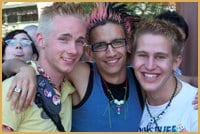

FIREFLIES ONE AND ALL: Carl (clockwise from back left), Isaac, Pat, Leonardo, Murray Billett, Desmond, Margo and Bart. Credit: (Photo courtesy of Kris Wells)

Leonardo, a young man with a shock of pink in his otherwise dark hair, smiles as he surveys the energy and bustle of his first day of camp. This is “amazing,” he says. “I am really, really happy to be here.

“I was not expecting a camp like this, because my only other camp experience was one that was basically for straight people. Here, I do not have any fears. I can be myself–just be Leonardo. Meeting all of these people, and everyone sharing a little bit of their lives, makes me happy.”

Originally from Mexico, Leonardo (who, like Camp Fyrefly’s other youth, only offered his first name for publication) is now active in Toronto’s queer community. He works with an organization that supports queer youth in such areas as sports and recreation, arts and culture, employment, mentoring and housing.

“The camp is making us more confident,” he says. “All of the things we are learning here–being yourself, being able to express your true feelings, not being afraid to be gay–we can take back home to the other youth who are working in our communities.”

Now in its third year, Camp Fyrefly is a queer leadership camp for young people aged 14-24. It’s the only one of its kind in Canada. This year, participants came from across the country to attend the four-day session held in Edmonton, Jul 6-9.

“The firefly is one of the only animals that produces its own energy, which I think is a poignant symbol for the camp,” says Kris Wells, the camp’s director and co-founder. “We want to move youth from feeling at risk to feeling resilient in their communities, so that their own light can glow in dark times.”

The camp begins, as in any gathering of people who do not know each other, with people triangulating, looking for friendly faces, seeking level ground. However, with young people this process is accelerated and the furtive glances are soon met with smiling faces.

Several conversations break out as campers haul pillows, sleeping bags and luggage into the courtyard of the Bennett Centre, an outdoor education and conference centre operated by the Edmonton Public School Board.

Rainbow accoutrements are obviously de rigueur, with bracelets, badges and pins everywhere on display. There is a decidedly out subtext, and an excited, expectant atmosphere.

Lindsay, a young woman from Red Deer with glasses and a wry sense of humour, is reconnecting with several friends. “This is my second year in a row attending the camp. There aren’t many places to go in Red Deer for gay people,” she notes with an arched eyebrow.

As the campers get settled in their mixed-gender cabins, their pod leaders arrive to introduce themselves. As the main unit of organization and affiliation at the camp, pod members gather a few times a day to work on pod activities and tackle group chores.

All of the pod leaders are youths themselves, only slightly older than their charges, who participated in the camp last year or the year before and liked it so much they wanted to come back–albeit in a more official capacity.

One thing the pod leaders stress is the importance of mixing with everyone, as opposed to simply pairing off. In fact, the camp has a strict anti-hanky-panky rule, enforced by a designated hanky-panky police person.

Despite the organizers’ attempt at temperance, an underground anti-anti-hanky-panky culture thrives among the campers.

Love and hormones aside, one of the main challenges at Camp Fyrefly is choosing among the impressive smorgasbord of workshops that are on offer. Campers can attend workshops on sexuality and spirituality, DIY zine creation, using theatre to address world issues, safely addressing homophobia and heterosexism–there’s even a seminar on Reiki.

The camp also brings in a few high-profile members of Edmonton’s queer community for discussions with the youth.

One such session, entitled “Out in the Police Force,” stars Edmonton police Sgt Danielle Campbell.

“I am just awestruck that we are in a day where we can have a camp for youth who are gay or bisexual or transgender,” she tells the youth. “I think it is a wonderful.

“In high school I thought I was the only lesbian in Canada,” she continues. “I wish I had a camp like this when I was younger. I would have been there.”

“I was impressed with Sgt Campbell’s talk,” Margot later says, in between bites of her sandwich.

Margot, a Grade 12 student at a local Edmonton high school, says she doesn’t feel discriminated against at school. “I would have no problem holding hands with my girlfriend in the hallways,” she says, though she notes that kissing is a public no-no for everybody, regardless of their orientation.

Isaac, a Grade 10 student from a different high school across town, is out at school too, but he doesn’t think he would get away with holding a boyfriend’s hand unscathed.

“I am actively involved in my school’s gay-straight alliance but there are places in my school where I don’t go because I could get into trouble,” he explains.

Other youth soon chime in around the lunch table, and the discussion quickly becomes a debate on whether lesbian students have an easier time in high school than their gay male counterparts. They conclude that the girls have it easier–but just barely.

The next day, about 50 queer youth gather to do warm-up stretches in the post-mosquito morning.

The crowd is peppered with the lime green Camp Fyrefly T-shirts the organizers gave the participants when they checked in. Those who don’t want to stretch, or who simply aren’t morning people, sit in small conversations nearby.

One of the most unexpected things at this gay youth camp is the distinct feeling that sexual orientation and gender have ceased to matter. As a result of everyone presenting their queerness explicitly, the issue–which seems such a core part of most queer people’s identities–almost evaporates. It is a sneakily vertiginous experience where queer becomes the new normal.

“The surprise about this camp is how normal it really is,” agrees QC Gu, one of the youth coordinators who helped design this year’s activities. “The camp is just a leadership camp–kids coming together having fun.

“The other surprise is the adults who come to this camp grow just as much as the youth,” he adds.

“We had 25 adults apply for our adult leader positions before we received our first youth application,” says camp coordinator Jill Delarue. The adult leaders teach workshops and bring their professional skills to the camp, all of which are donated, including their sacrificed holidays.

“Knowing that a camp like this exists touches a chord in people,” observes University of Alberta professor Andre Grace, Camp Fyrefly’s über-mentor and co-founder (and unofficial father figure).

“We have had tremendous support from the LGBTQ community in funding the camp,” Grace adds.

This year, Camp Fyrefly managed to stretch its resources to offer spots to 55 youth (and 12 adult leaders). They had originally advertised 50 spots. Despite the extra five spaces, the camp still had to turn 12 youth away.

“As the camp continues to grow, I think about the other dozen who did not have a place,” says Wells. “My future hope is that camp funding will increase so more youth can attend.

“We currently run the camp as cheaply as we can so that we can get as many youth to attend as possible,” he notes. “Those who could not attend this year we will put on top of the list for next year.”

One source of current funding, and potentially more funding in the future, is Edmonton’s own city council.

“There have been a lot of changes in the city of Edmonton over the past 15 years,” says gay councillor Michael Phair. “We really support community initiatives such as this camp. This year, the mayor hosted a Pride brunch during our Pride Week celebrations and all of the proceeds went to support Camp Fyrefly.”

Grace hopes Camp Fyrefly spin-offs will someday dot the horizon. “I would love that,” he says. “We have been very careful to document everything that has been done in the last three years, and we have these resources to share with anyone who is interested.

“There should be one of these camps in every province and territory in Canada,” he concludes.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra