Did you hear the one about the drag queen who wanted only Will & Grace fans to come to trivia night?

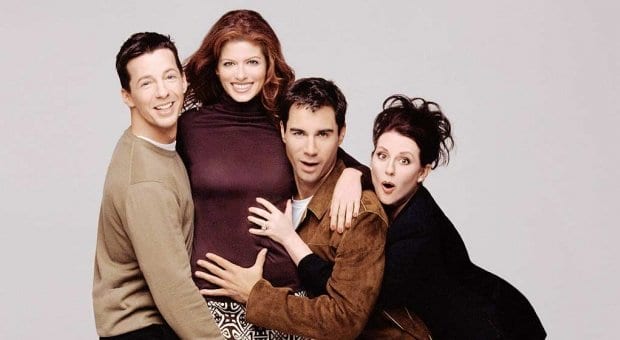

At a gay bar that I frequented in the 1990s, trivia night was hosted by a drag queen whose questions were largely and unrepentantly drawn from Will & Grace. For her, it was such a relief to have a mainstream sitcom about queer people that it was important to pay tribute.

As Xtra Ottawa celebrates its 20th anniversary, sometimes it’s a bit embarrassing to remember the pop culture that meant so much to us back in the day. Of course, not all queer people watched or enjoyed Will & Grace, but LGBT representations in pop culture are significant because they influence how queer people are seen by themselves and heterosexuals alike.

For Florian Grandena, a University of Ottawa professor who studies gender and sexual identities in contemporary cinema and popular culture, Will & Grace was a problematic show because it perpetuated stereotypes — Jack as the shallow, flamboyant gay man and Will as the uptight, domesticated gay male.

“Will was the cliché of the domesticated gay man, but he was never quite portrayed as a gay man as such,” Grandena says. “He seemed to be in a typical heterosexual relationship with Grace. Those two were the real couple of the sitcom. Very rarely was there any tenderness expressed between two men.”

Grandena also objects to queer representation being limited to white, youngish, urban, well-dressed, good-looking men. To this day, there’s a lack of diversity in mainstream queer representation, which renders the underrepresented members of the community virtually invisible, he says.

“The LGBTQ community is a minority, and when you are a minority you are desperate to have models, to have images of yourself,” Grandena says. “Growing up without having a chance of seeing yourself on [TV or film] is not a good thing for your self-esteem, for the construction of your self, especially when you are forced to consume images of another type of identity that is being forced on you as the norm.”

Locally, you don’t have to look far to see queer art, theatre and artists in Ottawa, but there’s hardly room for complacency, says Guy Bérubé, founder and director of La Petite Mort Gallery (LPM).

“The past 20 years were really a struggle for control over representation,” Bérubé says. “And we never have had control; it is always a matter of resistance and education.”

Since 2005, LPM has celebrated diversity by showcasing the work of local, national and international artists who challenge expectations or norms, he says.

In Ottawa’s theatre world, it seems like queer representation has increased over the past two decades — or it might just be that she’s paying closer attention, says actor/director Margo MacDonald, an Ottawa native.

“I personally have tried to provide more [queer representation] in the work that I’ve been doing,” she says. “I’ve got three or four shows in [this] season that all have queer content. To me, that’s a very happy thing.”

In the 1990s, Ottawans saw plays with queer content like Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes, Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize–winning play about politics, religion and AIDS, which ran at the National Arts Centre. Bryden MacDonald’s Divinity Bash/nine lives, which featured a trans character and explored issues of identity and alienation, also ran at the NAC.

By the early 2000s, Ottawa had queer theatre company Act Out, which dissolved in 2005 in the midst of financial debt. In 2007, TotoToo was formed, producing excellent dramas and comedies over the years. Its team recently launched its 2013/2014 season during Capital Pride after being on hiatus for one season due to planning difficulties.

Whether it’s produced in Ottawa, Hollywood or elsewhere, when you consume TV, film, theatre, comedy, visual art and the written word, it’s important to recognize that pop culture doesn’t render you a passive observer, Bérubé says.

“It is our right and responsibility to challenge representations,” he says. “As simple as it sounds, the trick is letting everyone know they can be a part of this thing called art. Seeing exhibitions or artworks and supporting the careers of artists mean that these discussions will live on.”

Grandena agrees, saying when we object to stereotypical portrayals of queer people and women or are concerned by the lack of diversity in TV’s queer characters, it’s important to let our concerns be heard.

While MacDonald loved The L Word and these days enjoys Orange Is the New Black, she says ultimately, the queer artists in her own community inspire her the most.

“I was always very aware — like heightened awareness — of the other queer artists who were working in the city and how they were able to sometimes bring a queer perspective to things,” she says. “That’s still really important to me today — to be out and doing work that represents the community.”

More on Xtra Ottawa‘s 20th anniversary:

Memoirs of an Art Fag — this ’90s scenester column tackled politics and culture

20 years of shining the light: Practising community journalism is vital, but it’s a difficult task

Our spaces, September 1993 — a look back at where Ottawa’s gay community gathered 20 years ago

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra