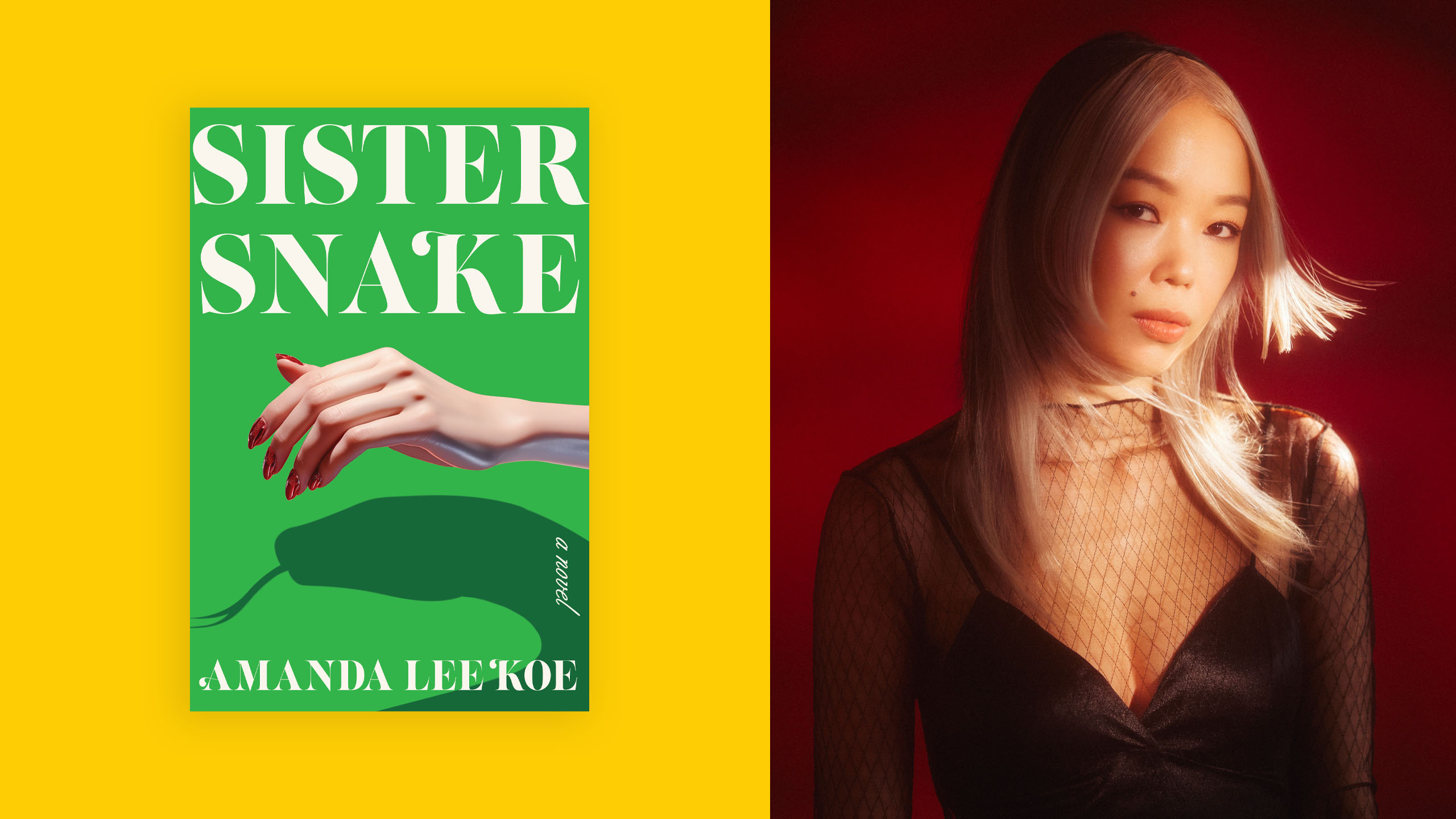

Amanda Lee Koe’s new novel, Sister Snake, is an energetic, queer retelling of a well-known ninth-century Chinese folk tale, “The Legend of the White Snake.” Lee Koe, who grew up in Singapore and is now based in New York, is the author of two previous books: Ministry of Moral Panic, a short story collection; and Delayed Rays of a Star, her first novel, which fictionalizes the lives of actors Anna May Wong and Marlene Dietrich, and director Leni Riefenstahl. She is therefore no stranger to reinterpreting and upending stories that people already think they know. Here, she reimagines the classic tale of shape-shifting and immortality through a distinctly queer, feminist lens. The result is a fun, clever mash-up of queer pulp, magical realism, time travel and body horror, with a charged serpentine sisterhood at its centre.

“The Legend of the White Snake” is one of China’s Four Great Folk Tales, with early versions of the myth focusing solely on the story of the white snake: she falls in love with a male scholar and succeeds in her desire to become human; a Buddhist monk opposes the marriage between a human and an animal spirit, and imprisons the white snake under the Leifeng Pagoda, on the banks of West Lake in Hangzhou. Eventually, another character made her way into the story: the green snake. In one Chinese opera version of the story, Green Snake rescues White Snake from her imprisonment by the monk. In these versions of the tale, Green Snake becomes the faithful and devoted companion of White Snake, who is the story’s protagonist. In Sister Snake, Lee Koe smartly chooses to give equal voice to both snakes—Green Snake gets her own point of view, and it doesn’t always show White Snake in the kindest light.

This isn’t the first time that Green Snake has been granted a leading role in an adaptation of the legend. Green Snake, the 1993 film directed by Tsui Hark, based on the novel by Hong Kong novelist and screenwriter Lillian Lee, foregrounds the younger, more rebellious Green Snake (played by Maggie Cheung). The film’s narrative parses the friction between the snake sisters, stemming from the desire of White Snake (Joey Wong) to live as a human, versus Green Snake’s chafing against the rules and limitations of human life. Lee Koe updates this volatile sisterly relationship for the 2020s as the tension between the two snakes-turned-humans plays out against the backdrops of 21st-century New York and Singapore, two cities as different in character as the protagonists themselves. There is plenty of passion, betrayal and comedy as the two snake spirits, who have been living as immortal humans for the past four hundred years, try to figure out their fraught, centuries-spanning relationship.

Sister Snake opens with the snake spirits living as humans on opposite sides of the world: Green Snake, known as Emerald in human form, lives in New York with her chaotic but sweet gay artist roommate Bartek, and makes ends meet via a sugaring app. She is estranged from White Snake, known as Bai Suzhen, or Su in human form, who is currently married to Paul, an up-and-coming politician in rules-bound Singapore. Their estrangement has lasted for the past forty years or so, and stems from their opposite ways of seeing the world. Emerald is pleasure-driven and curious, always seeking out the counterculture wherever and whenever she lives (she fondly recalls the Harlem Renaissance as well as the cabarets of Weimar Berlin). She’s actively queer, pursuing lovers of various genders throughout her centuries on earth. In present-day New York, she dresses in skin-tight green minidresses; her profile on the sugaring app reads: “You can’t choose your father but you can choose your daddy. The only hair between my legs should be your beard ;).” Su, meanwhile, is obsessed with rules and regulations—she dresses in “immaculate Chanel neutrals” and chooses to live in wealthy Singapore society because of how clearly delineated it is. Its predictability makes her feel safe, even as it subjects her to the authority of her husband and other men. Emerald laments that her sister has become a “Stepford wife” with “a long line of deceased husbands,” and wishes that Su would be more independent as a human woman.

It turns out that the two are not blood sisters—they met as snakes more than a thousand years ago. White Snake was assaulted by a gang of male snakes back in Hangzhou. Green Snake found her after the attack and nursed her back to health. After this, White Snake longed to become human, to escape what she now saw as the violence of snake nature; so Green Snake procured the magic lotus seeds that would allow them both to shape-shift, even though she herself didn’t want to become human. Her love for White Snake trumped her own desires. In their long years of being human, Su has often rescued Emerald by watching over her and bailing her out when she needs it. This pattern of rescuing one another has repeated over and over—but instead of uniting Su and Emerald, the push and pull of their relationship creates an abyss between them. They have the kind of fraught romantic friendship that will be familiar to many queer people—except that it has lasted for centuries. Emerald longs to return to snake life with Su, missing its raw simplicity: “eat, fuck, kill.” When she looks at Su, she thinks: “This is [my] person, across time and space.” But Su is horrified by all evidence of wildness, still traumatized by the attack all those years ago. She hides within Singapore’s “controlled sophistry.” She believes that “[u]nder the right set of conditions, you can remake things about yourself that aren’t possible.” She loves Emerald too, but her desperate need to feel safe gets in the way of their happiness together.

The snakes need to feed on qi, the vitality they can suck from living bodies through the mouth. Emerald siphons qi from unsuspecting sugaring clients—she takes what she needs without killing them. Su finds this method to be uncouth, preferring to subsist on the qi of animals, which is never quite sufficient. Throughout the book, Emerald more willingly accepts her plight as a snake spirit in human form, while Su does her best to fight all of her snakelike instincts. Emerald is as brazen as Su is genteel. In New York, she doesn’t even bother lying to people about her history, realizing that Americans aren’t very concerned with distinguishing truth from lies anyway: “the aspirational deceit and drama of the land of the free [is] a convenient place for an immortal to let it all hang out.” Emerald doesn’t care about observing rules or norms, and the people she encounters and befriends are much more interesting to read about than the people Su surrounds herself with. Su spends her time with a gaggle of wealthy women whose group chat name is “the Spice Girls,” and her bureaucrat husband, none of whom she can reveal her true self to. Emerald’s best friend and roommate, Bartek, though he comes off as a little vapid sometimes, provides both comic distraction and unshakable friendship, even when Emerald reveals herself to him as an immortal snake. When Emerald lets loose and swallows an entire carton of raw eggs in front of him, he takes it in stride: “You’re basically paleo. No big deal.” Queers love other freaks, after all.

When Emerald loses her temper on a date with an orientalist sugaring client, and switches into her snake form to attack him in the middle of Central Park, Su sees the news story and convinces Emerald to come live with her and her husband. Emerald reluctantly obeys—Su is the only person who can rein in her rebellious nature. In Singapore, quickly bored of Su’s bland surroundings, Emerald befriends and then develops a romance with Tik, a sweet Malaysian butch who works as Su’s driver and bodyguard. Tik takes Emerald to the parts of Singapore that Su and her husband would never dream of visiting: the less glamorous neighbourhoods full of strip bars and delicious Indonesian food. Tik and her on-again-off-again girlfriend, Ploy, an enterprising young Thai woman who dances at the local bar, are far kinder to Emerald than anyone else in the city, including Su, who keeps her at arm’s length.

However, things are not all as they seem. Though Su worries constantly about Emerald losing control, she eventually reveals herself to be the more vicious one. Emerald reminds Su that she is a white krait, which is far more dangerous than Emerald’s green viper. “Underneath it all you’re a cutthroat cannibal,” Emerald says. Kraits are known to feed on other snakes and reptiles, but Su tries to repress her nature. Emerald is appalled to learn that in addition to swearing off human qi, Su has avoided changing her snake skin for the past eight years. When a surprise serpentine pregnancy upends Su’s carefully constructed life, the two snakes must learn to put aside their disagreements and past wounds and rely on one another again. This will prove difficult when Su’s self-repression causes her to act with explosive violence, putting her relationship with Emerald into serious jeopardy.

Sister Snake is a propulsive read, playful and serious in turn. Lee Koe is equally comfortable in the realm of contemporary slang and comedic timing as she is writing more lyrically about the snake sisters. One passage will have Emerald recalling a “Ming dynasty situationship” with a monkey spirit living as a human; the next will describe the two snakes’ love of moving through the Singaporean jungle, in beautiful, sensual detail. There are plenty of jokes about whether the snakes are “passing” as human; Su chastises Emerald for letting the slither back into her walk, or for letting her speech become too sibilant. Comedy can quickly switch to horror when one or both of the snakes goes on the attack, or shape-shifts in front of terrified humans. This game of contrasts gives the novel its energy—Emerald and Su are opposite but alike, pitted against one another yet deeply entwined. New York and Singapore present two versions of the contemporary metropolis—the messier, more chaotic New York and the streamlined, law-abiding Singapore; yet Lee Koe reminds us that both cities are affected by the forces of global capital and gentrification. The humans in both cities are subject to similar plights: crackdowns on migrant workers, unaffordable housing, wealth inequality, a lack of reproductive rights. Living as humans means the snakes must contend with these issues as well.

At the heart of the book is a mantra: “This body itself is emptiness. Emptiness itself is this body.” This is the mantra that the two snakes meditated on for hundreds of years, as they prepared to join the human world. It provides a key of sorts to the novel, an anchor amid the chaos. Sister Snake asks how we can live with the past without letting it control us. How can we embrace the fearful, aggressive parts of us without destroying ourselves or the ones we love? What do we do when our bodies remember our past hurts, no matter how far we travel through time and space to get away from them? In giving shape to these questions, Lee Koe offers us a thoughtful queer retelling of a classic tale. It’s a lively read full of contrasts—heavy enough to stop you in your tracks, light enough to keep you slithering forward.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra