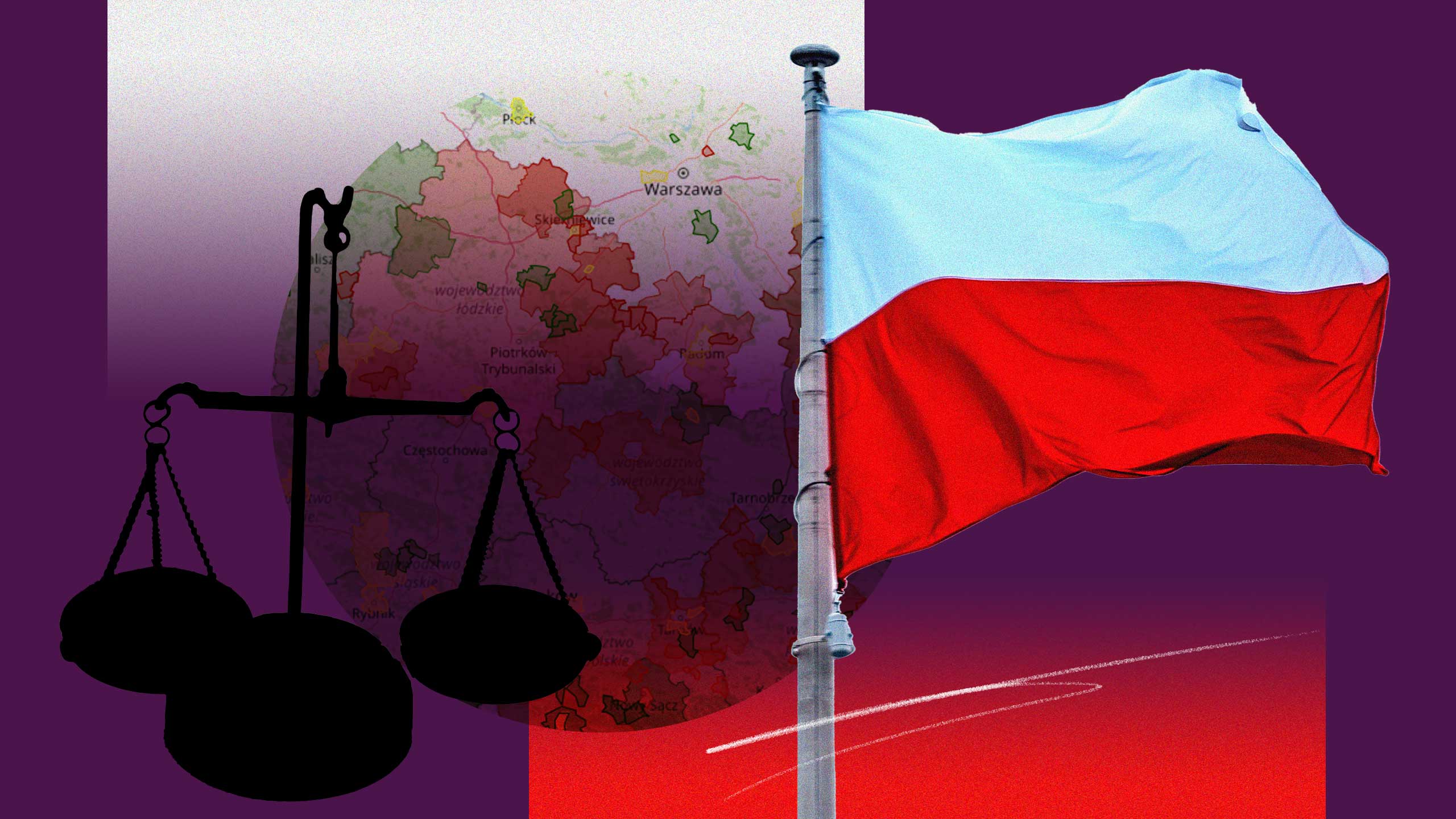

In the face of increasing government persecution of LGBTQ+ people in Poland, four activists have managed to pull off a surprising legal victory.

In December 2021, a group called Atlas of Hate, a research organization that tracks the actions of anti-LGBTQ+ governments across Poland, won a court case against the local government of Przasnysz, a town of about 20,000 people located north of Warsaw. The civil case was heard at a district court of the Masovian voivodeship (a voivodeship is similar to a province).

The presiding judge, Grażyna Szymańska-Pasek, said in her decision that Atlas of Hate exercised its constitutional freedom of speech and freedom of expression, as granted by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, and was guided by the public interest in its project of informing the public about anti-LGBTQ+ government policies. Szymańska-Pasek agreed with the activists’ arguments not only in terms of the law, but in the organization’s definition of family as not being simply a heterosexual institution: “The family is not just a father, mother and children. It is also, for example, a mother raising a child with her partner or a father raising a child with his partner,” wrote the judge.

The court case was sparked after a 2019 decision by the Przasnyski County Council to adopt what’s called the Local Government Charter of Family Rights. The charter, sponsored by the influential and conservative Roman Catholic group Ordo Iuris, had the town commit to the “protection of marriage, being a union of a man and a woman, as well as the family, motherhood and parenthood, the right to protect family life, the parents’ right to rear their children in accordance with their own convictions, and the child’s right to be protected against demoralization.” The document was presented as “an expression of the values certified in the Constitution of the Republic of Poland, including the identity of marriage as a relationship between a woman and a man, the defence of the family and parenthood.”

Przasnyski’s adoption of the resolution, which has been passed by dozens of governments in Poland, did not go unnoticed. Atlas of Hate has been collecting documents about local anti-LGBTQ+ resolutions, some of which are used to deny all forms of aid or funding to LGBTQ+ people, ban the participation of LGBTQ+ organziations in local political life and prevent anti-discrimination education in schools. Some resolutions have declared jurisdictions to be “LGBT ideology-free zones,” meant to broadly signal that LGBTQ+ people are unwelcome and to prevent queer and trans events. The Atlas activists compile these jurisdictions into an online spreadsheet and publish them on an interactive map to summarize the current situation for every voivodeship in Poland with the aim of drawing attention to these policies.

But when Atlas tagged Przasnyski on their map, the county council accused them of violating their good name, defending the adoption of the Charter in support of “normal values, in favour of the family.”

“They also spoke about the alleged demoralization of young people, although, of course, they did not present any proof,” Jakub Gawron, a founder of Atlas of Hate, told Xtra. The county filed a civil court case on Jan. 20, 2021, and six months later, on July 20, the first hearing was held.

When the court dismissed the lawsuit on Dec. 29, 2021, it also ordered the county to pay Atlas’ court costs, about 1,000 euros (about $1,400 CAD).

“We are happy about the sentence. It’s a big win for us,” says Gawron. “It gave us a lot of hope for the future and it’s a good prognosis for the next trials we have to face against other counties.”

“Even a small informal activist group can win against a law foundation with a multi-million dollar budget that co-operates closely with an authoritarian state.”

The struggle of the four activists is not over yet. Przasnyski’s resolution is still in effect and the county has already announced an appeal, so the case will be processed by an appeals court. Depending on the outcome of the appeal, either party is able to file an extraordinary complaint to Poland’s supreme court. Meanwhile, the Atlas of Hate is also being sued by six other local governments they tagged on the map, who are accusing the organization of violating their good names. Together, they are demanding total compensation of 30,000 euros (about $42,000 CAD).

In the Przasnyski case, the judge engaged with the larger context of oppression faced by the LGBTQ+ community in Poland in recent years. “The statistics state that 68 percent suffer from verbal abuse, 12 percent have violence, over 50 percent hide their orientation, 30 percent suffer from depression,” she wrote.

During the trial, Przasnyski county authorities did not explain why the resolution was adopted, instead arguing that they weren’t discriminating against anyone or inciting hatred. But the judge wrote that these kind of resolutions have been adopted without a legal basis and interfere with people’s freedoms and rights, calling them discriminatory in nature by excluding people identified as LGBTQ+ from the community.

Reacting to the decision, Gawron said it also showed, along with the court’s support of free speech and citizens’ right to be informed about the activity of governments, the importance of an independent judiciary in Poland.

“The victory is a very good signal for us,” says Gawron. “It shows that even a small informal activist group can win against a law foundation with a multi-million dollar budget that co-operates closely with an authoritarian state.”

The foundation he’s referring to is Ordo Iuris, which has been a driving force behind conservative legislation across Poland. The organization’s lawyers not only provide jurisdictions with draft templates of anti-LGBTQ+ policies, but launch court cases against Polish activists who fight for LGBTQ+ rights and provide legal assistance to municipalities which have adopted its policies. Its Municipal Charter of Family Rights, released in 2019, was adopted by 34 municipalities in less than a year.

The resources and money Ordo Iuris brings to the table has made being an activist in Poland extremely difficult: they are always in the spotlight, and as soon as they make a misste, they face huge legal risks, including detention. For example, in 2020, 48 people were arrested during a protest in Warsaw in solidarity with Malgorzata Szutowicz, a non-binary activist better known as Margot, who was jailed before trial on two charges—one involving hanging rainbow banners over statues, and another for allegedly damaging an anti-abortion campaigner’s van. Margot, who was released after about a month, went on a hunger strike while in jail, which triggered the protest.

The LGBTQ+ community in Poland has faced increasing discrimination as the country’s ruling party, the right-wing and Roman Catholic-oriented Law and Justice (PiS) party, continues to implement anti-queer and -trans policies. This part of the anti-LGBTQ+ narrative began during the 2019 parliamentary election campaign when ultra-conservative politicians adopted a strategy of using LGBTQ+ issues as a scapegoat to divert attention from more important issues. PiS leaderJarosław Kaczyński has described the LGBTQ+ movement as “a threat to the very foundations of our civilization,” while President Andrzej Duda, also a member of PiS, declared “LGBT ideology was a greater threat than communism.” Leader of the far-right foundation Życie i Rodzina, Kaja Godek, who ran for European Parliament in 2019, has said, “Gays want to adopt children so they can molest and rape them.”

According to the Rainbow Map produced by ILGA-Europe, Poland is the worst country in the European Union for LGBTQ+ people based on factors like marriage equality, non-binary recognition, hate-crime laws and health and education policies.

At the moment, the Polish parliament is debating two bills. One is the “Stop LGBT” project, which would ban Pride marches and other public gatherings that “promote” non-heterosexual sexual orientations and diverse gender identities. The second (already approved by one of the chambers of Parliament) would reform the school system by hindering sex education and the promotion of sexual identities in schools. The school reform would also allow the possibility of dismissal for teachers who openly speak about issues of sexual and gender identity. The latter bill mirrors that of Russia’s anti-LGBTQ+ propaganda law, which, among other restrictions, prohibits materials in the classroom that refer to LGBTQ+ people, organizations or ideas.

Meanwhile, more than 100 Polish cities and provinces have declared themselves LGBT-free zones. “Legally these statements are symbolic and worthless; however, it is a strong attack that affects the mental health of the LGBT community,” explains Rémy Bonny, an activist and the executive director of Belgium-based queer advocacy organization Forbidden Colours. “The percentage of people with depression, suicidal thoughts, taking antidepressants, going to therapy and considering leaving Poland is growing, particularly in the self-declared LGBT-free zones provinces.” The current atmosphere is particularly harsh for LGBTQ+ youth, who generally cannot count on acceptance of their identities by family, schools or workplaces.

Still, Bonny prefers to focus on the positive, the changing attitudes of Polish people. “Because of the government’s anti-LGBT attacks, LGBT people are actually becoming more visible, and also they are attracting more acceptance,” he says. Five years ago, just 30 percent of Polish citizens were in favour of same-sex marriage; now it’s about 50 percent.

“Especially in big cities like Warsaw, Krakow, Poznan, Gdansk, we can feel a nice and quiet atmosphere,” Bonny says. “It’s safe for same-sex couples to walk hand-in-hand. In the countryside it’s not like that, but in society in general there’s a positive growth, a good sign for the future where things can change, thanks to a united and strong and progressive and liberal opposition. Even conservative people are becoming more accepting.”

Gawron says government actions have definitely increased activity by activists. “In 2019, before the pandemic, 20 equality marches were organized all around the country,” he says. “Activists built allied networks and established international contacts. For example, we use social media to publicize what’s happening and to attract and inform media, NGO, politics and everyone who can be potentially interested.” In many cases, these activities are paying off. Gawron says almost 20 anti-LGBTQ+ resolutions adopted by local governments have already been repealed in the last two years.

The ruling in favour of Atlas of Hate can be added to those victories.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra