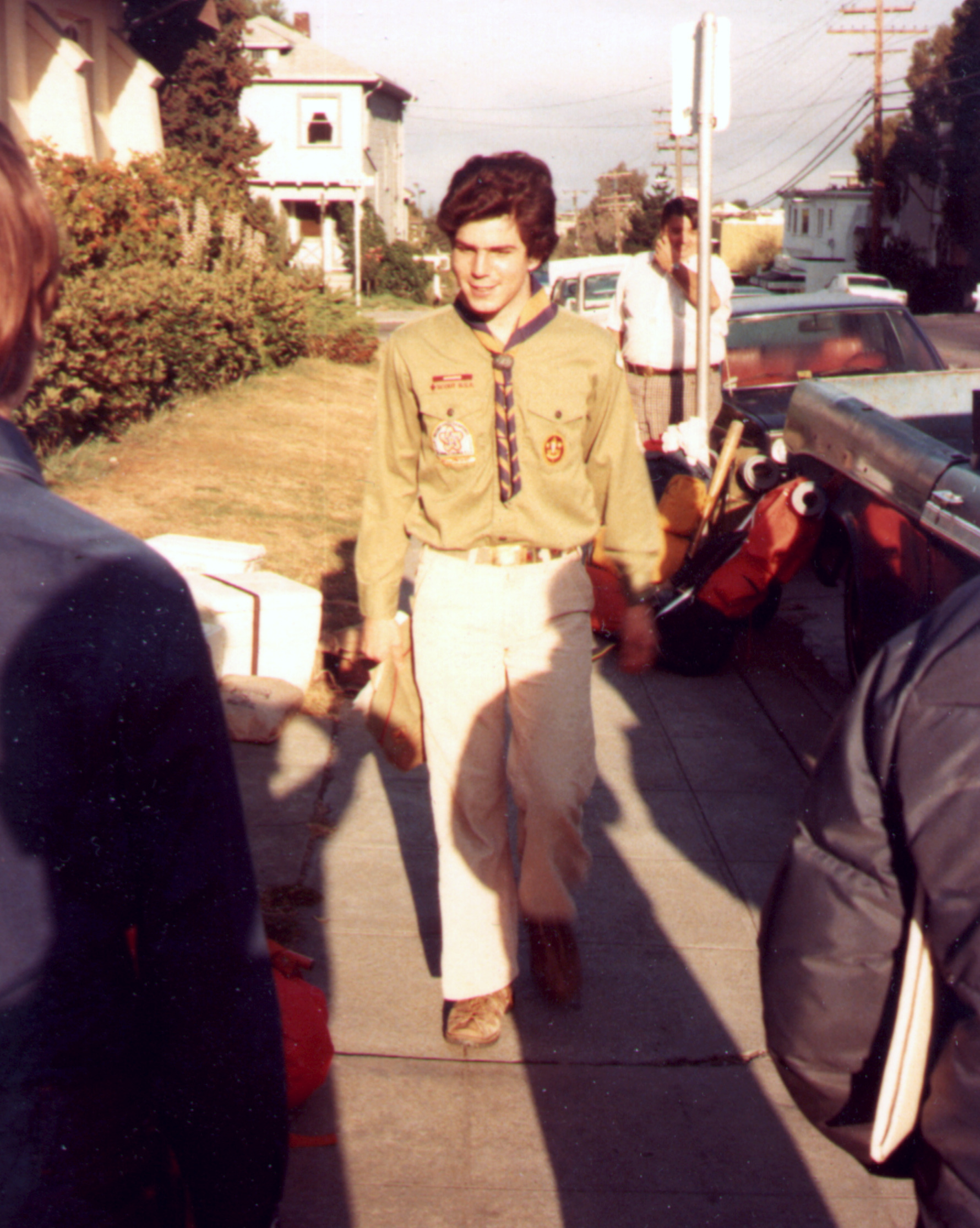

Tim Curran helps load gear for a camping trip with his original Scout Troop in Berkeley, California in 1980. Credit: Courtesy Gil Lundgren

The organization has reached its policies for diversity and inclusion “the hardest imaginable way,” Curran says. “Now Scouting America seems committed to this course of action. And I don’t think that would be the case, but for all of this history that certainly everyone in Scouting leadership knows well.” (Scouting America’s national PR office declined to comment.)

Antonio del Rosario, who himself became an Eagle Scout back in the 1980s, looks at Scouting’s history of banning LGBTQ2S+ people as an unnecessary fight that deprived the movement of people like Curran. “In the time he was banned from Scouting, we missed out,” del Rosario says. “We were robbed of the gift [Curran] is as a human being.”

While a lot has changed politically during Curran’s absence, he reports that very little seems different at the troop level. The uniform design has been tweaked, and this troop has a more regimented style than the one of his youth, but otherwise he recognizes the program he used to know.

“The very fact that I’m allowed back in is a sign that things have kind of moved full circle with the Scouting movement,” Curran says. “So I’m just sort of getting back on the merry-go-round as it comes around to where I’ve been standing this whole time.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra