If you want to know what the Tea Party’s version of America will look like, pick up R Tripp Evans’s Grant Wood: A Life.

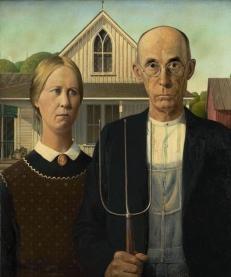

Wood is best known for painting American Gothic, which has long served as a logo for heartland values and small-town life. Recently, a lobbying group wanted to change the name of the Defense of Marriage Act to the American Gothic Act.

Tripp takes great pleasure in suggesting that Wood was not only a homosexual, but that he didn’t go to church and that the woman in the painting was 35 years younger than her male companion.

He is also keen to point out that people generally walk away from the famous painting feeling disturbed.

Not much has changed since Wood’s days, during the Great Depression. Urbanites thought the Bible Belt was “Babbity” and the Bible Belt thought urbanites were elitist. Wood and his artist friends in Iowa sought comfort from their repressed lives in HL Mencken’s — the Jon Stewart of their time — syndicated column.

Besides his apparently arrested development and his co-dependent relationship with his sister and mother, what’s fascinating about Wood is how he, as an effeminate man, was able to navigate the narrow definition of masculinity that prevailed in his time.

After the Civil War, boys were encouraged to be tough and rugged. Any sort of art or creative writing was discouraged. Wood himself was named after Ulysses S Grant, the Union Army’s military commander. As a boy, Wood drew only after his father left for the fields. A great sense of shame was attached to his art when he started painting.

Still, Wood managed to be a stylish and handsome adolescent and made a living as an interior decorator and set designer. He even parlayed his talent to the military during the First World War as a camouflage painter.

Tripp alludes to a number of relationships Wood had with both married men and protégés, but for the most part they come off as non-sexual infatuations.

Wood’s yearly painting excursions to Paris would also imply some sort of sexual activity, but there’s no smoking gun. There is never a sense that Wood had a sexual awakening of any sort. Instead he used his mother as a sexual shield, claiming that caring for her prevented him from entering into a serious relationship with a woman.

Wood experienced a transformation in art and style after a visit to Munich. On his return to America, he wore nothing but farmers’ overalls and went from being an impressionist painter to a regionalist. He painted American Gothic within the year.

To Tripp, the best evidence of Wood’s sexuality lay in his paintings Arnold Comes of Age and Dinner for Threshers. His conclusion: Wood must have been an ass-man given the amount of detail he put into them.

Tripp has less success imposing Wood’s sexuality into his landscapes. It doesn’t take an art critic to know when someone is reaching.

Whatever Wood did between the sheets, he embraced his role as an icon of the heartland and did not hesitate to hint that something was gay if it helped his career. Whether or not Wood was a traitor to his kind or working covertly to subvert his oppressors is, like his body of work, in the eye of the beholder.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra