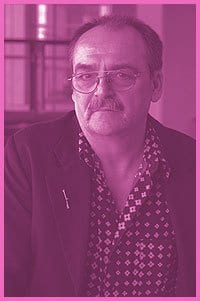

The mere thought of a sex offender registry gets Ron Dutton’s antenna up and working. “Invariably, when these laws are put into place, the people who get nailed are sexual minorities,” says the keeper of BC’s gay and lesbian archives.

No surprise then that Bill C-16, the legislation responsible for the new national sex offender registry implemented last December, immediately drew his attention.

The registry requires people who have been convicted of certain sex offences to register with local authorities, who will then add their names to a national database. It’s supposed to provide police with a list of known sex offenders (especially ones considered likely to re-offend) in a given radius to aid with investigations.

Dutton believes that while sex offender registries are often created with good intentions, there is always an inherent possibility of the laws being applied unfairly.

And he’s not talking in the abstract: he’s seen this happen before.

Many people aren’t aware that in the early 1980s, British Columbia’s Social Credit government introduced a provincial child abuse registry of known and suspected child abusers. Its goal: to combat sexual crime and produce prosecutions.

A complaint from almost any source would get someone placed on that registry, no conviction required. The registry did not demand that the accused be formally notified when he or she was added to the list, and if this information was somehow discovered, the accused had no hearing or appeal rights.

The Social Credit registry was challenged in 1982, after a gay youth-employment counsellor was falsely accused of paying a 15-year-old street kid for oral sex-and put on the child abuser’s registry without his knowledge.

Though the youth admitted the charge was false and retracted it just days after it was made, the counsellor remained on the registry and the government refused to remove him.

He was left jobless. Sentiment amongst the gay community at the time was that the BC government left him on the registry because of his sexual orientation.

The counsellor began a long, brave fight to be removed from the registry and clear his name.

He filed a petition with the BC Supreme Court and in March 1984, days before he was to present his case, the government backed down and removed him from the registry.

As a result of this case, changes were made to the legislation.

The government decided to inform people of their placement on the registry, a hearing was required and those on the list had the right to appeal after they had been on the registry for three years.

But the counsellor’s case had an even larger impact: after continued criticism from BC’s ombudsman and civil liberties groups, the Ministry of Human Resources acknowledged that the registry had little value due to inconsistent, outdated record-keeping from local offices.

The registry was quietly scrapped in the fall of 1984.

“There’s a history in this,” says Dutton. “It’s a bit of a cautionary tale.”

And though he says today’s federal legislation is much tighter, Dutton believes that what happened over 20 years ago could happen again.

Indeed, the threat of misuse was detected earlier this year when Xtra West reported that under Bill C-16 people who participate in consensual, victimless ‘sex crimes’ could potentially end up on the new sex offender registry.

At the time, in early January, the federal agency preparing the list of crimes to be included on the new registry could not rule out the inclusion of sexual offences such as park sex and indecent acts.

But new information suggests the national registry won’t list consensual sex offences-even those still listed in Canada’s Criminal Code, such as public sex, anal sex and indecent acts.

Today’s registry lists two categories of offences: one for offences A, C, D and E, and another containing offences B and F. The crime of an indecent act is a category ‘B’ offence.

Committing any of the offences in the first category (which includes non-consensual crimes such as incest, rape and sexual assault) will automatically get you on the registry.

But if an offence in the latter category is committed, such as an indecent act, it is up to the Crown to prove that you committed it with the intent to commit a sexual crime in the first category. Otherwise the offender won’t be added to the registry.

Given these provisions, gay lawyer Garth Barriere feels that the odds are extraordinarily slim that people who are caught having consensual sex will end up on the registry.

“I don’t see this being particularly problematic for gay men having consensual sex,” he says.

Liberal MP Hedy Fry says that the aim of the registry is to act as a tool to help police search for sexual criminals-not persecute gay sex.

“An act of indecency is not a sex offender. We’re looking for predators,” she says.

The new registry is simply intended to help police find a list of suspects, she repeats.

According to Barriere, sex offender registries do not have to be a strictly negative concept.

“The idea of a sex offender registry on its own is not a bad idea,” he says. “What matters is how it’s written and who is included.”

With the new legislation, the government appears to have taken care to ensure that the wrong people won’t end up on the registry.

However, Barriere feels there is still the question of whether the usefulness of the registry will be justified after the benefits of having one are weighed against the potential violation of privacy to those who have committed sexual crimes.

Fry agrees: “We have to strike a balance.”

The BC government seems to have full faith in the new national registry and is ready to do its part. On Mar 21, it announced the creation of a new permanent police unit called IPSOT to monitor sexual predators who have been released from prison.

But whether the national sex offender registry will actually be useful in catching criminals remains to be seen.

“I think it can show some promise,” says Barriere. “But we’ll need to see down the road.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra