To begin with, what is a Fennel Plunger anyway? This dubious object is the nom de guerre of three media artists: Jean-Paul Kelly, Steve Reinke and Anne Walk, whose latest show, All Rag, No Bone, is up at Mercer Union.

To me, their collective name evokes someone trying to use a bulbous root vegetable to unclog a blocked toilet: a perverse, fecal and ultimately self-defeating enterprise. As it happens, this is a fairly good summary of the ethos of the group. Whatever their path of approach, they all land in the same spot: defeat, cruelty, confusion, mortification. They’re not sadists, by any stretch of the imagination (well, the jury’s still out on Reinke); they see the evidence of these conditions all around them, and they respond with gentle criticism, a shrug of the shoulders and some semiotically charged art.

All Rag, No Bone is a fairly (almost surprisingly) prosaic title, taking an already sad phrase (“rag and bone”) and making it even sadder: the Fennel Plunger Corporation takes a collection of scraps and leavings and reduces them to a limp pile of dejected cloth, with not even the firmness of bones to give it substance. And there you have your central themes: absence, emptiness, impotence.

All Rag, No Bone is an ironic enough title, given that the first thing you see upon entering the gallery is a boner. Well, not a boner exactly: Kelly gives us an exquisitely detailed line drawing of a sheet propped up by a stiff cock. But the dick is covered, and the body to which it should be attached is nowhere to be seen. We don’t quite have a full-blooded erection, just the trace of it. You see? Absence. All rag, no boner.

Kelly takes up the bulk of the wall space with a few other drawings and his sumptuously photographed Rags series — a procession of tarpaulins titled after global newspapers, references to the body bags and other such coverings that hide the corpses left in the aftermath of front-page catastrophe stories. All body bags, no bones.

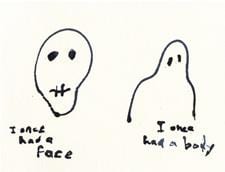

Steve Reinke presents a suite of videos, needlepoints and drawings. The drawings — quick doodles, schematic and puerile — stand in sharp contrast to Kelly’s graceful, neurotic precision. Reinke’s needlepoints are likewise doodles, although on a much more time-consuming, detailed scale. And his videos further flesh out the various cruel perversities of the Reinke universe.

The one that stuck with me was a very calm narration of an apparently popular viral web video, in which a female hunter gets fucked over the carcass of the bear she just shot (Reinke covers the bear with an amorphous blue dot, for “humanity’s sake”).

Anne Walk has two excellent works in the show: one a collection of photographs of an East Coast vacation, introduced to the viewer as a horrible disaster. Of course, the disaster is never represented, its potential trauma looming all the larger for its mysterious absence. The other is a deceptively simple take on an old Warner Brothers cartoon: a down-on-his-luck man tries to market his singing, dancing frog. When it comes time to audition, the frog is mute, and the frantic man pathetically tries to animate it himself. When you enter the second gallery room, you hear Walk’s voice behind a wall, singing “Hello, My Baby.” As you turn the corner, her voice stops, and all you see is a TV on a plinth playing footage of the singing-frog fail. Once you leave, perplexed that that’s all there is to the installation, her voice starts up again.

It’s a neat encapsulation of the thrust of the show: no matter how hard you try, you’ll never get there. All you have is absence, which is nothing at all. It’s to the Fennel Plunger Corporation’s immense credit that a show about defeated nothings is so charming, engaging and winning. They might be telling us there’s no there there, but their delivery makes all the difference.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra