An enormous slug fills its human lover’s mouth, nose and vagina with its slimy undulating body. She spreads her legs, letting the slug push itself further inside of her, orgasming as it thrusts.

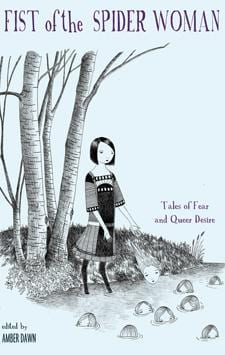

The slug in question is the title character of Megan Milks’ story in Fist of the Spider Woman, an anthology exploring the relationship between terror and longing.

“We do have some of our most frightening, challenging moments in close juxtaposition to maybe some of our hottest moments, to maybe our moments where we had awakenings about desire,” says Amber Dawn, the book’s editor.

As a pre-teen, Amber Dawn encountered this juxtaposition when reading the forbidden books she snuck off the grown-ups’ shelves, including The Amityville Horror and Story of O.

Later, she dealt with the fear of being bullied that surrounds being a queer teen, which motivated her to volunteer at rape crisis centres and to ally herself with women who had fear thrust upon them from traumatic experiences.

“I’ve been a fighter of fear for a long time. Somewhere in that fight, fear started snuggling up next to desire,” Amber Dawn explains. Playing with fear in the bedroom was an empowering experience, and it led to the idea of a horror anthology.

“This conversation about fear that’s taking place in Fist of the Spider Woman feels very triumphant to me, it feels like a victory, as opposed to a debriefing of some sort of hardship or trauma. So I wanted to [put the anthology together] for myself, but I also wanted to put something out there where fear was explored in a very brave, and also feminist way.”

Fist’s 16 stories and poems range from the popular lesbian vampire motif in Fionna Zedde’s “Every Dark Desire” to Michelle Tea’s autobiographical “Crabby,” which describes her almost comical encounter with pubic lice. But the most engaging stories are those that manipulate the horror genre to construct an elevated understanding of the queer experience.

In “In Circles,” Aurelia T Evans introduces her readers to Kate, an intersex woman whose recently renewed discomfort with her body makes her long for the mutilation offered by Bloody Mary, who begins appearing in her bathroom mirror.

The story confronts the connection between mutilation and genital corrective surgery and how undergoing the surgery suggests a death of the self. It is a formidable look at a subject rarely touched upon and offers a unique take on the fear-desire relationship.

“I’d always thought of fear and desire as two very separate emotions, two very separate motivations, and Amber Dawn’s call for submissions was a challenge,” reveals Mette Bach, whose contribution, “All You Can Be” takes place in a military hospital where a sinister doctor injects her paralytic, enamored and unwitting patient with an unknown substance.

After 12 attempts at writing stories with supernatural elements, Bach concluded that ghosts and monsters weren’t actually frightening. “What I’m scared of is cruelty that’s unclear. Cruelty that’s masqueraded as kindness or love,” she explains, “like when we fall in love with someone, how do we know that we can trust them? We don’t. In fact, we’re even more vulnerable than with someone with whom we don’t love.”

The notion that love makes us vulnerable to mistreatment is carried on in Kestrel Barnes’ “Shark.” Told from a child’s perspective, the narrator tells us about her mother’s death and how years later, her other dyke parent, Baba, brings home a stiletto-wearing evil stepmother, the shark. For Barnes, the community’s response to gaybashings may be adequate, but its willingness to acknowledge same-sex domestic abuse is not.

The element of desire in “Shark” is not related to sex, but rather to safety. When asked about her use of the leather jacket as a symbol for safety, Barnes points to her own experience of motorcycle accidents and being bashed and how her leather jacket lessened her injuries.

She also points to her children’s comfort relationship to her leather. “When they were small, every single one of them, I would zip into my leather jacket, they’d teethe on my collar. If I’m not home at night and one of the babies is fussy, one of the older kids will wrap them up in one of my leather jackets. So yeah, for us, it’s something really concrete. Leather protects us. Leather is part of our family. It’s part of our home,” Barnes says.

Home was a subject Amber Dawn had in mind when writing “Here Lies the Last Lesbian Rental in East Vancouver.”

In it, Trinket and Zoya are spending their last night in their rented house playing “mean mommy” and hide and seek, when the blindfolded Trinket is assaulted by a lesbian poltergeist whose sexuality was repressed by her Italian Catholic background and the time period she lived in.

Weaved throughout the story is the house’s history of queer tenants and their activism, which gives voice to the fear of gentrification.

“If I lost my apartment right now, that would be the most terrifying thing that could happen to me,” Amber Dawn confides. “Anytime I’m at a party where there’s a whole bunch of queer women they’re always like ‘oh, my house went up for sale.’ And I feel like it really fucks up our community.”

Whether you fear gentrification, cruelty, slugs or something in between (or all of the above), Fist of the Spider Woman examines our fears and taboos and asks how they relate to our longings. Then it offers thigh-clenching grotesque to a readership longing to see itself represented.

“Our imaginations, when it comes to both fear and desire, are really limitless,” says Amber Dawn. “And I can guarantee that when this book starts to be blogged about or discussed amongst friends or wherever it’s being talked about, other people are going to say, ‘Yeah, I’ve had slug fantasies too.’ Like Megan Milks is certainly not the only one to explore sex with a slug. It’s somewhere else in someone’s mind…

“It wouldn’t surprise me if someone posted a link on my Facebook wall in a couple months from now that was like, slug porn,” she laughs.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra