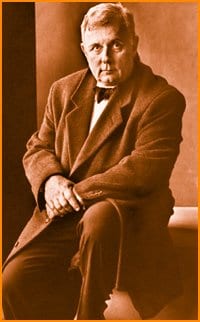

Our first attempt to interview Edmund White by phone from his New York apartment was interrupted before it began by the arrival of his work-out instructor. We called back 90 minutes later to find out he’d not only finished his workout, but also squeezed in writing a book review for the Los Angeles Times, something he’s been doing a lot since returning to the United States after living 16 years in Paris. Praised as the best English language gay novelist of his generation, White has developed a worldwide audience since first garnering significant attention with the publication of his third novel, the semi-autobiographical A Boy’s Own Story in 1982. Known best as a chronicler of gay men’s sex culture, White turns to a fact-based 19th century historical novel in his latest release, Fanny: A Fiction. He is reading at the Vancouver International Writers & Readers festival this month.

Xtra West: Many of us who are fans of Edmund White’s novels and journalism enjoy your writing partly because you deal with gay sex in a realistic, honest fashion, acknowledging we’re a sex-based culture. What inspires this frank writing?

Edmund White: I once had this idiotic class of graduate students in Texas in the creative writing program. They told me they couldn’t teach A Boy’s Own Story to their students because of the ‘child abuse.’ I said wait a minute! There’s a 16-year-old having sex with a 14-year-old. The 16-year-old is getting fucked by the 14-year-old. The 16-year-old is gay and the 14-year-old is straight but just using the other guy to get his rocks off. Who’s the child and who’s being abused? I don’t understand this. It just seemed to me the height of politically correct folly.

XW: You continue to deal frankly with matters sexual. What’s your inspiration?

EW: It’s the truth! I’m interested in the truth. It seems to me most people interested in sex write pornography and I hate pornography. It seems so false to me; it has to be written in formulaic language or else it doesn’t get people off. Real writing about sex is done by very few people, it’s oftentimes comic, it’s almost never erotic in the sense that it arouses you or can lead to a climax. It’s a realistic examination of what really goes on in people’s heads when they actually have sex, which I think is almost unexplored territory.

XW: Why is that? We write about everything else. Why is so little written about the multiplicity of gay sex?

EW: I think it’s because there are two sources for gay fiction: pornography. Men in the ’30s and ’40s and ’50s could read it and get off; it was a time when they couldn’t have real encounters because it was so hard to meet people. The other kind of gay literature that was written was the confessional, a plea for sympathy to the straight reader. A lot of today’s gay literature still reflects those two sources.

What happened in the 1970s with the creation of gay lit by Larry Kramer, Andrew Holleran and myself, was that for the first time people were addressing gay readers with gay fiction.

XW: I cried my way through The Farewell Symphony. It was a really beautiful tale of male love and lust and the hope for a better world turned sour with AIDS. What kind of world do you think gays could have created if we hadn’t lost so much of your generation to AIDS? There was an energy, such an excitement, so much happening there.

EW: Let me take that question in a different way. What I think happened is that upper-class and upper-middle-class gays that had power and money never were involved in the gay movement in the 1970s because they had nothing to gain by it and could only lose prestige, power, position and so on by becoming visible. Then in the 1980s AIDS outed those people because either they became sick, or their lovers or friends. Also, a lot of straight people were taking up the cause, like Elizabeth Taylor and company, so it became kind of chic. In any event, they didn’t have that much choice so they became involved in the gay movement. And it was a time when the whole society was moving to the right, with the Reagan years in America. The whole idea of assimilation became the cornerstone of the gay movement, and you had these heavy breathing, powerful gay men taking over; men who never in a million years would have been involved in gay liberation before, or any kind of movement stuff.

I’m not sure it’s cricket to even say it, but my feeling is that a lot of people who were experimental sexually, in the sense they were having sex with a lot of people or were willing to try being a bottom-in other words, those who were pretty polymorphous in their behaviour-those were the ones who died because of a series of medical accidents around the way you get AIDS. Whereas the squares, or the ones who were timid to get laid or were married to some partner they were faithful to, those were the ones who survived and led the movement. In other words, it seems to me there were about five different factors that conspired to shift the whole thing into the mainstream and to the right.

XW: We lost our very best. The ones who experimented and had vision?

EW: Yes. The net result of it is that the world that might have happened if we had not had AIDS would have been very interesting. I think there would have been a much more consistent and confident challenge to the marriage model. And I think that there would have been a kind of triumphalism in gay culture that I think just didn’t happen. After all, one-third of people in the United States are born-again Christians. And I think a lot of gays lost their nerve. The mid-1980s was a real dark night of the soul.

XW: Have you given up hope for a different model emerging from gay male sex culture, free love and a culture of close friendships-some of the themes of your novels? Or have we become too assimilationist?

EW: Strangely enough, it turns out assimilation isn’t as easy as people thought. Look at the fuss gay marriage has raised. If you’d asked me seven years ago, I would have sneered at gay marriage. But now, gay marriage was an essentially easy thing to get passed in Europe (because Europe is a non-practising continent), but in the United States at least religion goes on and on.

When The Farewell Symphony came out, it got a nice reception in France and England and Germany and different places. But in America, it was very much attacked by the gay press, and also by the straight press. Larry Kramer attacked it violently in The Advocate. This book, which was a celebration of the golden age of promiscuity in the 1970s, was denounced as being dangerous and poisonous for the young, a bad influence and so on, by all these American gay leaders. It’s only now, coming back from a gay literary conference in Provincetown this weekend, that I’m gratified. People came up to tell me they’re teaching The Farewell Symphony in gay-lit courses in these remote little places in Colorado and so on.

It moves me so much because I think it’s a good book and I thought the reception by gay leaders was so unfair.

XW: I think it’s the finest gay novel yet written. But that brings me to Larry Kramer. You’ve always avoided demagoguery in your novels and you’ve been criticized by people like Kramer who put the politics up front and one goes looking for a magnifying glass to find the art. You say you put the art first, but I don’t think you stop at the art, do you? I don’t think I’ve read any of your fiction or non-fiction that didn’t have an important message written into the story.

EW: I think that homosexuality turns out to be one of the most interesting things you can write about. If you want to understand heterosexuality, you have to study homosexuality. If you want to understand modern European history, you have to study the persecutions of gays and, yes, Jews and women and gypsies. But certainly gays called forth the most rhetoric, the most vile, the most unbelievable hatred.

XW: How do you balance the art against the message?

EW: I’ve always felt that truth is an essential ingredient of beauty. I think anyone who writes as part of a minority group, like Toni Morrison or whoever, you cannot help but know that somebody’s looking over your shoulder to see whether it’s true to life of the experiences of black Americans, and so on. You can deliberately reject that kind of inner censor which is operating on you, but you still can’t help being aware of it. It’s always there.

I early on rejected the idea of positive gay role models. In the early days, when A Boy’s Own Story came out in ’82, there were still some of those old Stalinist gay critics left who would say things like, ‘This boy betrays his gay teacher at the end and he’s not a very attractive personality.’ I’d say, wait a minute, he’s growing up in the 1950s and going to a Freudian psychiatrist; why would someone growing up in a deforming era not be deformed? The most powerful political message is to show how that period deformed people, not how they could emerge as ideal human beings out of a totally destructive environment.

XW: You ended The Beautiful Room is Empty at the Stonewall Riots almost with a plea for the emergence of gay media to report on issues important to our own lives. What do you think about what’s happened to gay media in the US in the last few years?

EW: I think there was this kind of flowering of neo-conservative gays, whether it was Bruce Bower or Andrew Sullivan. But they don’t seem too prominent any more, do they?

XW: No, but there doesn’t seem to be a generation of young gay liberal writers emerging to replace them.

EW: No. The funny thing is I think that kind of neo-con conservatism has actually gotten out of touch with the actual gay population, which I think is a lot more thoughtful. AIDS was so scary it called forth a lot of the more moralistic sides of America. Being sex-negative seemed fully endorsed by the medical crisis. Actually, it wasn’t. Closing down the baths, closing down the backrooms, saying people should only have monogamous sex within relationships led to a lot of lovers infecting each other because they thought they didn’t need to practise safe sex. But they were lying about their outside activities.

The media is sort of representative of the dumbing down of America and the shift to the right that certainly happened in the 1980s and ’90s. I like to be optimistic and believe that people’s disappointment with the Bush government and its lies about Iraq, and the beginning of criticism of Bush which has been strangely absent for three years, that this will fan the flames of some real critiques of our society.

XW: Which brings us around to your latest novel, Fanny: A Fiction. Up to now you’ve built your reputation on the sheer fearless personal honesty of your novels as you explore life for gay men. Fanny has a very different feel in comparison. It’s almost a harkening back to the lighter style of your first novel, Remembering Elena. What are you up to?

EW: I moved back to America five years ago after being in France for 16 years. My discovery of America is roughly parallel to Fanny’s. Looking at your own country through the eyes of a foreigner is something that happens when you’re repatriated.

Another thing is I felt I was ready to take a break from the autobiographical theme. There’s a kind of show-offy virtuoso side to me that I love trying to do this. Whether I did or not I don’t know. It was just wanting to be unpredictable.

The way we commodify writers and give them one thing to do and do it over again is part of the same system that is reprehensible and we should always struggle against. In other words, people should be many different kinds of people.

XW: The novel’s radical character, Frances Wright, is someone I expected you to be very sympathetic to because of your own politics. But you point to her lack of humanism as outweighing the good she did.

EW: This woman was one of the most radical figures in American history and nobody remembers who she was. I definitely started out intending to celebrate her.

XW: What turned you against her?

EW: Partly I got captured by Mrs Trollope’s point of view. But also, I thought about some ’60s radicals I had known, like Susan Sontag for instance, who seemed to me to have ruined their own lives and cast a lot of bad vibes all around them, partly because they clung to unbending principles and didn’t take into account ordinary human differences and suffering and so on. There was a lack of heart about certain ideologues of the ’60s I had known.

It’s not just a dichotomy of right vs left. I’m also interested in the dichotomy between persons of rigid principles and persons who are willing to bend to the point of hypocrisy but are survivors.

XW: So the conflict between the pure idea and the reality of human flesh and blood. But could there have been a third character in there who was an idealist but treated everyone around them with respect and was a true model for how we create a better world?

EW: Maybe that’s the third position we have to triangulate ourselves out of these two elements.

XW: You trying anything new in sex these days?

EW: I’m having an affair with this sort of sadistic couple, where I’m sort of their slave. But it’s terribly civilized in a sort of Sade way because they are real gentlemen and they pay me dinner. And they’re always teasing me that they’re going to start paying me for sex. They think I have such low self-esteem that I should be paid. Even though they’re very young and cute, they think that’s the way it should go. But I find them very charming and interesting and fantastically hot.

I’ve been having two other affairs and I’m living with someone who I’ve been living with for nine years and who’s my lover. So, I’m certainly keeping up the tradition of having multiple affairs.

I think there’s a problem with Platonism in our society, which is the belief that there’s an ideal that you should strive for, and that when you reach it you should stay with it for the rest of your life because you’ve reached perfection. Whereas I believe in restlessness. And I think people must change. So when I meet a couple who say they’ve been together 22 years, I ask, ‘aren’t you overdoing it?’ How can you possibly grow if you stay with each other that long? Though I’m going on nine years with my boyfriend, and I love him and I certainly don’t want to give him up, I would feel rather constrained if we couldn’t have other relationships outside our marriage.

EDMUND WHITE.

Vancouver International Writers & Readers Festival.

Oct 24, 25.

www.writersfest.bc.ca.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra